The Arithmetic of Life and Death (7 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

Faced with an unknown quantity of randomly arriving work, most people resort to one of three methods of work organization:

- They attempt to complete each task in the order it arrives (called FIFO in industry argot, which means first in, first out).

- In order to minimize the number of tasks left in the

“In” basket at the end of the day, they do the easiest ones first. - Because the hardest tasks are the most difficult to predict and complete, they get them out of the way first.

Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, and each produces a different result.

Coincidentally, Cecilia Sharpe encountered exactly those three methods of organizational behavior when she was consulting at a local bookkeeping firm. In order to determine which of the three methods was most productive, she created a series of eight tasks, each with a different degree of difficulty and varying economic value to the firm, as follows:

| Order of Arrival | Time to Complete | Billable Value |

| 1) | 90 minutes | $120 |

| 2) | 120 minutes | $150 |

| 3) | 15 minutes | $25 |

| 4) | 60 minutes | $50 |

| 5) | 30 minutes | $100 |

| 6) | 105 minutes | $200 |

| 7) | 75 minutes | $180 |

| 8) | 45 minutes | $75 |

| Totals | 540 minutes | $900 |

To simulate real-world behavior, Cecilia put all eight tasks, which were unrelated to each other, on the desk of each of three bookkeepers at the beginning of the workday. She told each of them that any uncompleted task was not billable and therefore would not contribute to the day’s

productivity. Finally, she told each of the bookkeepers that they had only five hours to complete as much work as possible because a two o’clock meeting had been scheduled in the controller’s office to discuss travel policy, which would take up the rest of the day.

Well aware that a nine-hour workload for a five-hour day was typical of their company’s management style (see

chapter 18

), the three bookkeepers approached their tasks with stoic resolve and their usual methodology:

- The first bookkeeper performed each task in order of arrival. After five hours, she had completed tasks 1 through 4 and was halfway done with the fifth. Since work-in-progress was not billable, her daily contribution to the firm was $345.

- The second bookkeeper, a small, black-haired, spark plug of a woman named Helga, always wanted to complete as many tasks as possible. As a result, she finished five tasks: numbers 3, 5, 8, 4, and 7. She also managed to complete 83 percent of task number 1, but it didn’t count. Her total contribution to the firm was $430.

- The third bookkeeper attacked each task in the order of difficulty (greatest to least), finishing only tasks 2 and 6. His total productivity was $350.

It appeared to Cecilia, and to her client’s controller, that the method of doing the most tasks was best. But the next day, just to make sure, Cecilia reversed the order of arriving tasks and asked the first bookkeeper to repeat the test. Taking each task in order of arrival, she managed to complete numbers 8, 7, 6, and 5, producing a total of $555 in billable

revenue. This proved to be a substantial victory for her method and a point of some embarrassment for Cecilia, Helga, and the local management team.

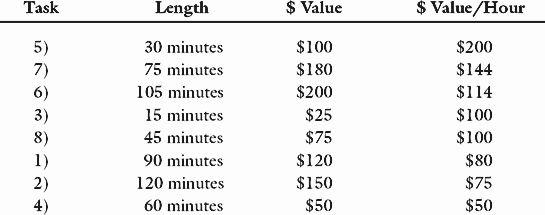

Cecilia, however, was undeterred. She went home that evening, sat down with her Sharp (no relation) calculator, and reanalyzed the problem. The solution began to come clear when she restructured the task list as follows, by equalizing all tasks to value per hour:

Cecilia returned to work the next day and asked Helga, the second bookkeeper, to perform the tasks in the order of productivity, meaning highest value per hour. After five hours, Helga had completed tasks 5, 7, 6, 3, and 8 for total billable productivity of $580, which was 4.3 percent to 68 percent more productive than every other method that had been tried. And she had an extra thirty minutes left over to help the controller write up the new travel policy.

Having solved the problem to management’s satisfaction, Cecilia moved on to her next consulting assignment. But when she returned a few months later for the annual audit, she was surprised by what she found. Despite the best efforts of the controller, the first and third bookkeepers

had persisted in their simple but suboptimal ways. Helga, however, had adapted her work behavior by prioritizing her projects based on value. As a result, she had received a promotion to cost accountant, a merit raise, her own office with real wood furniture, and the veiled antipathies of the two bookkeepers left behind in the catacomb of cubicles at the other end of the hall.

During the audit, Cecilia and Helga had plenty of time to chat. Over the course of their conversations, they both agreed that they had learned three things:

- In today’s business world, the amount of work always exceeds the amount of time available to get it done.

