The Attacking Ocean (13 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Figure 5.2

Artist’s reconstruction of a terp at Ezinge, the Netherlands, ca. two thousand years ago. © Bob Brobbel.

Archaeology tells us that Pliny was wrong in calling the terpen dwellers mere fisherfolk. The mound people were expert farmers, growing barley and other crops such as flax that can tolerate quite salty soils. They maintained herds of cattle and also sheep, which thrived in brackish marshlands. Wetland agriculture was a world unto its own, practiced by people who probably kept to themselves with little contact with outsiders.

The Romans found little attractive in the Netherlands’ flood-beset swamps and dank woodlands. There were no minerals; the agricultural potential appeared low, and the population sparse. Only its geographical position was important, for the mouths of the Maas and the Rhine Rivers led deep into western Europe and hostile Germanic tribes could travel along them into the rich landscapes of Gaul. Julius Caesar was the first to attempt a stabilization of the northern frontier in 57 B.C.E., but the Roman hold on the Netherlands was never much more than nominal. Frequent campaigns against Germanic tribes sometimes ended in disaster, among them a campaign in 12 C.E. A Roman general, Publius Vitellius, set off for winter quarters through marshy terrain during a severe North Sea gale. The historian Tacitus tells us how:

after a while, through the force of the north wind and the equinoctial season, when the sea swells to its highest, his army was driven and tossed hither and thither. The country too was flooded; sea, shore

fields presented one aspect, nor could the treacherous quicksands be distinguished from solid ground or shallows from deep water. Men were swept away by the waves or sucked under by eddies; beasts of burden, baggage, lifeless bodies floated about and blocked their way.

6

MANY PEOPLE ASSUME that the North Sea and the Baltic stabilized after the flooding of Doggerland and remained largely unchanged since about 5000 B.C.E. This assumption has led to hysterical predictions of disasters caused by the seemingly unique (but real) sea level rises of today attributed to humanly caused global warming. In fact, northern coastlines have changed irregularly and unpredictably over the past seven thousand years. We will probably never be able to chronicle all the minor sea level changes that have affected the North Sea, except in the most general terms. Local topography, the configuration of the shore, tidal streams, and adjustments in the earth’s crust all play significant, and still little understood, roles in the process. So the brief summary of what happened after 1000 B.C.E. that follows is cursory at best.

7

During the late first millennium B.C.E., salt marshes and mudflats formed most of the coastal wetlands in northwest Europe, with extensive freshwater swamps behind them in many areas. By the first century B.C.E., there was a period of relatively stable, even falling, sea levels throughout eastern Britain and in much of the Low Countries. However, during late and post-Roman times, there are widespread signs of sea level rises between the third and fifth centuries C.E., which resulted in the inundation of numerous marshland settlements and once-settled agricultural land. Whether the abandonment of these villages was due entirely to sea level rise is questionable, as this was also a period of major economic and social upheaval. Over many centuries, people living close to sea level either reconciled themselves to settling on higher ground or counterattacked the sea with the first humanly fashioned defenses.

At first, farmers on both sides of the North Sea had settled on locally slightly higher terrain close to natural canals, creeks, and ditches. By judicious, communal effort, the villagers could drain water from small tracts of land, which were mainly used for grazing cattle. They could

also construct low embankments to protect areas from summer floods. The terpen of the northern Netherlands and Germany were a logical extension of these landscape modifications, whereby farming villages lay permanently within tidal landscapes. From there, it was a simple step from marshland modification to the partial transformation of landscape by constructing earthen seawalls. Once a low earthwork was in place, the farmers could then gradually enclose land on a piecemeal basis as the local population rose. Alternatively, and more rarely, they could reclaim large areas of land as a planned, systematic enterprise.

At first there were no seawalls along the Netherlands coast. Nevertheless, farmers attempted to control flooding with dams and sluices. At Vlaardingen in the western Netherlands, a first-century landscape of paddocks and farming settlements lay along tidal creeks.

8

Dams constructed of clay sod with layers of reeds and sedges and revetted with sharpened stakes blocked creeks and side drainage channels. Hollowed tree trunks allowed freshwater to flow under the dam, each with a hinged wooden flap valve at the end of the culvert.

Land reclamation, even on a small scale, required long experience and an intimate knowledge of tidal streams, wave patterns, and natural drainage. Even a modest earthen seawall a few meters high was an ambitious enterprise, at best a high-risk endeavor. Months of backbreaking digging through layers of gravel and piling up thick clay and turves in small basketloads in all weathers could be swept away in hours. Just planning the job could take days of argument and discussion. Who would undertake foundation digging, the collection of turves, even the weaving of strong baskets for moving soil? Above all, what were the long-term benefits for the community, and perhaps its neighbors? We can imagine long arguments and counterarguments among people who had no illusions about what lay ahead, not only in constructing, but also in maintaining the low dikes once they were in place. Everyone knew that the long-term rewards could be significant, even for generations as yet unborn, but the risks were significant. Seawalls were vulnerable to high tides, to sea surges, and they placed a heavy burden of watchful maintenance on those who lived behind them.

Centuries of hard-won experience came into play during seawall construction. Each formed a continuous barrier that prevented inundation year-round and reduced waterlogged acreage. The absence of water improved soil aeration and helped warm the earth more rapidly in spring. As a first step, major flooding sources had to be controlled, not only tidal flow, but also water runoff from higher ground. Once this level of control was in place, constructing drainage systems could lower water tables. All of this was a laborious, slow-moving task carried out for the most part by individual communities. Fortunately for the diggers, early seawalls along the North Sea were relatively modest because of lower sea levels at the time. Exact dimensions are hard to come by owing to later sea surges and tidal action, but even as late as the eleventh and twelfth centuries C.E., an embankment near Enkhuizen in the northern Netherlands was only 1.6 meters high compared with the 6 meters of today.

