The Ball (9 page)

Authors: John Fox

Illustration of racket and ball production, from Garsault's

Art du Palmier-Raquetier

, 1767.

Finally, he pulled out a roll of familiar optic-yellow wool felt and cut two long strips, which he tacked onto the ball to hold them in place. He then began to trim the edges into rounded forms that would neatly cover the ball's surface. Once he'd achieved the right shapes he went on to sew the ball's cover together with needle and thread, making sure the felt was tight and even all around.

“There we go!” he declared triumphantly as he tossed the finished ball to me. All told, it had taken him 45 minutes to make a single ball. The finished ball I held in my hand was slightly smaller and about 25 percent heavier than a lawn tennis ball.

“Do you mind if I keep this one as a souvenir?” I asked.

Matty's face took on a look of visible pain as he stared silently at the fruit of his hard labor in my greedy hand. “Well . . .”

“You know what, never mind,” I said, immediately embarrassed.

“It's just that it takes so bloody long to make one and, to be honest, we sell these to the public for twenty euros each.”

He plucked the shiny new ball out of my hand and reached into his discard basket. “Would you be okay with an old one?”

I took the gift happily, embarrassed by what would surely not be my last breach of real tennis etiquette. Matty grabbed two rackets out of the corner of his office. “That's enough work for one day. Shall we play?”

T

he

jeu de paume

court at Fontainebleau is a spectacular, cavernous space, the largest real tennis court in the world (there's very little standardization in the size of real tennis courts). The stone construction of the court's outer walls gives it the damp, echoing feel of a medieval castle's great hall. The original tennis court was built here by Henry IV in 1600 along with a second outdoor one of which only traces remain. When “good king Henry,” one of France's most popular kings, wasn't granting religious liberties to the Protestants or guaranteeing a “chicken in the pot” for every commoner, he was known to relax with a spirited game of

paume

. In fact, he loved tennis so much that after narrowly surviving the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572, in which thousands of Protestants perished in Paris at the hands of rioting mobs, he rose first thing the next morning to continue a tennis match he'd started the day before.

Henry's court burned down in 1701 but was rebuilt from the original walls in 1732. Napoleon restored the court in 1812. Then, during World War I it was put to use as a recovery ward for wounded soldiers and later became a concert hall before being reinaugurated as a tennis court in 1981.

As I stepped out on the court, which as recently as 1991 was still surfaced with the original Normandy limestone tiles, I could almost picture Marie Antoinette cheering on Louis XVI from the gallery. Or Cardinal Richelieu coaching Louis XIII on his forehand. A total of eight French monarchs had played on this court. Now it was my turn.

I felt honored to be learning the particulars of real tennis from a player of the Ronaldson pedigree who, by his own estimate, would be ranked around 20 in the worldâthat is, if the sport had a proper ranking system. Despite being among the elite players on the planet, Matty complained that it didn't mean much in a sport as obscure as his. And, worst of all for a young single guy, it didn't get him very far with the girls.

“I was with another player recently, chatting up some girls at a pub. When we told them we were among the top real tennis pros in the world and then had to explain what real tennis is, you could just see their eyes glazing over.”

He handed me a racket, and for a second I thought he was having a good laugh at my expense. It looked like a relic of an earlier age, the kind of antique racket you might pick up at a country flea market and hang on your wall next to, say, your coat of armor. It was long, wooden, and incredibly heavy, with a tiny head and an unforgivably small sweet spotâwhat in lawn tennis would count as five excellent reasons to upgrade to a better racket.

This was no joke, however. The rules of real tennis require that rackets be made “almost entirely of wood.” The heavy weight is required to handle the heavier balls and the head is kept small to allow for extremely tight strings. Most unusually, the racket head is curved slightly up from the handle like the blade of a hockey stick to make it easier to hit balls close to the floor or scoop them out of corners.

Matty held out his right hand. “If you look at the racket, it's shaped like a hand. Since the game started out with just the palm of the hand, when they got around to making rackets they modeled them after the anatomy of the hand.”

The racket I held in my hand was made, like most real tennis rackets, by Grays of Cambridge, England, a five-generation family business that's had a virtual monopoly on the industry since 1885. Four long-term employees handcraft each racket from willow staves and loops of ash and, in a rare concession to modernity, strengthen and make it rigid by adding up to three layers of a vulcanized fiber. The fiber performs like graphite but is actually made from paper, which means almost the entire racket, in accordance with regulation, is made from wood or wood products.

When the racket was first introduced to the game of tennis in the 16th century, it wasn't immediately seen by all as such a great advance. In the first account to mention the racket in 1505, King Philip of Castile played a match at Windsor Castle against the marquis of Dorset while King Henry VII of England watched. The marquis used only his hand while Philip used a racket, so Philip took a one-point handicap. In another account written by the Dutch scholar Erasmus, one player suggests to the other that they employ rackets: “We shall sweat less if we play with the racket,” he argued. But his opponent, either a purist or a glutton for punishment, had no time for such newfangled inventions. “Let us leave the nets to fishermen; the game is prettier if played with the hands.”

