The Attacking Ocean (10 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Figure 4.1

The Persian Gulf during the Late Ice Age, ca. twenty thousand years ago.

Rising seawater reached the present-day northern Gulf region between 7000 and 6000 B.C.E.—at about the same time as the English Channel separated Britain from the Continent and Doggerland finally disappeared under the North Sea. Shallow Gulf waters quickly inundated a low-lying delta region, turning it into a shallow marine lagoon environment, both raising the water table and shallowing the river gradients. The floodwaters of the Euphrates and Tigris still surged to the ocean, but the deep channels of earlier times now lay under ever-deeper layers of silt carried from upstream. Each summer the inundations over-flowed natural levees or shallow riverbanks and flooded the flat landscape. An extensive marine estuary formed inshore of the expanding coastline. By 4000 B.C.E., the Gulf shoreline was as much as 2.5 meters higher than today in some places, so much so that geologists have identified ancient

marine sediments some four hundred kilometers north of the modern northern Gulf coastline. One estimate places the northern Gulf coastline as far as two hundred kilometers north of its present shore as recently as 3200 B.C.E.

The sea level rise coincided with an increase in seasonal rainfall across the Arabian Peninsula and southern Mesopotamia between about 9000 and 8000 B.C.E., associated with powerful Indian Ocean monsoon activity that lasted until about 4000 B.C.E. River runoff increased; lakes formed between dunes on the Arabian Peninsula; pollen grains from Israel and Oman testify to less arid vegetation across the landscape. Less direct geological clues add to the portrait of a slightly better watered region, among them a lattice of seasonally active wadis (gullies) that drained into the growing Gulf and the Arabian Sea. Both deep-sea cores and terrestrial indicators tell us that humidity remained relatively high until about 4000 B.C.E., when aridity increased gradually over many centuries.

The changes in rainfall patterns resulted from changing monsoon patterns brought about by a northward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone in the Indian Ocean.

3

Minor changes in the tilt of the earth’s axis brought warmer summers and colder winters. Around 3500 B.C.E., the monsoons weakened further and climatic conditions became much more arid. Lakes dried up; dunes formed over wide areas at the southern edge of the Gulf. Cores from the Arabian Sea reveal major dust storms. Greater aridity coincided with the deceleration of sea level rise and altered the Mesopotamian environment significantly. The rivers ponded, flowing outward when in flood, and spreading thick deposits of fine sediment from far to the north across the flat landscape. Eventually the Euphrates and Tigris slid, as it were, to either side of the slowly rising mound of alluvium that formed along the central axis of the valley. The groundwater table grew higher and higher every kilometer downstream. As time passed, the saline and brackish lagoon of earlier times gradually became a huge expanse of freshwater marshes and lakes. Dense reedbeds trapped fine silt and helped maintain the flat terrain. A complex mosaic of estuaries, rivers, wetlands, and marshes gradually formed throughout much of what is now extreme southern Iraq. Between

3000 and 2000 B.C.E., extensive wetland areas formed along about two hundred kilometers of the rivers.

SUCH, THEN, WERE the sea level changes and climatic shifts that turned the Persian Gulf from a semiarid basin into a shallow waterway about a thousand kilometers long with a narrow entrance only thirty-nine kilometers wide in the Strait of Hormuz at the head of the Gulf of Oman in the northeastern Indian Ocean. Did hunting bands live in this challenging depression formed by low sea levels? Almost certainly there were at least narrow belts of wetlands and marshes close to the Ur-Schatt and on its floodplains by 10,000 B.C.E., which would have attracted small hunter-gatherer bands in such semiarid terrain. The river was a natural corridor from higher ground in northern Mesopotamia and the country on either side of the then-dry Gulf and in the low-lying basin itself. Around 8000 B.C.E., the Gulf was flooding rapidly as rising sea levels spread laterally from the river.

4

The sea level rise came as human life changed dramatically with the adoption of farming and herding by people who had hunted and foraged for wild plant foods for tens of thousands of years over a broad area of the Middle East. The new economies spread rapidly as wetter conditions returned around 8000 B.C.E. Small agricultural communities appeared over wide areas of southwestern Asia between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, and in the Gulf region—not that we know much about them. There are traces of small, transitory farming settlements, known mainly from stone tools, along the northeast coast of the Gulf. Tiny villages by the shores of now-dried-up lakes across the Arabian Peninsula date to between 7600 and 3500 B.C.E. By 5300 B.C.E., similar settlements also flourished at isolated spots along the Gulf’s western shore.

As far as we can tell, these people herded goats and sheep and relied on sporadic farming, foraging, and small game. At strategic locations along the coast, they also collected mollusks and caught fish and sea turtles. As early as 6000 B.C.E., we know that some farmers lived in the extreme south of what is now Iraq at the edges of, and within, what were becoming some of the richest, most biologically diverse environments on

earth. Since then, for more than five thousand years, humans have widened and dredged the marshes’ channels, irrigated fields, and built reed houses here, atop laboriously piled-up artificial islands of bundled reeds. These marshes were to become an anchor for the towns, cities, and irrigated landscapes that came into being in later millennia.

As recently as the 1950s, there were 15,500 square kilometers of marshes at the head of the Gulf. No one knows how extensive they were in earlier times. Those who have lived on the margins over the millennia have trodden hard on the dense marshland. Sumerian rulers hunted lions here, formidable prey shot into regional vanishment only during the twentieth century. Exiles, fugitives, and rebels sought sanctuary among the reeds. Assyrian king Sennacherib captured Babylon in 703 B.C.E. and pursued its Chaldean ruler, Merodach-Baladan, southward. Sennacherib “sent my warriors into the midst of the swamps and marshes and they searched for him for five days, but his hiding place was not found.” Nine years later, an expedition to Elam took Sennacherib’s ships to “the swamps at the mouth of the river, where the Euphrates empties its waters into the fearful sea.”

5

Upstream of the wetlands and marshes, the landscape gave way to arid terrain, where human settlement clustered near major watercourses and on levees and natural ridges that became islands when the floods came. The scale of the inundation varied greatly from one year to the next. The nearby marshes and wetlands with their abundant plants, wildlife, and fish served as anchors for many early farming communities, such foods being the insurance against crop failure when fast-running water swept away growing wheat and barley before being absorbed by the spongelike reeds and swamps of the lower delta. It was no coincidence that numerous farming villages and the earliest cities in what is commonly called Sumer flourished within a short distance of lush marshes. This completely different, life-sustaining environment assumed near-mythic proportions in the Sumerian world as a direct result of rising sea levels.

The marshes once formed tall palisades of reeds and narrow muddy channels, interspersed with great expanses of open water, rushes, and tangled sedge. Inconspicuous defiles would burst abruptly into lakes

with brilliant blue water, alive with swirling birds. I have never visited these marshes, but I know well the feeling of paddling kayaks along obscure defiles through dense reeds in other waterlogged landscapes, with only a swath of blue sky high overhead. The world feels secure, closed in, remote. The British traveler Wilfred Thesiger spent years living among the Marsh Arabs in the 1940s and 1950s when much of their traditional life still thrived. He described an environment of contrasts: “Sometimes the setting was winter, the water ice-cold under a chill wind sweeping across the Marshes from the far-off snows of Luristan. Sometimes it was summer, the air heavy with moisture, the tunnels at the bottom of the dark towering reeds where mosquitoes danced in hovering clouds, unbearably hot.”

6

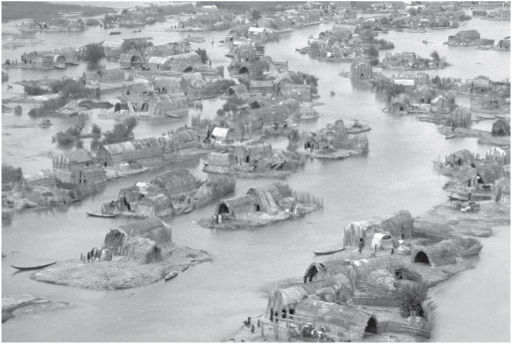

Figure 4.2

Aerial view of the Marsh Arab village of Saigal shows individual family compounds with houses made of reeds on small islands made from packed earth and reeds in southern Iraq where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers meet. Nik Wheeler/Flickr.com.

The diversity of plant foods, wildlife, fish, and birds in the marshes was remarkable. At least forty mammal species, including large wild pigs and an unusual water-dependent gerbil, flourished in and around the marshes. The bird life was extraordinary. Wrote journalist Gavin

Young after a visit in the 1950s: “The reeds we passed through trembles or crashed with hidden wildlife: otters, herons, coot, warblers, gaudy purple gallinule, pygmy cormorants, huge and dangerous wild pigs.”

7

Forty-two bird species bred in the marshes, which were also a major wintering area for birds from western Eurasia and as far away as western Siberia. The West Siberian-Caspian-Nile flyway is one of three major flyways in western Eurasia. At least sixty-eight water bird species and fifteen of birds of prey are known to have wintered in the wetlands. The marshes of the Euphrates and Tigris were a major staging point where migrants would pause to regain their strength and build fat before moving on. After spring, most of the birds are gone.

Then there were the reeds, perhaps the most important resource of all. The giant reeds with their tasseled tops resembled bamboos, their stalks so strong that boatmen used them to pole canoes fashioned from reed bundles coated with bitumen. In a largely treeless environment, reeds were a true foundation for human existence, which is why the god Marduk used reeds to fashion the first divine and human dwelling places. Most villages in recent times were patches of artificial islands adorned with matting houses. The same must have been true of ancient settlements, for there is no other way to live in such a waterlogged environment. Families decided how big they wanted their houses to be, then gathered huge piles of reeds, which they stomped into the water, having surrounded the house site with a reed fence.

8

Once the fibrous mound emerged above the surface, the fence joined the mound, followed by yet more reeds, or lenses of mud and reeds, firmly stamped down to form a compact mass. In the end the house mounds were virtually indestructible and often remained in use for generations. When the flood came, the owners simply added more reeds to the pile and kept abreast of the rising water. The houses themselves had bent rafters of reed bundles; neatly woven mats of the same material formed the roof and walls. Anywhere near the water, people could not live without reeds on the edge of or within marshes nourished by spring floods, which could raise water levels by up to three meters. As a Sumerian chronicle remarked, “Ever the river has risen and brought us the flood.” Then it adds, “All the lands were sea, then Eridu [Sumer’s oldest city] was born.”

9

One senses a complex

trajectory of history here: rising sea levels, then ponding of rivers and sediment once swept to the sea settling and forming not only desert but a marshy floodplain. And as part of the trajectory, farmers settled at the edges and within the marshes. Their remote descendants helped create a literate urban civilization.

TO SAY THAT rising sea levels created a civilization or that the Marsh Arabs of the twentieth century and their homeland are surviving mirrors of people and places of five thousand years ago is, of course, a woefully inadequate explanation of very complex events. Nevertheless, there can be no question that the expansion of the Persian Gulf played a decisive role in the first human settlement of what became Sumer. For generations, we archaeologists have argued that the first farmers colonized the delta from the north, bringing irrigation agriculture with them, perhaps around 6000 B.C.E. Perhaps, however, one can argue this a different way, with farmers following wetlands northward from the drowning Gulf, then settling on its margins near the great rivers or on humanly constructed mounds within the marshes once sea levels stabilized. Such a scenario is little more than intelligent guesswork. Excavation and survey within the waterlogged landscape is near impossible, and in any case, most farming villages of the day lie deep below river alluvium. Only occasionally do we get a glimpse of what life must have been like when sea levels were at their height and marshes tended to define life in the south. Almost invariably, these brief portraits come from the bases of long-occupied, ancient city mounds—some of the places where the gods were said to have cast reeds upon the ground and formed habitations.