The Attacking Ocean (26 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Independence from Pakistan came in 1971, after years of ethnic discrimination and political exclusion from a government located nearly 1,600 kilometers away with a far-from-friendly India in between. Cyclone Bhola had come ashore in November 1970, at a time of mounting anger and unrest, on the eve of a national election. Thousands of angry voters, furious at disgracefully lethargic relief efforts, swept the opposition Awami League to victory in the east. Widespread civil disobedience and agitation for independence soon led to the Bangladesh Liberation War, which ended with the formation of an independent Bangladesh in 1971.

1

Bangladesh is a relatively new country, one with a volatile history and endemic poverty, at great risk from extreme climatic events and rising sea levels. The long history of cyclones and storm surges has resulted in enormous casualties and heart-rending tragedies, but at the same time it has produced a citizenry of tough resilience, whose only long-term weapons against the attacking ocean are low-tech solutions, ingenuity, and human power. Long-term efforts involving both industrialized nations and a wide variety of nongovernmental organizations are under way, projects both to combat environmental problems and to cope with rising population densities. For example, an aggressive family planning program and expansion of nonprofit basic health care have reduced the birth rate and infant mortality dramatically.

Despite continued political turmoil and several military coups, the newly independent government turned its attention to disaster relief, drawing on the lessons of Bhola. The authorities and the Red Crescent (part of the League of Red Cross Societies) cooperated to develop a

Cyclone Preparedness Programme, which came into being in 1972 and is designed to raise public awareness of cyclone risks and to train emergency personnel in coastal regions. The administrators of the program faced a daunting task in a country with a long coastline and a delta landscape that lies but a few meters above today’s sea level. Bangladesh is more vulnerable to rising sea levels than any larger nation on earth, with such factors as subsidence and groundwater pollution to combat, as well as a long-term time bomb—massive population growth. The capital, Dhaka, provides sobering numbers. In 1970, 1.4 million inhabitants lived in the city. By 2008, the figure had risen to 14 million. Sober projections speak of a megapolis of 21 million people in 2025. The country as a whole had 44 million inhabitants in 1951. Today a minimum of 168 million people live in one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with 60 percent of them twenty-five years old or younger.

Fortunately, the new government, or perhaps one should say governments in a coup-prone political environment, took the lessons of Cyclone Bhola to heart. One lesson involves the need for efficient early warning systems. As the storm approached, the Indian government had received numerous warnings from ships in the Bay of Bengal. This critical information never reached Dhaka, owing to hostility toward Pakistan. In the end last-minute radio warnings did make about 90 percent of the population aware of the approaching cyclone, but only I percent sought refuge in brick structures capable of withstanding the onslaught of wind and water. Enormous casualties inevitably resulted.

Circumstances had changed greatly when another cyclone arrived in 1991.

2

This time, with much more effective warnings, a small army of trained volunteers fanned out over the countryside ahead of the storm to alert even the remotest communities. They evacuated 350,000 people to 508 cyclone shelters before the storm surge submerged over 160 kilometers of the coastline. The actual situation was more complex, as many people either stayed in their homes or moved to embankments or elevated roadways. Much depended on the distance to official cyclone shelters, or the presence of markets, mosques, and schools, which offered refuge in brick-built buildings. Nearly a quarter of all those who did not reach a brick-built structure perished. About 138,000 people died; 10 million were rendered homeless. But the casualties were far fewer than the half million killed by Bhola.