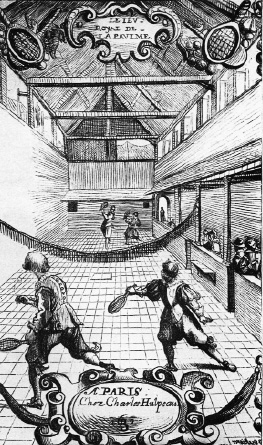

Jeu de paume

in a royal Paris court, 1632, and at Fontainebleau, 2009.

We took our positions at either end of the enclosed court. Though they vary in dimensions, all real tennis courts have the same layout and are both wider (about 32 feet) and longer (about 96 feet) than a lawn tennis court. The lofty ceiling at Fontainebleau is 35 feet high, tall enough to allow all but the highest lob shots. The features of the court unmistakably resemble the medieval cloister they're based on. Three sides of the court have sloping roofs, known as penthouses, below which are netted galleries from which spectators can watch the game.

Unlike lawn tennis, there is a service end and a receiving, or hazard, end, and each has different features and means of scoring points. Having been forced to play lawn tennis by my mother as a kid, I was hopeful I could hold my own or at least keep from embarrassing myself. Matty's first serve was a slice serve that, as required by the rules, bounced off the penthouse on my end before crumpling up and dying against the back wall.

I stood there helplessly looking at the little cork-stuffed ball still wedged into the corner of the court, appreciating like never before what the introduction of rubber did for the world of sport.

“That ball didn't bounce at all!” I whined.

Matty was clearly enjoying this. “Sorry, I served it with enough backspin that it never got out of the corner.”

15âlove.

Unlike lawn tennis, where a hard-hit topspin kicks the ball up and out of the back court, making it hard to return, in real tennis it's the opposite. Topspin brings the ball high off the back wall and gives your opponent an easy opportunity to smash it back and score a point. Real tennis is all about the backspin, all about killing what absurdly little bounce there is in the ball in the first place.

He served again. This time the ball didn't so much bounce as roll off the side penthouse and around to the back. I readied my racket for a forehand return only to see the ball roll behind me and over to my backhand. I tied myself in knots trying to spin the heavy racket around to the other side in time, but it was too late.

30âlove, and I'd yet to touch the ball.

Matty served for a third time and this time I was paying more attention to the ball's trajectory. I caught it off the back wall with a decent, if slightly shaky, backhand. He snapped the ball back to my left again. I pulled back early, ready to swing when suddenly the ball changed course, now moving sideways across the court and nowhere near my racket.

“Ha! I got the

tambour

,” he declared cheerily. “You see, you thought you knew where the ball was going, and suddenly it was in a corridor of uncertainty.”

From my own experience, I was quite used to dealing with base paths, alleys, sidelines, and baselines but I wasn't sure I was up for playing a sport that involved “corridors of uncertainty.” Matty had quite artfully and intentionally placed the ball into an inconveniently angled buttress that protrudes into the service end of the court, just as the flying buttress would have in a medieval courtyard.

40âlove.

B

efore going any further in describing my utter humiliation at Matty's hands, I should address one of the most obvious mysteries in this strange game of tennis. It's a question that seems to have kept etymologists busy for the past century. One has argued for the game's Arabic origins, claiming that its name refers to the ancient sunken city of Tinnis in the Nile Delta; it was famous for its fabrics, which, he guessed, could have been used to stuff balls. Good try.

Another speculated that it derived from the old German word for a threshing floor,

tenni

, which may have at times doubled as a tennis court. Yet another thought it was an English word that came from an early version of the game played with ten players. And so on.

It turns out, however, that the word “tennis,” like everything else about the game, has French roots and derives from

tenez

, which means “take heed.” This was what the server once called out to warn his opponent as he put the ball in play. Although French in origin, the word first appeared in Italy in 1324 in a strange account of 500 French cavaliers, “all noblemen and great barons,” who arrived in Florence one day with their fancy French game (not realizing, apparently, that Italians couldn't care less about tennis and were quite content playing football for the rest of history). An Italian priest, the account states, “played all day with them at ball, and at this time was the beginning in these parts of playing at tenes.”

So that's the word tennis. Now what about the bizarre scoring system that assigns 15 points instead of one and “love” instead of zero? Leave it to the French once again. Most scholars (though debate rages in esoteric tennis history circles) agree that it comes from the French

l'oeuf

, meaning “egg” (which, if you think about it, closely approximates the number zero). Over time, the English bastardized the termâas they tend to doâinto “love” and we've never looked back or asked whether zero might not make more sense.

As for a scoring system that assigns 15 points for winning one measly shot, it appears that people were already scratching their heads over this one as early as 1415. Unable to find a logical explanation for the peculiar system in the here and now, one writer of the time turned to God and the afterlife: “In much the same way as a tennis player wins fifteen points for a single stroke, those who support and further righteousness and justice are also awarded fifteen times or more than normal for their good deed.”

The true answer, scholars have determined, is far less noble and has to do with a practice that's been inseparable from sport since ancient times: gambling. Betting was standard practice in tennis matches for most of the game's history. As the historian Heinrich Gillmeister has documented in his study of tennis, judging by the king's own accounting book, poor Henry VII of England was about as versed in the game as I am: