The Arrogance of Power (45 page)

Read The Arrogance of Power Online

Authors: Anthony Summers

One day in autumn 1972, at the end of Nixon's first term, one of Jaffe's key operatives, fifty-one-year-old Norman Casper, gained access to a suspect financial institution in Nassau. Casper was an experienced informant, known in the IRS at the time as TW-24, “TW” for Tradewinds. The financial institution in question was Castle Bank and Trust Company, on Frederick Street.

Castle Bank had come under suspicion because a narcotics violator was using it to hide money. Cash deposits had been flowing into a Miami bank without any name identification, then on into Castle's closed vault in the Bahamas. IRS headquarters wanted a list of the bank's other account holders, a tall order indeed. Informant TW-24, however, delivered.

Thanks to a cunning use of his contacts and a pretext that hid his IRS connection, Casper found himself ushered into a small conference room at the bank and left alone to peruse documents related to his ostensible request. He scanned the shelves not very hopefully in search of his real target, and then, right at his feet beneath a pile of folders, he spotted a “brand-new IBM print-out of customers' names, approximately four inches thick, perforated and folded over as it comes out of the machine. I looked at the door, and it was closed. . . . I reached down and leafed through it.”

Worried that a bank official might come in any moment, Casper ran his eye down the hundreds of names on the list. Many of them were companies. Others, like that of Las Vegas racketeer Moe Dalitz, were known criminals. Then came a total shock. “One of the first names I saw,” Casper recalled, “was

the name of Richard Nixon. . . . Lo and behold! That name kind of took the wind out of my sails. When that happened, I think I sat there, got a little bit quiet. . . .” The entry was troubling not least because it was complete with middle initialâ“Richard M. Nixon,” as well as an account number.

Casper reported the discovery verbally to his employer, agent Jaffe, and the wider investigation continued. Jaffe now wanted a copy of the full customers' list, and soonâby dint of a cloak-and-dagger trick that involved separating a bank official from his briefcase while he dined with an attractive womanâCasper managed that too. The document was photographed, page by page, by IRS agents.

There were more than three hundred names on that copy and on another that surfaced later. They included

Playboy

publisher Hugh Hefner,

Penthouse'

s Bob Guccione, the actor Tony Curtis, members of the rock group Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Leonard Hall, former chairman of the Republican party and long a Nixon intimate. Of “Richard M. Nixon” himself, however, there was no longer any trace.

An internal IRS report suggested that since the initial sighting, the entry had been “purged from the Castle records or otherwise concealed.” The probe established that at various stages records were indeed transferred or shredded. As Casper observed, it was surely madness for Nixon's name to have been openly listed in the first place. With Watergate making news in the months after Casper's penetration of the records, to remove it would have been an obvious precaution.

The story did briefly surface publicly much later, well after Nixon's resignation and then only in an oblique sort of way.

24

When it did, the Castle Bank manager, faced with indictments and extradition proceedings, said it was “unlikely . . . in fact, impossible” that Nixon's name had been on the list the IRS had obtained. (No one, of course, had ever claimed that it had been.) The former president of the bank, which lost its license and closed in 1977, tried another tack in an interview with the author. “I am absolutely positive,” Samuel Pierson said, “that the Nixon the idiot read about was a black Bahamian.”

That intriguing notion does not stand up to scrutiny. The name Nixon is not uncommon in the Bahamas, but thorough research involving old voters' lists, telephone directories, and personal interviews has turned up no Richard M. Nixon.

25

Bahamian citizens, moreover, were prohibited by law from holding accounts in offshore institutions like Castle Bank.

A 1972 article in a Nassau newspaper confirms that as the IRS operative recalled, Castle Bank was transferring its records to a new computer at the very time Casper spotted the Nixon name and account number. The man responsible for that process, a Canadian named Alan Bickerton, said in 1997 that he had been aware of the identity of all the bank's customers. Asked if one of them had been

the

Nixon, however, he declined to answer. “I'm not prepared to discuss it at all,” he said. “It wouldn't matter if it were Richard Nixon or the prime minister of Canada. I wouldn't discuss it with you. . . .”

Never satisfactorily resolved, the matter was lost in a troubling upheaval within the IRS.

26

Higher-ups suspended the Jaffe probe, blowing its cover in the process. There was a protracted internal row, with dark hints about the fact that IRS Commissioner Donald Alexander was a Nixon appointee and that his old law firm's name appeared on an index card at the Castle Bank office. Alexander denounced such attacks as the smear tactics of “faceless liars.”

A final odd twist is the reaction of the man who stumbled upon Nixon's name in the first place, and his experiences afterward. Far from trumpeting his discovery when testifying to a House committee probing IRS practices, former informant Norman Casper ventured the opinion that the name might have gotten onto the list because someone “had too many martinis . . . got to playing.” The explanation is implausible but should be interpreted in the context of the fact that the printout especially disturbed Casper because, he told members of the committee, “neighbors of mine were involved.”

What he meant by “neighbors” emerged in a 1996 conversation with the author, as Casper, a decent man highly respected by his IRS colleagues, gradually relaxed his guard. His full story is filled with ironies. A resident of Key Biscayne long before he became an IRS operative, Casper knew Nixon and Rebozo personally. He had met Nixon when he came to stay at the Key Biscayne Hotel, and the Nixon girls had even looked after Casper's daughters at the beach. He had met Pat Nixon and admired her greatly. Casper was in fact a conservative Republican, active enough at one point to have served on the local Republican committee.