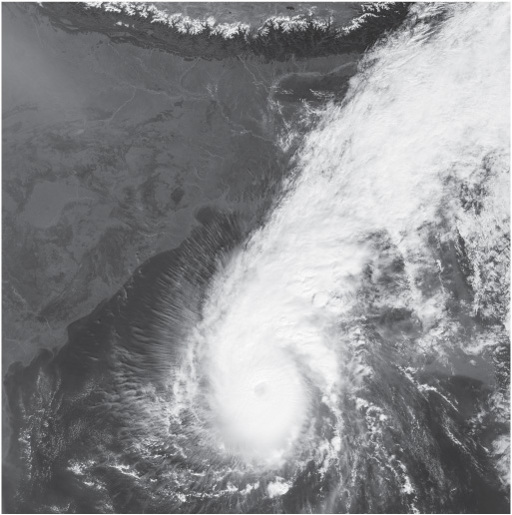

Figure 11.1

MODIS image of Cyclone Sidr close to the mouth of the Ganges River from NASA’s Terra satellite, November 14, 2007. The Category 4 storm is traveling northward over the Bay of Bengal toward the mouth of the Ganges at a speed of 13 kilometers an hour with winds at about 220 kilometers an hour near the storm center. Courtesy: NASA.

Relief efforts are now even more effective. When Cyclone Sidr arrived in November 2007, 42,000 volunteers lived in coastal regions, most of them schoolteachers, social workers, imams, and also local government and community leaders.

3

Thanks to more efficient forecasting, improved radio warnings, and the volunteers, Sidr killed only between 10,000 and

12,000 people, far fewer than its predecessors, despite wind speeds in excess of 260 kilometers an hour and a sea surge that reached six meters. This time, more developed roads and better infrastructure allowed the government to evacuate over 3 million people along the coastline. The authorities distributed blankets, tents, and thousands of tons of rice within hours of the disaster, as 700 medical teams moved into position. As one might expect, casualties were highest on the exposed offshore islands, especially among women and small children.

BOTH FLOODS AND sea levels are part of the volatile environmental equation in Bangladesh. Cyclones and storm surges funnel their way up the Bay of Bengal and across the shallow continent shelf that lies immediately offshore. About sixteen tropical cyclones develop in the bay each year, but not all of them affect Bangladesh. When they do arrive, most in May or November immediately before or after the monsoon season, they tend to affect the southeastern portions of the coast. Such events have been part of the delta climate for centuries. In a warmer future, experts predict that there will be significantly more severe storms and sea surges and about 10 percent more monsoon rainfall as well as higher temperatures. With higher sea levels, the effects of the surges will be felt even farther inland than they are today, with an accompanying rise in soil salinity. At the same time, the farmers and fisherfolk of the coast will have to adapt to river floods on a greater scale than in the past.

4

Most of Bangladesh’s rainfall occurs during the monsoon months between June and September, when the country’s three great rivers unleash both floodwaters and about a billion tons of sediment on the delta—from a catchment area twelve times the size of the entire country. Such inundations are a fact of life in Bangladesh. The delta farmers are accustomed to seasonal flooding and survive comfortably most years. As much as a quarter of the country vanishes underwater during a normal monsoon season.

5

This figure can rise as high as 70 percent in exceptional years. Very severe floods are another matter and can cause major loss of life, especially today, when population increase is rapid,

cities are growing, and a combination of other forms of economic development and poor maintenance of flood works come into play. Some authorities have even argued, quite reasonably, that it may be impossible for Bangladesh to develop a twenty-first-century economy without proper management of the disaster risks posed by floods—this before one factors in sea surges and rising sea levels.

Major floods have wreaked significant destruction to crops and the national economy in at least five years of the past thirty. The flood-waters rise over low riverbanks, break embankments, and flow out over the featureless landscape. In normal years, many villages are like islands on low mounds across the plain. Each household constructs an elevated platform inside its house to raise its family above the climbing water. This works surprisingly well, except when exceptional floods bring havoc, sweeping everything before them. Hundreds of people routinely die, the damage to infrastructure, crops, and small business often numbering in the billions of dollars. In earlier times, when population densities were lower and urban expansion and industrial activity more muted, much of the flood passed into wetlands surrounding Dhaka and other cities in a form of natural flood relief. The government has issued regulations that outlaw infilling for buildings, but developers blithely ignore them, especially around the capital. Both the poor and the workers, who then live and labor on these lands, are now at much greater risk, many of them immigrants from outlying areas who are unaccustomed to flooding, especially that caused by the sudden breach in an embankment.

