The Attacking Ocean (12 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Here, rising sea levels helped foster farming and civilization, but at the same time created environmental problems—among them rising salinity—that have plagued farmers between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers ever since. Here, too, climate change, in the form of shifting rivers and rising sea levels, was a crucible for intercity strife and petty wars. For the first time in history, standing armies became instruments of rulers’ policy. Here and elsewhere, warfare was to become endemic in human life. For the first time, too, shifting patterns of international trade made anchorages and ports at the ocean’s edge major players in the rise and fall of civilizations, and in human relationships with the ocean.

Around six thousand years ago, the world’s oceans had reached more or less modern levels. Dramatic geographical transformations were a phenomenon of the past, except for local crustal adjustments, lengths of coastline elevated or lowered by earth movements, and natural subsidence. The sea still attacked, but in different ways in human terms. Those who dwelled by exposed coasts had always experienced violent storms, storm surges, and tsunamis, but their numbers were small, most communities little more than long-occupied fishing camps, farming villages, or small towns. There were casualties from surges and tsunamis, from natural catastrophes wrought by the ocean; there always had been and always will be. Nevertheless, the numbers of coast dwellers and people living close to sea level were minuscule even by the standards of two thousand years ago when Rome ruled the Mediterranean world and Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi unified China into a single kingdom. The casualties wrought by severe weather events and natural cataclysms rose dramatically with the founding of the first cities some five thousand years ago, as well as with the rising importance of long-distance commerce, much of it carried by ships sailing from ports large and small.

The next six chapters examine some of the changes wrought in human societies by extreme events that originated in the ocean after six thousand years ago. Our chronological starting point is around 5000 B.C.E., usually later. For the first time I venture at times from the past into the present, something we dwell on at greater length from

chapter 11

onward. Where I move from past to present is where I perceive a degree of continuity in the story that is worth pursuing in, say, the wider context of Mediterranean history or in China, where the Yangtze River

shaped the birth of modern-day Shanghai. Here too we begin to define some of the issues that confront nations living close to sea level. Do you yield to the attacking ocean, staying where you are and adapt, or wall yourself off from rising sea levels and violent storm surges? These issues have been at the forefront of Venetians’ minds for many centuries, have affected government policy and sea defenses in the Low Countries since medieval times, and have resonated through the halls of the British Raj in India. The chapters that follow are, as it were, the starter for the main course of today’s inundations, the closing chapters of the story.

As before, we begin our journey in northern Europe.

5

“Men Were Swept Away by Waves”

Doggerland finally vanished in about 5500 B.C.E. as the last remnants of the Dogger Hills disappeared beneath the heaving waters of the rising North Sea. This was not a dramatic event, just a gradual encroachment of saltwater on low-lying terrain. As groundwater and sea levels rose, so inland swamps and freshwater lakes formed along the coasts of what are now the Low Countries. A layer of peat developed over many centuries, but never became very thick. The rising North Sea also turned much of the coastal landscape into muddy tidal flats and extensive tracts of landscape that dried out at low tide. When sea level rise slowed, the surf threw up sandbars that eventually became dunes. Eventually lagoons close to the coast silted up and became freshwater marshes where peat continued to grow, turning much of the Netherlands into a huge bog. Today two thirds of that densely populated modern country is basically an alluvial plain that is vulnerable to flooding.

The rising sea encroached inexorably on the land, but human existence continued much as before. As they had in Doggerland, small hunting bands frequented lakes, marshes, and wetlands where plants, fish, game, and fowl could be found at all seasons of the year. Many places along the low-lying coastlines of both Britain and the Low Countries supported a great diversity of productive environments during the five millennia between the disappearance of Doggerland and the Roman colonization of Europe. Along what is now the Belgian coast, a patchwork of tidal flats, lagoons, and freshwater peatlands lay behind a belt

of sand dunes. Farther north, in the western Netherlands, four major river estuaries, each with extensive salt marshes and mudflats, broke up a virtually continuous sand dune barrier. Freshwater peat bogs developed in the sheltered conditions behind the natural blockade. A more open coastal plain, protected in part by low offshore islands, marked the northern Netherland and German coasts. Here again, mudflats and salt marshes dominated the landscape, interspersed with freshwater swamps. Eastern England’s rivers and swampy estuaries also supported hunting groups for thousands of years. In these lowland landscapes, fish runs, migrating waterfowl, deer hunting, and the seasons of plant foods, not the ocean, set the pattern of human existence for nearly a thousand years.

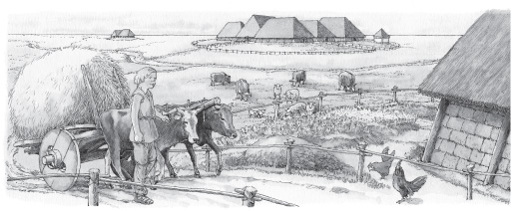

THE NETHERLANDS COAST, midwinter, 3800 B.C.E. A bitter wind howls across the salt marsh, carrying the sound of a roaring sea on a fast-rising tide. Snow flurries cascade with the storm; the gusts strengthen and turn swirls of snowflakes into whirlwinds. A narrow levee overlooks the turbulent ocean raging across the flat landscape, a slender bastion set against the gale. A huddle of grass-and-reed huts crouches atop the ridge, set in a circle within a wooden enclosure crowded with cattle and sheep. As the hours pass and the tide rises, the encroaching tide attacks the levee. Great waves break against the low ridge; spray breaks high over the low-set dwellings; waterlogged cattle low in distress. A few breakers sweep into the margins of the settlement and flood one of the huts, which collapses in a confusion of reeds and sticks. Drenched to the skin, the family inside quickly make their way to another shelter on the far side. The villagers anxiously watch the advancing surge, knowing that eventually the tide will turn and the sea recede.