9

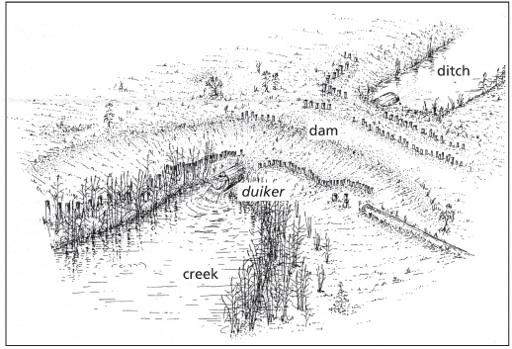

Figure 5.3

Artist’s reconstruction of a Roman period dam and drain that crossed a tidal creek at Vlaardingen, Netherlands, ca. 75–125

C.E.

The drain, or

duiker,

consisted of two hollowed tree trunks, one fitting into another. The hinged flap was at the outer end. © B. Koster/Vlaardings Archeologisch Kantoor.

To build an earthwork like a dike or seawall required digging the raw material from nearby marshes and the foreshore. Each community felled hundreds of trees inland for bridges and sluices, then dragged the trunks along narrow tracks through marshy terrain. Much remained to be done when the seawall was complete. While the builders could make some use of natural drainage channels behind the embankments, they also had to create an entirely artificial system. Even when the seawall was finished, the work never ceased. The defenses had to be inspected regularly, especially after winter storms. Local villagers had to clean and scour the drainage ditches regularly by hand. Fortunately, the sludge could be spread on nearby fields to improve soil fertility. The risk of sea surges and catastrophic flooding was always present.

Early reclamation efforts usually involved simple earthen embankments built of marsh clays, usually strengthened with timber stakes, wattle fences, stones, and straw. The work had to be completed rapidly; winter storms soon washed away unfinished fortifications. Once the seawall was complete, water flowing from higher ground had to be channeled across the reclaimed land, either by digging a channel or, in some cases, by using a raised watercourse. Seawater drained through elaborate systems of gullies and ditches, often using a combination of plowed furrows and larger drainage ditches excavated by hand that also served as field boundaries. The same defiles provided water for livestock. Within a few years, all the salt was washed from the reclaimed soil, which could then be used for pasture or enriched with lime, marl, or manure to turn it into arable land. All this effort could come to naught in the face of a spring tide, a winter gale, or a sea surge that swept away dikes, dwellings, flocks, and people.

The threat from the sea was always there. As Christianity took hold, so natural disasters became a symbol of the wrath of God. No one could predict great gales and storm surges. High waves and coursing tides could return year after year or remain just a silent menace in the background for generations. Most such disasters have long vanished into historical oblivion, but a few memorable cataclysms survive in medieval records. In 1014,

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

describes how in eastern England “in that year, on the eve of St. Michael’s mass, came the greatest

sea flood wide throughout this land, and ran so far up as it had never before had done, and washed away many towns, and countless numbers of people.”

10

BETWEEN 500 AND 800 C.E., falling sea levels led to the formation of the so-called Young Dunes, which now form a practically unbroken coastal rampart from Den Helder in the north to the Hook of Holland in the south. Then an unexpected sea level rise penetrated deep into dune country between 800 and 950 C.E., at which point serious dike building finally began. Because of the higher sea levels, terpen in the northern Netherlands and northwestern Germany were at their most numerous during the tenth century, many of them built on marsh bars and alluvial ridges. Some now reached a large size, surrounded by a circular road and ditch. A freshwater pond usually lay in the middle of the village; wells lined with wooden barrels sunk deep into underlying peat and sand provided additional water supplies. The villages looked like islands, surrounded by orchards and trees, dominated by a church tower, in the midst of treeless salt pastures.

11

Around 1000 C.E., the North Sea again receded slightly, giving some respite from storm surges and warfare. Populations rose. Many communities now began the task of protecting their lands from both storms and the insidious penetration of saltwater inland. The first dikes were little more than raised trackways that led from one terp to another, soon extended to form closed systems of water defenses. Simple barriers crossed creeks or ditches, at first fully removable and then replaced by simple wooden sluices that opened and shut with ebb and flood.

Despite these sea defenses, repeated flooding attacked the region during the sea level rise of the slightly warmer late Medieval Warm Period after 1000 C.E. In the north, tens of thousands of people lost their lives during a storm surge between Stavoren, now on the Zuiderzee, and the mouth of the Ems River in 1287. Subsequent inundations flooded huge tracts of coastal land. The only defense at the time was to raise terpen heights. Ezinge was now 18 meters above the surrounding landscape and nearly 425 meters across.

To the south, the waning sea level rise between 950 and 1130 coincided with a rise in population at a time when the threat of constant Norse raids receded. Farmers needed more cultivated land; drier, less severe winters and a decrease in storminess led to aggressive settlement along bogs by burning off vegetation, then digging ditches for drainage and property boundaries. Extensive colonization transformed hitherto uninhabited peat swamps into farmland. Soon major landowners became increasingly involved in larger-scale land reclamation.

AROUND 1130, AN increase in storminess and the resumption of sea level rise caused havoc. As the unpredictable sea surges continued, individual communities cowered behind their own, usually inadequate, defenses. Perhaps they felt powerless in the face of divine wrath, which gave them little incentive to organize their water defenses. Few villagers looked farther afield than their own fields and grazing grounds, or thought of anything but their own parochial interests. Prominent landowners and religious houses led the way and did most of the larger-scale diking. Thanks to their efforts, sea defenses slowly extended along lengthy stretches of the coast and blocked river breaches, many of them haphazardly.