The Attacking Ocean (28 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Arctic barrier islands are more vulnerable to climate change than any other such formations in the world. For thousands of years, permafrost and sea ice have protected them from wave damage during storms. Now sea levels are climbing aggressively by geological standards. Islands in the far north are said to be eroding three or four times faster than those farther south in the United States. If the erosion accelerates, many Arctic islands will vanish and the Eskimo communities living on them will face an uncertain future.

Today, most villages along the Chukchi Sea coast are clusters of heavily insulated government-issue homes that protect their occupants against a climate where ice is at their doorsteps for nine months a year—or was until recently. Today, ice-free conditions along the shore last for as long as four months, sometimes more, along Alaska’s North Slope, even longer farther south. Now fall and winter storms bring waves that break against the fragile barrier islands, smashing the melting permafrost that once helped make the beaches natural seawalls. A combination of rising sea levels and greatly accelerating erosion are playing havoc with the communities that have used Arctic barrier islands for a very long time. The US government estimates that at least twelve Native American

villages are facing possible destruction. Another twenty-two coastal communities will require some form of immediate protection from climbing sea levels and its consequences. The people of these villages, who are still subsistence hunters, once moved easily in the face of changing climatic conditions and the seasons. Living permanently in places that still make sense in terms of hunting strategy, but are not necessarily the best places, has made these isolated communities highly vulnerable to rising sea levels in ways that were unimaginable in ancient times.

Figure 12.1

Maps showing Alaskan locations in

chapter 12

.

Shishmaref, on the shores of the Chukchi Sea, lies on a six-kilometer-long island, a settlement occupied by 580 subsistence hunters. People have visited here for at least four thousand years, probably much longer. Until recently, the Eskimo used the island as a winter camp, fanning out to other island encampments in the summer.

4

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Shishmaref became a harbor for shipping gold-mining supplies inland and permanent occupation began. Now the community is under serious threat from rising sea levels, with only limited options for long-term survival.

Figure 12.2

A house falls into the sea at Shishmaref, Alaska, September 27, 2006. AFP Photo/Gabriel Bouys Files/Newscom.

One option has been in play for a while—constructing sea defenses. Since the 1950s, the community has tried a variety of measures, including oil drums and sandbags, even household refuse, to protect the settlement against storms. In 1984, Shishmaref built a 520-meter seawall of wire baskets filled with stones. Storms promptly removed sand behind it, but the wall did slow coastal retreat. Next came a barrier of cement blocks, linked by cables to form a mat and placed against the face of the coastal dune, designed to bend when sea ice pushed against it. The mat failed in short order. Even if successful, the walled area actually enhances the problem, for the sea is cutting back on both sides of it and turning the village into a headland and a juicy target for storm waves. By late 2006, some thirty-four million dollars had gone into seawalls to protect the community, a staggering expense to protect less than six hundred people and more costly than all the structures in the village.

Then there’s a second option: Remain on the island and shift threatened homes to new locations. Eighteen houses were moved back from the shoreline after a 1997 storm. However, wherever one places houses on the island, they are still threatened by ongoing erosion, so the only path for long-term survival would be a community protected by prohibitively expensive high seawalls. Such an adaptation scenario would also require the construction of storm shelters and the preparation of evacuation plans that could be implemented in very harsh weather and at short notice.

A third option: Move to neighboring villages or to larger communities such as Anchorage, Kotzebue, or Nome. Joining nearby subsistence-based villages would place local food resources under threat, apart from the complexities of traditional rivalries, some of which go back generations. Migrating to cities or towns would mean the immediate loss of a subsistence lifeway that dates back many centuries and is the last surviving element of a once-thriving culture. Both Kotzebue and Nome, with populations in the range of three thousand to four thousand, are prepared to accept the villagers, but how would the hunters and fisher-folk support themselves in their market-driven economies? To add to the

complications, they would come from a totally dry community to towns that have serious problems with endemic alcoholism.

There remains a fourth option: Move Shishmaref and other threatened barrier island communities to higher ground. The idea was first mooted as early as 1973, but it was not until 2002 that the villagers voted to move to a new site over a period of years. Shishmaref’s new site on the mainland is known as West Nantuq, across a lagoon. An Army Corps of Engineers study in 2004 estimated the cost of relocation at $180 million, including moving 137 homes across the frozen lagoon in winter and bringing in some additional prefabricated houses by barge. The federal government is expected to pay for everything, including the complete infrastructure for the village and a new harbor. Shishmaref may have ten to fifteen years before it vanishes. Meanwhile, relocation plans move along glacially slowly.

Other coastal Alaskan villages also wrestle with rising sea levels, among them Newtok on the Ninglick River considerably farther south, a place close to the Bering Sea that fisherfolk and hunters have visited for at least two thousand years. Some three hundred Yupik Eskimos live in the village, which is rapidly being washed away by erosion caused by the ever-widening river. The villain is rising temperatures, which have reduced ice cover, brought more frequent storm surges, and thawed the permafrost, which formed a buffer against the Bering and formed a solid foundation for Newtok. Now the underpinning is turning to squishy mud; buildings including the old school and community church have buckled and are sinking. Wooden boardwalks connecting the buildings literally float on the muddy ground. The river gobbles up as much as 27.5 meters of dry land each year. Newtok is below sea level and sinking, an island caught between the Ninglick and a nearby slough. The village will have vanished within a decade or so.