Casper likewise characterized Rebozo as “a pretty good friend.” The men had met in the early fifties, and Casper had even run background checks on prospective employees of the Key Biscayne Bank. He had worked for Rebozo as recently as 1969, not long before he was hired by the IRS. For Casper, finding Richard M. Nixon's name on the Castle Bank customers' list was the one blemish on an otherwise triumphant operation. It was the last thing he had expected, or wished, to find. As he told the author, “I didn't want to believe it.”

After Casper had testified in Washington, Rebozo's secretary called to say her boss wanted to see him urgently. He consulted with IRS colleagues, then agreed to meet Rebozo at his office. The president's friend wanted to know if Casper had actually seen a Nixon

account

at the Castle Bank. Casper replied that he had seen only the customers' list. Rebozo then told him that a Nixon attorney had been to the Bahamas and found “incontrovertible proof” that there was no such account. He produced the lawyer, who had been waiting in a nearby room, and got Casper to tell his story again.

Nixon was “very angry,” Rebozo told Casper, and then asked him about the state of his own finances. When Casper replied that they were not flourishing, Rebozo expressed “dismay” and said he “hoped the situation would improve.” A week later he called about nothing in particular and said again that he hoped Casper's financial situation “would improve in the near future.”

Casper promptly reported these conversations orally and in writing to his IRS contact, a record of which has survived.

_____

If Nixon did have offshore holdings, what were they worth? The original Castle customers' list of course showed only a name and an account number. Although the briefcase later “borrowed” from a bank official contained the list on which Nixon's name did

not

appear, it also held records of Castle's bank and brokerage accounts, copies of ledgers, and extensive correspondence showing how investments were being managed.

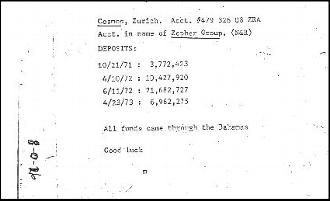

Casper, who was present as IRS photographers took pictures of the papers, was provided with copies of some of them for his work. They included this document, which Casper has provided to the author. It has never been published before:

Â

Taken at face valueâand there is no reason to doubt what Casper says about its originsâthe document appears to be a typed note summarizing four deposits in the Cosmos Bank in Switzerland. It does not indicate whether the sums listed represent U.S. dollars or Swiss francs. If in dollars, then the total of the Swiss bank holding was the immense amount of $42,845,345. If, as is likely, the reference was to Swiss francs, then the dollar equivalent was $11,157,642.

27

The annotation, stating that the funds deposited had flowed through the Bahamas, appears to be a note between bank officials. The “Good luck” is unexplained, and the identity of the writer, “m,” uncertain.

28

Interest in the document of course turns on only one question: Do the initials in parentheses, N & R, refer to Nixon and Rebozo?

The use of initials is consistent with two of Rebozo's other business arrangements. A real estate partnership with banker Sloan McCrae was titled R & M Properties. A company Rebozo formed with Nixon's friend Bob Abplanalp became B & C Investments,

B

apparently for Bob and

C

for Charles (Rebozo's rarely used given name).

According to Casper, the N & R document was one of the many items from the Castle briefcase shared with Herschel Clesner, the chief counsel of the House Commerce and Monetary Affairs Subcommittee. Clesner, who had developed contacts in the Swiss banking community, believed it did signify a record of massive Nixon and Rebozo holdings in a foreign bank.

Casper at first seemed to regret having shown the author the Cosmos document and became highly defensive of Nixon. “I'm not going to clarify a goddamn thing,” he said, sitting in the living room of his modest Florida home. “Nobody got killed. Let it go. The man has enough problems. Some things are better forgotten.” Now in his seventies, Casper made it clear that he was going to take the story with him “to the crematorium.”

Later, however, Casper admitted that a Castle Bank source had “indicated” to him that the “N & R” did refer to Nixon and his best friend. When Casper raised the matter with another staff member, he said, “she clammed up like you wouldn't believe.”

The Swiss bank document, or most of the information in it, matches that provided by another source. In the 1980s, during a meeting with a reporter in his Manhattan home, the A&P heir Huntington Hartford produced a piece of paper with the same Cosmos Bank account number and three of the four deposit amounts that appear on the document seized by the IRS from the briefcase.

In 1996, elderly and ill, Hartford would not discuss the matter. “Do you want to blacken Nixon's name?” he asked. “Don't do it. I didn't think he was so bad. Why would I care if Nixon had an account in a Swiss bank?”

Hartford almost certainly came by his information on the deposits from investigators working on the lawsuit he brought against his Paradise Island partners.

*

Available information strongly suggests a Paradise Island connection with both Castle Bank and Cosmos.

Some of the stock of James Crosby's company, which bought the island from Hartford, was held at Castle Bank. Cosmos Bank subsidiaries, meanwhile, owned 20 percent of the shares in the Paradise Island bridge, the bridge said to have been partly owned by Nixon.

29

In the year of the briefcase seizure Cosmos Bank was a well-established Swiss

Privatbank

operating from an inconspicuous fourth-floor office just off the Bahnhofstrasse, in Zurich. While it revealed little about its dealings, its main activities were described as “business with the United States.” One of Cosmos's early directors had been Robert Anderson, a secretary of the treasury

under Eisenhower, later convicted on charges connected with yet another offshore bank.

30

Cosmos had subsidiary offices in New York, on Park Avenue, and in the Bahamas.

The author's investigation into this matter led him to visit the legendary district attorney of New York County, Robert Morgenthau. As U.S. attorney in the sixties Morgenthau had been the scourge of organized crime, a particular foe of Meyer Lansky's and the first senior U.S. law enforcement figure to probe the arcane secrets of Swiss bank accounts. It was a course that eventually cost him his job.