The Arithmetic of Life and Death (3 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

Relative to the number of CEO jobs at Joe Bob’s company, that’s a fairly big safety net. It could improve Joe Bob’s chances of “executive suite” success to perhaps 1 in 11—if he gets the M.B.A., if he has the talent, if he works hard, and if he can accept a definition of success that is something less than the pinnacle.

“Alice’s Restaurant” is not real life. You can’t be anything you want. It’s not a right guaranteed by the Constitution. But if you aspire to something extraordinary, you do have a better opportunity in today’s United States than in any other nation on Earth at any time in history.

3

The Value of Education

How to Earn $200 per Hour in High School

“Educated men are as superior to uneducated men as the living are to the dead.”

— ARISTOTLE

E

very year, thousands of bored, underperforming, or disenfranchised teenagers drop out of high school prior to graduation, even in the idyllic Northwest. Billy Ray DeNiall, who at age sixteen is not at all like his ambitious older brother, decided to quit school at the conclusion of his sophomore year. Like most conscientious parents, his father vehemently disagreed, which instantly resulted in the usual shouting match.

After the elder and junior DeNialls managed to calm down, Billy Ray agreed to go to the library and check out the 1996 publication of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. In it, he discovered that college graduates earned an average of $719 per week, high school graduates earned an average of about $450 per

week, and those who did not complete high school earned about $318 per week.

Therefore, ignoring inflation, an average college graduate will earn about $1.495 million over a forty-year career. High school graduates can work longer. Over a forty-four year career, they should average $1.03 million dollars in earnings, some 31 percent less than college graduates. Those who don’t complete high school should work for about forty-six years and will earn just under $760,000 on average, 26 percent less than high school graduates and 49 percent less than college graduates.

Graduates make a lot more money. But there is a price: all that extra school.

Billy Ray needs two more years to get his high school diploma. At 180 days per school year and a diligent eight hours per day including study time, that is a total investment of 2,880 hours. If Billy Ray becomes an average wage earner, he will make about $270,000 ($1.03 million minus $.76 million) more as a high school graduate than he will if he drops out. That is a return of $135,000 for each of his last two years of high school, or more than $93 for every additional hour of class and homework ($135,000 ÷ 180 × 8).

Using the same assumptions of eight working hours per day and 180 days per school year, the cost of college is another 720 days or 5,760 hours of hitting the books. The return, however, is an additional $466,000, about $116,500 per year, or more than $80 per hour of college—and more than fifteen times minimum wage.

However, these figures presume no inflation, which

is implausible as long as there is a Congress.

*

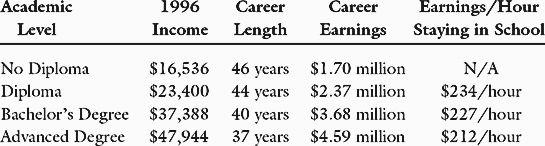

Assuming that the starting salary is one half the career average in each category and inflation is 5 percent from 1997, then career earnings for the year 2005 college graduate will be around $3.68 million for forty years of work, $2.37 million for the year 2001 high school graduate over forty-four years, and $1.7 million for the high school dropout over a forty-six-year career that starts on the first day of the year 2000. (For those of you keeping score, the model assumes that each graduate begins work on January 1 of the year after graduation.)

This means that Billy Ray’s extra two years to finish high school are likely to be worth about $675,000, or about $337,000 per year and $234 per hour—which is more than some lawyers make! If he can keep his focus for another four years of college, his bachelor’s degree should be worth another $1.31 million, or more than $325,000 per year. Try making that kind of dough at the local pizza franchise.

Graduate school (a master’s degree or a Ph.D.) is also financially attractive. In 1996, people with advanced degrees averaged nearly $48,000 per year. Equalized against the other examples, a graduate with an advanced degree will earn about $1.77 million in 1996 dollars over a thirty-seven-year career and about $4.59 million assuming 5 percent inflation.

The four levels of academic achievement compare economically as follows:

Money isn’t everything, but, like knowledge, having more of it is demonstrably superior to having less of it. The highest paying job most folks will ever have, Billy Ray included, is school: more knowledge; more money; win-win. Therefore, the only intelligent decision is to stay in school until graduation. Any other course is too likely to lead to a lifelong, low-budget search for what might have been.

Less knowledge equals less money and lower self-esteem. Lose-lose-lose.

*

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the last full year in which there was no U.S. inflation was 1954 during the Eisenhower administration. The last time there were two consecutive years of no inflation was 1938 and 1939 under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Since 1954, there have been 44 consecutive years of inflation.

4

The Sum of All Decisions

“When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

—YOGI BERRA

G

wendolyn Sharpe, daughter of Cecilia, never had any doubts about whether she would go to college. From an early age, she knew she would. But as graduation from high school approached, and as the pressure to decide mounted, the question of which college to attend became more and more difficult.

Like many ambitious high school students, Gwendolyn had applied to a large number of universities. In fact, she had applied to twelve, all highly regarded. Because she was an excellent student with very good S.A.T. scores and because she required no financial aid, she had been accepted by nine of them. After a lot of research, hours of debate with her friends, and several consultations with her school counselor, she had managed to narrow the field of candidates to five.

But now, in the final days of her high school career, a decision was overdue. Yet Gwendolyn, who intended to major in anthropology, felt paralyzed because there was no clear winner: The best academic university was also the most expensive, the college with the best school of anthropology was the second-most expensive, the university with the best overseas research program was in the middle of a large and expensive northeastern city, the university closest to home had a weak anthropology program, and the least expensive choice was a small school in a small town with nonexistent prospects for employment.

As Gwendolyn’s deadline approached, she found she had no alternative but to ask her mother for assistance. Cecilia, in turn, managed to stifle her surprise and immediately agreed to help. Once they had cleared away the dinner dishes that night, the two of them sat down to see if they could resolve the dilemma. First, Cecilia listened to Gwendolyn’s analysis of the situation at length, which was an excellent example of proper teen parenting. Then she went into the kitchen to fix the two of them a cup of coffee. In the meantime, she asked Gwendolyn to get a few pages of graph paper and a pencil. Gwen was puzzled, but since she was also suffering from digestion-induced oxygen deprivation in the brain, she decided not to question her mother this one time.

When they got back together at the table, Cecilia took charge of the pencil and paper and asked Gwen to list what was important to her in the selection of the right university. After lengthy discussion and an idea or two from Cecilia, Gwen agreed that the most important selection criteria were: university reputation, quality of the anthropology curriculum, future employment prospects, tuition

cost (one of Cecilia’s suggestions), living costs (another from Cecilia), opportunity for postgraduate work, quality of student life, closeness to home, and quality of student living facilities.

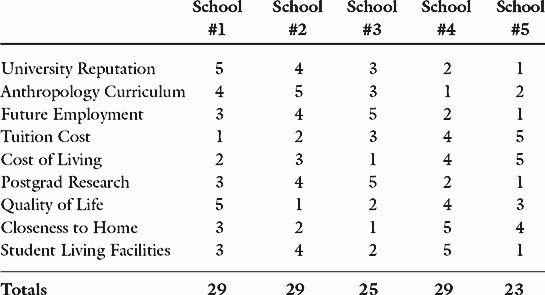

Next, Cecilia asked Gwendolyn to rank each of the five universities, one criterion at a time, with five being the best score and one being the worst. After a lot more discussion, and no small amount of reconsideration and alteration, Cecilia was able to produce a simple table of Gwendolyn’s rankings:

Gwendolyn and Cecilia were both happy to have such a clear picture of the situation, but given the lateness of the hour, both were also disappointed that three universities were still in the running. So Cecilia suggested that Gwendolyn apply a weighting factor to the remaining three universities that would tend to emphasize the most important criteria and de-emphasize the least important. After some

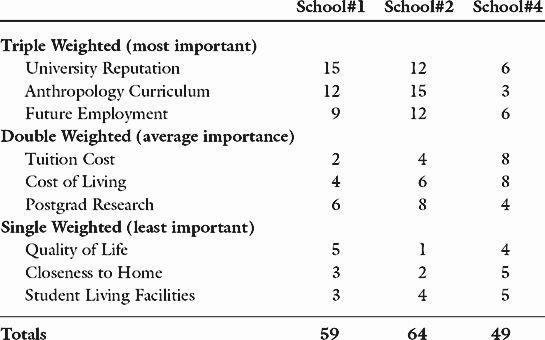

discussion, they agreed to multiply the most important three criteria by a factor of three and the next three most important criteria by a factor of two. While Gwendolyn watched hopefully, Cecilia produced the following result (with five still being the highest score before weighting):