Floods and rising sea levels profoundly affect agriculture. Three quarters of Bangladesh’s cultivable land is under rice, most of it traditionally grown using the monsoon rains, and also the residual moisture in the ground after the water recedes during the dry season. A big flood erodes riverbanks and embankments, sweeps away entire villages and their land. Muddy water can inundate the landscape for weeks, even months, and devastate traditional

aman

rice varieties that do not like prolonged immersion. During the 1980s, many farmers turned to irrigation agriculture, using a form of dry rice, known as

boro

, which requires a higher capital investment in dikes and earthworks, but is not dependent on ca

pricious rains and floods. Higher sea levels near the coast increase soil salinity, but new strains of both crops can be grown under more brackish conditions. While diversifying crops, the government is building up contingency food reserves and food storage facilities to tide people over lean years.

Cyclones, floods, and sea surges remodel the landscape from one year to the next. Even with satellites, computer models, and vastly improved communications, communities living in at-risk areas near the coast, on offshore islands often called

chars

, or near river embankments have to adapt to constantly changing environments. An embankment break or an eroding river can destroy a village and its fields in hours. The inhabitants can do nothing but move to higher ground until the water recedes. They then try to find vacant land nearby to rebuild, usually a difficult task in an increasingly crowded landscape. Sometimes they move onto a wealthier kinsman’s property in exchange for some nominal labor. Their old homes are gone forever, but the rivers are so volatile that they can often rebuild on newly formed land that appears without warning as the water falls. But the chances are that they will have to move again. Many landowners become landless, take on mortgages they can ill afford, and live in an endless debt cycle.

However, the basic mechanisms of survival are at least partially codified in law and go back centuries. One can call these people environmental migrants, but almost invariably they move elsewhere temporarily, then return when circumstances permit. They have no desire to leave their ancestral lands, with all the emotional and spiritual ties that underlie the community. Villages on the mainland shift locations again and again in response to flood and sea surge, but they never move far if they can avoid it, even if several members of each household, especially the young men, travel to cities to find work so they can send money home. During severe floods, some families move onto boats. When erosion on an offshore island like Hatia, at the mouth of the great river estuary on the southeast coast, results in the loss of land, the immediate response of those affected is to move to their in-laws’ homes, away from the immediate threat. Then they wait for natural accretion of flood deposits to create new land that they can claim.

What will happen in the future, if warmer conditions bring stronger and more frequent cyclones, and Himalayan glaciers far to the north melt faster and swell the great rivers hundreds of kilometers downstream? Most of Bangladesh lies on the fertile alluvial plains of the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers. Even with reduced flow, their courses shift constantly, making it hard for the rivers to build up high banks. Would conventional flood works provide a solution? Expensive international schemes proposed by the World Bank envisage building nearly eight thousand kilometers of dikes to control the rivers, at a cost of ten billion dollars, but many local farmers oppose the scheme, as it would result in forced changes to their farming methods. Nor would massive dikes like those in the Netherlands solve the problem, for the subsoil is alluvial sand and mud, which shifts constantly. In any case, Bangladesh lacks the funds to pay for such expensive solutions.

The best solutions appear to lie with the people themselves and with judicious government investments in infrastructure and flood-protected housing. Numerous farmers are building houses on stilts that stand above even the most severe floods. There are smaller-scale solutions as well, among them simple dwellings with cheap jute panel walls that are easily replaced after a flood that are built on half-meter concrete plinths. At the same time, Care and other organizations are encouraging farmers to use long-abandoned farming methods that include floating gardens, well suited to areas that are flooded for long periods of time. Bamboo and dense beds of hyacinth, as well as last year’s decomposed vegetation, create floating gardens that allow the growth of vegetables for sale in markets for most of the year, with much higher yields. Salt-resistant rice varieties are another solution, as are fast-growing crops that can be harvested before the monsoon rains arrive. A policy of breaching earthen dikes to encourage silt deposition as the water drains away helps the land rise and counterattacks the effects of rising sea levels.