IT’S CONJECTURE, OF COURSE, but a reflection of a new reality: Farming introduced a completely new dynamic to life along the North Sea. Hunting bands could ebb and flow with the coastline, their possessions readily portable, their lives attuned to mobility. But farming anchored people to the

land, to their growing crops, to the pastures where their flocks and herds grazed. Now the North Sea became far more than background noise to daily existence. The ocean became a potential enemy that could wipe out fields and flood pastures in hours, leaving people hungry.

At some point, perhaps as early as 4700 B.C.E., a few hunting groups acquired cattle and perhaps sheep from farming communities, presumably on the uplands.

1

What compelled them to do so remains a mystery. Perhaps rising sea levels and growing populations created pressure on hunting territories and led to food shortages. Thus, it would have been a logical step to broaden the food supply by herding domesticated animals. Presumably only very small numbers of animals were involved at first, perhaps acquired from farmers on higher ground, who drove their flocks and herds onto salt marshes during summer. Several centuries passed before cereal crops came into use in the wetlands. Judging from excavations at Swifterbant near the Zuiderzee, the people cleared vegetation on clay levees, then grew summer crops of emmer wheat and barley in small fields. They also harvested large numbers of wild plants, including hazelnuts, which may have been an important staple, provided one could store them. A cubic meter of hazelnuts is sufficient to provide 10 percent of the annual energy needs of a mixed population of twenty people.

2

At first the changeover made little difference to seasonal routines. Families moved their cattle and sheep to salt marshes and flatland grazing in spring. Come winter, each community must have driven its flocks and herds as far above high tide as possible. As both cereal farming and herding took hold, so the human grip on wetlands became less transitory. When sea levels receded slightly, small groups of people would settle permanently on the better-drained fringes of peat bogs and on raised creek levees. Such locations enabled them not only to eke a living from their animals and fields, but also to exploit wild plants and nut harvests, waterfowl and fish of all kinds if they wished. By the first millennium B.C.E., permanent settlement was commonplace, even if human populations were still thin on the ground. There was good reason. Even modest but lasting farming settlement near the coast brought a quantum jump in vulnerability to major storms, extremely high spring tides, and fast-moving sea surges that raged far inland carrying everything before them. Life became a permanent tussle against the North Sea, a war that continues to this day.

Figure 5.1

Map of locations mentioned in chapters

5

and

14

. The islands around Strand, Germany, are not included.

Backbreaking labor and constant vigilance were the only human weapons against the ocean. Building even modest dikes consumed days of brutally hard work in landscapes where the only natural defenses were sand dunes and elevated levees. The problem was particularly acute along the northern coasts of the Low Countries, where tidal flooding

and sea surges were endemic. Such events might lay waste everything before them, but they did lead to the formation of elevated coastal marshes with freshwater bogs behind them. As the drainage improved, so farming villages appeared along the Dutch coast by the sixth century B.C.E. and along the northwestern German shore a few centuries later. Each settlement lay on elevated marshland. As water levels rose slightly after 1000 B.C.E., some farmers left home, but others fought back with artificial raised mounds made of turves and clay known as

terpen

(singular,

terp

), which translates as “staying above water,” located in places where they could escape high tides most of the time.

3

The number of such mounds rose and fell as water levels fluctuated, to the point that by the fourth century C.E., a time of rising shorelines, only the most elevated coastal marshes were still occupied.

Many terpen had long histories. At Ezinge near Groningen, the first settlement of the fifth century B.C.E. lay on the surface of a salt marsh, set within a palisade about thirty meters across.

4

Three rectangular buildings with wattle-and-daub walls and thatched roofs lay inside, along with a barn set on wooden piles to keep stored crops dry. The next settlement some three centuries later stood on a mound of turf sods about 1.2 meters high and 35 meters wide. Four farms huddled together on the terp for protection against winter storms. Later farmers repeatedly added to the mound, which eventually reached a height of 2.2 meters and a width of 100 meters. During Roman times, the tumulus grew even larger, but was still a huddled group of four farmsteads that perished in a fire during the third century C.E.

Most terpen lay close to the seaward side of the salt marshes, often on low ridges running parallel to the shore. No less a literary personage than the Roman eminence Pliny the Elder wrote in his

Natural History

of such settlements, located in the “regions of the far north … invaded twice each day and night by the overflowing waves of the ocean … Here a wretched race is to be found, inhabiting either the more elevated spots of land or else eminences artificially constructed and of a height to which they know by experience that the highest tides will never reach.” The mound dwellers had no flocks and wove nets from sedges and rushes “employed in the capture of the fish.”

5