Newtok has but one future—to move to a site on Nelson Island, 14.5 kilometers away, which the villagers acquired in 2003 through a land swap with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They named the new settlement Mertarvik, “getting water from the puddle.” The community then obtained funds for building a barge landing for offloading the

materials needed to construct the infrastructure for the new settlement. Infrastructure is being installed slowly; house construction started in 2011. The cost of the move is unknown, but government estimates of two million dollars a household seem absurdly high.

There are no normal provisions in federal or state budgeting for funds for a community facing not the devastation of a fast-moving climatic event like Hurricane Katrina, where emergency funding was available in short order, but rather a slow-moving disaster that will eradicate a village of isolated subsistence farmers after decades of slow death. None of this will be cheap and none of it easy for the local people, who are severing ties with village sites where their ancestors lived for many centuries.

At least Newtok, Shishmaref, and other Alaskan villages can move to nearby higher ground—if someone will pay for the relocation. But what happens when your home is completely surrounded by water and lies only a few meters above sea level, as is the case in the island nations of the Pacific and Indian Oceans?

LIVING ON A Polynesian atoll, you can never tune out the sound of ocean breakers. You are at most some four or five meters above sea level. When severe storms descend, you are almost certain to get wet. To live sustainably on such isolated and tiny spots of land in the past required not only water but also a set of adaptations. As a result, every inhabited low Polynesian atoll is a humanly modified environment, complete with seawalls and pits for growing taro, a staple root crop in the South Pacific, the soils often formed of the refuse from human occupation. A few plants have always provided food and essential raw materials—coconuts, with their fluid, meat, and leaves for weaving, pandanus for both food and leaves. Both do well in the salty environments of tropical beaches. Breadfruit and taro can be grown, both requiring water, and the latter grown in artificial pits mulched with leaves and other organic detritus. Inevitably, survival depended on social contacts and trade with other islands, maintained by long-distance voyaging in outrigger and double-hulled canoes.

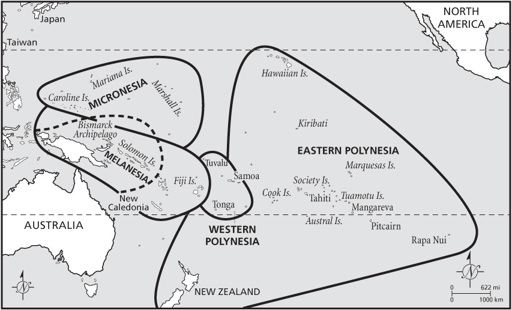

Both Tuvalu and Kiribati, described below, are Polynesian outliers, settled not from the west like other Micronesian islands, but from the south, from the heart of Polynesia. Intensive studies of radiocarbon dates from Polynesian islands place the first voyages eastward from Fiji and Samoa at around the eleventh century C.E. Both Tuvalu and Kiribati may have received their first inhabitants at about that time: We don’t know.

5

Once settled on a small island, however remote, you were never stuck in one place. There was a great deal of movement in Tuvalu and Kiribati’s world, for no island in this part of Polynesia was completely isolated from others over the horizon. That was the strength of Polynesian society and its greatest weapon against an attacking sea—the ability to move elsewhere on short notice. Today, frontiers set over the past century by colonial powers create artificial barriers at a time of fast-rising populations. The ancient, more flexible world is no more. Many Pacific islands face an uncertain future as independent nations in an intensely competitive, global world.

Tuvalu comprises four reef islands and five atolls located in the heart of the Pacific midway between Australia and Hawaii.

6

At twenty-six square kilometers, Tuvalu is the fourth-smallest nation on earth. Only Monaco, the Republic of Nauru, and Vatican City occupy less area. There are 10,500 inhabitants on eight of the nine islands. The highest point lies only 4.6 meters above sea level.

Some canoe loads of people had settled on Tuvalu by at least a thousand years ago, probably from Fiji or Samoa. Sporadic European contact began when the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira sailed through the archipelago in 1568 while on a search for the mythical Terra Australis, the great southern continent, but he was unable to land. Foreign visitors were rare until the nineteenth century, except for the occasional whaler, but landing was always difficult. Nevertheless, slave traders, “blackbirders,” removed nearly four hundred men from the islands to work in the notorious guano mines on the Chincha Islands off the Peruvian coast between 1862 and 1865. By 1865, Christian missionaries and foreign traders were active on the islands, which became part of the British colony of Gilbert and Ellice Islands from 1916 to 1974. Tuvalu

became an independent nation within the British Commonwealth in 1978, but it is a nation at serious environmental risk, lying as it does only a few meters above an inexorably rising Pacific.