- Those who prioritize by value to the business will be most successful.

- Despite the obvious benefits of value-based prioritization, most workers will persist in completing tasks by order of arrival or degree of difficulty.

In the end, Helga and Cecilia both concluded that this state of affairs, although counterintuitive and backward, was an opportunity for those willing to adapt, to focus, and to prioritize. They also agreed to tell only their close friends and coworkers.

11

Rules of Thumb

“Any excuse will serve a tyrant.”

—AESOP

I

n life, there seem to be a lot of “Rules of Thumb.” In general, Rules of Thumb are guidelines people invent to explain phenomena that they can’t prove. If these rules seem to work, then other people use them and they eventually become widespread, perhaps too much so. One of the more popular Rules of Thumb is the “80/20 Rule,” which is very arithmetic and which suggests, for instance, that 20 percent of teenagers will get 80 percent of the tattoos, or that 20 percent of your guests will drink 80 percent of your wine, or that 20 percent of your customers will be responsible for 80 percent of your business.

When Cecilia Sharpe first joined the accounting firm where she still works to this day, she noticed that there was an enormous gap between the salaries of a few of the firm’s top employees and the rest of the staff. So Cecilia, who was

responsible for the company payroll, approached the managing partner on the issue. That is when she discovered that he was a devotee of the 80/20 Rule of Thumb. More specifically, he ascribed to the theory that 20 percent of his employees produced 80 percent of the company’s results and that, therefore, a geometric gap in salaries was more than justified.

Intuitively, Cecilia had a hard time accepting such a large disparity in either pay or performance among peers. In order to explain her intestinal discomfort to both herself and the boss, she created a simple “cotton picking” model:

- Suppose that ten cotton pickers picked 100 bales of cotton;

- Then, according to the 80/20 Rule, the top two pickers picked eighty bales of cotton; and

- The bottom eight pickers picked only twenty bales of cotton.

- So the top two pickers produced an average of forty bales each; but

- The bottom eight pickers produced an average of only 2.5 bales each;

- Which means that the top two pickers were sixteen times as productive as the bottom eight pickers (40 ÷ 2.5)!

Although impressed with Cecilia’s imagination, the managing partner remained unmoved. To make his point, he wagered one dollar that Cecilia would find that the 80/20 Rule was, in fact, a reasonable reflection of real-world employee productivity.

Cecilia accepted the wager. However, since companies

that measure productivity tend to keep their results confidential, she had a difficult time finding a general but statistically rich business model in which individual productivity could be analyzed within a framework of overall performance.

After more discussion with the managing partner, Cecilia finally agreed that professional sports, which were statistically rich at both the individual and team level, would provide a fair and reasonable basis for their test. That very Sunday, while surfing the Net, she came across the 1997/1998 statistics for the now defunct Seattle Reign professional basketball team. The eleven scorers for the Reign that season were:

Player

Total points

Enis 754 Whiting 645 Starbird 557 Paye 300 Aycock 269 Ndiaye 195 Holmes 195 Smith 93 Godby 73 Hedgpeth 85 Orr 89

Total3,255

If the 80/20 Rule was correct, Cecilia should have been able to predict that the top two scorers, Shalonda Enis and Val Whiting, who composed 18.2 percent of the team’s personnel, would have produced nearly 80 percent of the

points. However, they scored only 1,399 points, which was just 43 percent of team production. When Cecilia added in the production of the number-three scorer, Kate Starbird, then 27.3 percent of the players produced a little more than 60 percent (1,956 or 60.1 percent) of the team’s point total for the year.

Even though the Reign’s results were far removed from 80/20, there still seemed to be a large gap in personal productivity. In addition, Cecilia was certain that her boss would not accept the results from a women’s team, even if the sports model was his idea. So she logged on to her favorite Internet portal and searched out the 1997/1998 statistics for the Seattle Supersonics basketball team. That year, their fifteen players scored as follows:

Player

Total Points

Baker 1,574 Payton 1,571 Schrempf 1,232 Ellis 932 Hawkins 862 Perkins 580 Kersey 234 Anthony 419 Williams 298 McMillan 62 McIlvaine 247 Cotton 24 Wingate 150 Zidek 29 Howard 25

Total8,239

The top 20 percent of the Supersonic’s scorers, who were Vin Baker, Gary Payton, and Detlef Schrempf, produced 53.1 percent (4,377) of the points. In comparison, the top five scorers, who were 33.3 percent of the team, were responsible for 74.9 percent of the team’s total point production.