The Attacking Ocean (6 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

FIFTEEN THOUSAND YEARS ago, the ice sheets that mantled parts of Britain and much of Scandinavia were in full retreat. The permafrosted arctic desert with its cold-tolerant herbs and shrubs that covered much of central and western Europe gave way to more wooded landscapes.

The constant winds carried seeds northward, as did birds and other migrating animals. Fifteen hundred years later, extensive birch, pine, and poplar forests covered Britain, northern Germany, and much of southern Scandinavia. By this time, rising sea levels had reduced Doggerland to a land of extensive coastlines and estuaries.

The rhythms of people’s lives changed to accommodate new realities.

9

Some of the greatest environmental changes occurred along northern Europe’s coastlines. Rising sea levels inundated continental shelves, filled estuaries, and turned many once rapidly flowing rivers into sluggish streams. The encroaching ocean created rich shoreline environments and wetlands, where fish and waterfowl abounded and shellfish could be gathered by the thousand. Plant foods like edible seaweed were often plentiful. Some of the richest of these low-lying coastal and estuarine environments lay in Doggerland and along the coasts of a large glacial lake that was to become the Baltic Sea.

As the Scandinavian ice sheet retreated, an ice lake had formed along its southern rim, dammed by low hills along what are now the north German and Polish coasts. When the weight of the ice lightened, the land rose faster than the sea. Cycles of cooling and warming changed the configuration of what was sometimes part of the ocean, at others a lake. After the Younger Dryas cold event ended in about 9500 B.C.E., renewed warming opened up an outlet through central Sweden, while a land bridge formed over what is now the Oresund between Denmark and Sweden. A brackish sea survived for about twenty-five hundred years before the rising land again turned it into another lake. Both were ancestors of the Baltic Sea. Around 5500 B.C.E., just as the North Sea flooded the last of Doggerland, the sea once again broke through and formed the direct ancestor of the modern brackish Baltic Sea.

10

The Baltic’s changing, dynamic landscapes proved to be a magnet for human settlement as early as 7000 B.C.E., perhaps earlier.

The fishermen stand motionless in the cold, shallow water, barbed spears poised at the ready. A man’s toes feel the mud, sense the imperceptible movements of a flounder on the bottom. A quick stab with the spear and a wriggling fish comes to the surface, firmly impaled on the

spear barbs. The fisher quickly wades ashore and kills his catch with a wooden club.

Doggerland’s low-lying shorelines with their creeks, sandbanks, and wetlands, and those of the Baltic, were a veritable garden of eden for the hunting bands that camped along northern coasts. They were fishers and fowlers, adept at collecting plant foods, falling back on shellfish when other foods were in short supply. Huge piles of discarded mollusks—shell middens—lie at strategic locations on Danish and Swedish coasts and must also lurk underwater in the North Sea. Food supplies were so abundant that populations rose steadily over many generations. Everyone dwelled at first in small encampments, shifting locations within hunting territories where there was plenty of room for everyone. Their possessions were the simplest, most of them fashioned from antler, bone, and wood, dugout canoes hollowed from logs with flint axes, wooden fishing spears, nets, and fish traps. Two weapons were all-important: the barbed fish spear, often with two or three antler or bone heads (like the Leman and Ower point) that impaled fish like pike or salmon with its prongs, and the bow and arrow. The hunters shot birds in flight with arrows tipped with tiny, lethally sharp stone tips. They also hunted deer and a formidable prey, the wild ox.

So plentiful were food supplies of all kinds that many bands lived within very circumscribed territories. But the richness of the Baltic environments must have paled beside those of Doggerland’s low-relief world of estuaries and marshes, low ridges, shallow valleys, and extensive wetlands. It was here, in a now-submerged world, that the densest hunting populations must have thrived, adjusting gradually to a radically changing world.

WHAT WAS DOGGERLAND really like? What varied landscapes once lay under the North Sea? A major breakthrough came when archaeologists Vincent Gaffney and Simon Fitch of Birmingham University dug into seismic data collected by the oil industry.

11

Oil exploration aimed at deep sediments, not at the shallow, much more geologically recent deposits

close to the seafloor where human artifacts might be found. Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS), a geophysical prospection company, generously gave the archaeologists access to six thousand square kilometers of seismic data from the Dogger Bank for a pilot study. Less than a month later, the shadowy course of a hitherto unknown river winding over the Dogger Bank for forty kilometers appeared on their computer screens. So successful were the preliminary results that PGS donated no less than twenty-three thousand square kilometers of three-dimensional seismic data from English territorial waters in the southern North Sea, a survey area slightly smaller than Belgium. A team of archaeologists, geologists, and palaeoenvironmentalists spent eighteen months exploring an unknown prehistoric land.

The seismic data provided information on rivers, estuaries, and lakes, as well as salt marshes and coastlines. The research located about sixteen hundred kilometers of river channels and twenty-four lakes or marshes, the largest of which covered more than three hundred square kilometers. This was a very watery landscape. At its heart lay an immense bathymetric depression known today as the Outer Silver Pit, perhaps an estuary or lake off the Dogger Bank, which has been mapped over seventeen hundred square kilometers. Great sandbanks at the eastern end hint that it eventually became an estuary for two major rivers or channels entering from the east and southeast. As sea levels rose, the river mouths may have become marshes, one of which, an extensive salt marsh, must have been a major resource for local hunters, with its abundant fish, bird, and plant life.

At least three rivers flowed from the slightly higher ground that is now the Dogger Bank. They meandered through wide valleys, fed by numerous small streams. Judging from what we know about contemporary valleys on higher ground, watercourses large and small flowed through a network of channels quite unlike the more well-regulated course of the Thames or Rhine Rivers of today. The channels were unstable, changing constantly with sudden floods and course shifts that helped form mazes of back channels, creeks, and swamps.

It was a monotonous, water-filled landscape, one might think, but to the hunting bands who lived there, the environment would offer rich potential and all kinds of subtle landmarks for finding one’s way around. An outcrop of white sand, a clump of trees overhanging a small pond, deep reedbeds where a hunting platform could remain undetected—all were inconspicuous markers. So were shallow lakes where a hunter could wear a decoy headdress, swim quietly among sitting ducks, and pluck them from below the surface. Deer, pigs, and numerous small mammals, and also myriad waterfowl, congregated along riverbanks, by lakes, and in marshes. Fish must have dominated many diets. Salmon runs alone would have sustained some bands for months on end. Plant resources were plentiful—not only with reeds to make baskets, fish traps, and huts, but also as food sources with a broad range of seasonal berries and fruit, hazelnuts, and acorns as forest spread across the landscape. Each family, each group, would have passed knowledge of the food supplies that changed from season to season from one generation to the next in an endless mnemonic that mapped the landscape across hunting territories large and small.

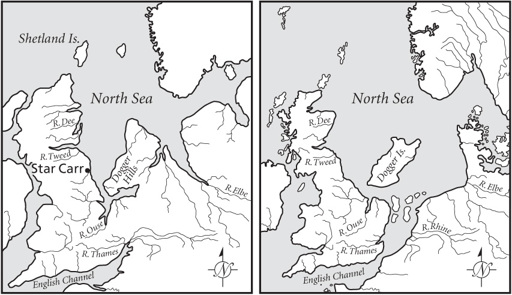

Figure 2.2

The main features of Doggerland ca. 10,000 years ago (left) and ca. 6,500 years ago (right).

Unfortunately, seismic data doesn’t provide information on archaeological sites, which are inaccessible far below sea level. Gaffney and his colleagues have ranked various features located in Doggerland as to their potential for archaeological discovery. Highest ranked, as one

would expect from experience with sites on higher ground, are lake and marsh areas, also coasts. One day a detailed map might provide enough information for a more thorough exploration of the landscape by ships using core borers to sample subsurface deposits in the hope they will yield proxy traces of human activity, such as pollen grains documenting deliberate forest clearance or humanly set fires to foster new growth. Meanwhile, we have to extrapolate from known sites on higher ground.

IN ABOUT 8500 B.C.E., a hunting band camped on the shores of a small glacial lake in what is now northeastern England. Dense reedbeds surrounded the water; birch woodland pressed to water’s edge. The resulting waterlogged archaeological site, known as Star Carr, preserves an unusually fine-grained chronicle of hunter-gatherer life in a landscape that must also have flourished in Doggerland, close to the east. Grahame Clark of Leman and Ower fame excavated Star Carr between 1949 and 1951.

12

He wrote of a small winter hunting platform deep in lakeside reeds used by red deer hunters. Clark described a remarkable series of bone and wooden tools, including elk antler mattock heads (one with the tip of its wooden handle still in place), a wooden canoe paddle, awls, and even bark rolls and lumps of moss used for fire lighting. Several excavators have returned to Star Carr since Clark’s day, using all the resources of today’s high-tech archaeology to reinterpret the site.

Clark had focused on the waterlogged portions of the site. A new generation of researchers has traced drier areas of Star Carr and revealed what was actually a far larger settlement that once extended over some 120 meters of the shoreline. By dating minute charcoal particles, researcher Petra Dark was able to show that the inhabitants had burnt off the reeds repeatedly, perhaps to provide a better view of the lake and surrounding terrain, and also a good canoe-landing place. Such repeated burnings occurred for some 130 years. There was then a century with no burning, followed by another eight decades of more firing. Star Carr’s hunters took many ten-to eleven-month-old deer, which would have been killed between March and April. Reed samples and aspen buds also date

to the same time of year, with Star Carr being occupied between March and June or July each year. Recent excavations have revealed a circular house with at least eighteen wooden posts and a sunken floor that was 3.5 meters wide, and also a wooden platform made of split and hewn timbers. This substantial dwelling may reflect more permanent settlement than is often assumed for the hunters of 10,500 years ago. Whether there were similar important, and repeatedly visited, locations like Star Carr in Doggerland is of course unknown. But there is no reason why there should not have been, for environmental conditions were much the same over a vast area of what is now the southern North Sea.

THE SOFT

SCRAPE, SCRAPE

sound of flint scrapers cleaning a pegged-out deerskin would have greeted a visitor to a Doggerland hunting camp in 7000 B.C.E. In this cold, often rainy world, skin cloaks and fur garments were essential for young and old. Like all hunters, the women would have made use of a variety of skins for different garments, perhaps tough seal hide for boots, soft rabbit fur for decoration and baby clothes. A small cluster of grass huts, perhaps a central hearth, dogs, children, and a smell of decaying fish—the scene would have been the same at dozens of such camps. Weeks, even months, could go by without the band seeing anyone else. If they did, it was probably an event, a matter of a cautious approach and careful exploration of potential kin relationships. The population of Doggerland would never have been large, dwarfed by a seemingly endless world of dunes, lakes, wetlands, and woodland. You would have glimpsed humans but rarely, usually on slightly higher, better-drained ground, or camped among reeds or by lakes or rivers. A wisp of woodsmoke from a hearth, the soft chipping sound of a stone adze carving a dugout canoe, women scraping a deerskin pegged out on damp ground: Your impressions would have been fleeting, dwarfed by the marshy landscape. In a few locations, dark smoke would rise from dry reedbeds in spring, as the hunters set fire to undergrowth to gain better access to lakes and streams, and to foster new plant growth for game.