The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (21 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

An early historian of Chapman's Battery left an apt and accurate description of the battle: “The battle of Dry Creek was one of the hottest, for the numbers engaged, of the war. It was claimed at the time by the Federals to be a drawn battle, but its effect was to turn back Averell's army and preserve for many months a large scope of valuable territory from the devastations of Yankee invasion.”

426

Chapman's gunners, in particular, deserved accolades. The Confederate artilleryâoften inconsistent in performanceâfought long and hard at White Sulphur Springs. Major William McLaughlin, Sam Jones's chief of artillery, praised them in his report of the battle. “The men of the battery stood bravely and steadily by their guns, though subjected to a steady, hot, and well-directed fire from the enemy's guns,” he declared, “and too much credit cannot be awarded to Captain Chapman for the zeal, gallantry, and energy displayed by him throughout the engagement.”

427

To a man, Patton's regimental commanders praised the efforts of their units. Their stout stand had stopped Averell's raid about a dozen miles short of its objective and had saved the law library from capture. In the process, they inflicted heavy losses on the Fourth Separate Brigade. “Notwithstanding the great disadvantages under which they labored, the officers and men acted most nobly, repelling the oft-repeated and daring attempts of the enemy to dislodge them,” reported Major R. Augustus Bailey of the 22

nd

Virginia Infantry in a good example of the sort of encomia heaped out on the Confederate soldiers. “The commanders of companies and their subaltern officers are entitled to much praise for their coolness under fire and the tenacity with which they held their ground.”

428

A Virginia newspaper sounded a similar note: “All our troops behaved most gallantly, showing great coolness, courage, and power of endurance.”

429

Fielding R. Cornett of Company C of the 8

th

Virginia Cavalry summed up the role played by the First Brigade in just a few words. “They made ten different charges on our lines,” he proudly wrote to his sweetheart, “and would get [with]in ten steps of our men, but were repulsed every time.”

430

Such was the nature of the brutal two-day slugging match at White Sulphur Springs.

Patton likewise had every reason to be proud of the performance of his men. “During the engagement I repulsed eight separate and distinct charges of the enemy, besides frequent engagements with his skirmishers,” reported Colonel William H. Browne of the 45

th

Virginia Infantry, who heaped praise on his hard-pressed regiment. “In a majority of these charges the enemy came within the distance of fifteen or twenty paces of my line, and I am well satisfied I did him great damage, capturing some, killing and wounding large numbers. Notwithstanding the long marches my men had made (having marched about 100 miles during the four days preceding the engagement), I had no stragglers or skulkers. I have never on any battlefield seen men act cooler or braver; they fought with a determination to do or die.”

431

These men were all Virginians, and they had sworn their allegiance to the Confederate government at Richmond. Their home countyâGreenbrier Countyâwas about to break off from the Commonwealth of Virginia as part of the new state of West Virginia, and they were determined to do anything that they could to prevent that from happening. They were mostly farmers, merchants and students who had enlisted in counties that eventually made up West Virginia. They had no choice in the formation of the new state, and they did not favor it. They strongly believed in the cause of secession, and they were willing to die for a cause that they fervently believed in. Hence, they had an extra incentive to fight hard at White Sulphur Springs, and fight hard they did.

At White Sulphur Springs, George Patton proved to be an able battlefield tactician capable of performing well in independent command. He used his troops well, timely and effectively shifting them to meet threats as they developed. He used his artillery judiciously and efficiently and made outstanding use of difficult terrain that favored the positions held by the enemy. By so doing, he demonstrated that he was a worthy successor to Brigadier General John Echols, whose ongoing health problems forced him to leave the army shortly after the May 5, 1864 Battle of New Market.

432

Echols heartily endorsed Patton's promotion to brigadier general. He called Patton “energetic, ardent and most effectiveâ¦prompt, vigilant & highly intelligent, possessing the confidence and affection of his menâ¦a gentleman of high order of accomplishment.”

433

Echols's departure made it possible for Patton to become the permanent commander of the First Brigade. His superiors recommended him for promotion to brigadier general in December 1863 as a result of the combination of Echols's ongoing health problems and Patton's fine performance at White Sulphur Springs. However, the Confederate Senate never confirmed the promotion, and he remained a colonel for what remained of his life.

434

Patton was low key about his role in winning the battle. “I was in command of our forces during the fight and was fortunate enough to escape unhurt,” was all he said about it in a letter to a friend a few weeks later.

435

However, George Patton had just over a year to liveâhe was mortally wounded in action at the September 19, 1864 Third Battle of Winchesterâand he remained in command of the First Brigade until his death. During that time, he and his old friend Averell tangled several more times with mixed results. Of course, George S. Patton's greatest legacy was his grandson and namesake, General George S. Patton Jr., who led the Third Army to victory in the European Theater of Operations during World War II.

More important, Patton's defeat of Averell's thrust toward Lewisburg had considerable strategic consequences. During the entirety of Averell's great law book raid, Major General William S. Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland was in the midst of its brilliant campaign to take the vital rail hub of Chattanooga, which fell to Rosecrans on September 9, just over a week after Averell's raid ended. The fall of Chattanooga so alarmed the Confederate high command that Lieutenant General James Longstreet's First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, was sent to reinforce General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee, stripping Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia of a significant portion of its hardened core of veteran soldiers.

436

Burnside's army forayed into east Tennessee both to secure the territory for the Union loyalists who made up the bulk of that region's population and to tie up Jones's troops and prevent them from being used to further reinforce Bragg's army. Indeed, Burnside intended to recruit and arm additional troops in the area, further enlarging his army.

437

Had Averell defeated Patton and pushed on to Lewisburg, Jones would not have been able to shift his focus from Averell's threat from the east to the threat posed by Burnside's army's approach from the west, and his command would have been badly squeezed. Hence, Patton's victory at White Sulphur Springs had significant strategic consequences for the defense of east Tennessee and also for what soon became known as the Chickamauga Campaign.

At the same time, the lackluster Confederate pursuit of the Fourth Separate Brigade left a lot to be desired. Writing a few days after Averell escaped, General Robert E. Lee penned a letter to gently chastise Brigadier General John D. Imboden. “I regret exceedingly that the enemy escaped with so little damage to himself,” he began. “It seems to me the command of Averell should have been more severely punished. Unless we are active in inflicting all the loss we can upon the parties sent on these expeditions, and in using every opportunity of cutting them off, they will continue to be sent out, will desolate the country, and bring great distress upon the people.” Lee concluded, “I hope you will be more successful in the future.”

438

Lee's assessment was spot on, and with his gentle chiding, he correctly pointed out that a great opportunity to corral and destroy the Fourth Separate Brigade had slipped away, largely due to the lackluster pursuit executed by Mudwall Jackson, Jenkins's Brigade and Corns's 8

th

Virginia. Imboden's Brigade was probably too far away to have had much of an opportunity to cut off or otherwise hinder the escape of Averell's command. Nevertheless, Lee was correctâan opportunity to punish the Yankee horse soldiers slipped away due to bungling by Jones's subordinates.

Indeed, his ineffective and inefficient efforts to stop Averell on the way to White Sulphur Springs and his even more ineffective efforts to pursue Averell earned Jackson the unflattering moniker of Mudwall. While pursuing Averell through Huntersville, his troopers found “Mudwall Jackson” scrawled on the walls of the old county courthouse, “the principal feature of which was a complaint that âMudwall Jackson' would not fight,” as Confederate soldier John McNeel reported. McNeel saw this graffiti a few days after Averell's men evacuated Huntersville, “and it was understood by the Confederate soldiers as having been put there by a Yankee soldier, and as we Confederates understood it at the time, the animus of the verse was because the dead âStonewall' had been so hard on the Yankees, and the live âMudwall' had escaped their net.”

439

The many deficiencies of Jackson's command, which thwarted its efforts to hinder Averell's advance or to catch up to his retreat, made their commander something of a laughingstock. Jackson carried that unhappy nickname for the rest of the war.

440

Further, Averell conducted his command and the battle well both on the battlefield and during the retreat. His brigade was outnumbered by a large margin, and his men went into battle with an extremely limited supply of ammunition. He used his troops well, was judicious in his use of his limited supply of ammunition and was definitely the aggressor throughout the fight, somewhat uncharacteristically for the normally conservative New Yorker. However, his desire to either wait out Patton or wait for the arrival of Scammon's infantrymen cost his command. “We remained twelve hours longer at Rocky Gap than was necessary, expecting an operation from the Kanawha valley, but it did not come,” Captain Francis Mathers of the 8

th

West Virginia observed.

441

At the same time, Averell's withdrawal under fireâalways difficult under even the best of circumstancesâwas conducted brilliantly. His planning for the retreat was impeccable, and the execution of his plan was flawless. The barricading of the road made an aggressive pursuit by the outnumbered Confederate cavalry almost impossible, and the use of those barricades bought him sufficient time to safely conduct his entire command to Beverly without any significant exposure to enemy forces. His retreat was a masterpiece, and he deserves a great deal of credit for extracting his command intact while low on ammunition and deep in hostile territory.

Averell took a raw, undisciplined command and turned it into a powerful and effective fighting force in a short period of time. Just a few months earlier, Major Theodore F. Lang of the 3

rd

West Virginia had described the Fourth Separate Brigade as consisting of “loyal, courageous fighters, scattered through half a dozen counties, but who knew little of discipline, or of regimental or brigade maneuversâscantily supplied with approved arms, equipment, clothing, etc.” Lang also observed that these men “were inefficient for any reliable defense of the country, and the often hopelessness of any effort to take the offense.” He had concluded with the damning statement, “All of the officers and enlisted men alike were war students with no teachers among them of skilled warfare.” Within eighty days of taking command of the Fourth Separate Brigade, Averell had crafted “a splendid brigade out of the best quality of raw material” and had mounted the men, trained them and made them into a raiding and fighting force to be reckoned with for the rest of the war.

442

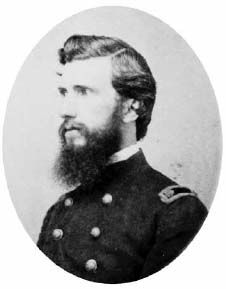

Major Theodore F. Lang of the 3

rd

West Virginia. Lang later documented the role of loyal West Virginians in the Civil War.

Ronnie Tront

.

Not long after Averell's repulse at White Sulphur Springs, the Confederate authorities wisely evacuated the law library from Lewisburg and sent it on to Richmond, thereby removing any further incentives for the Union high command to launch another raid to seize it.

443

Nevertheless, Lewisburg remained in the Union bull's-eye. In November 1863, Averell launched another long raid to destroy or damage the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in the vicinity of Lynchburg or Dublin. This long raid passed through White Sulphur Springs and Lewisburg and culminated in a battlefield victory for Averell over Echols's brigadeâthe same brigade that had defeated his troops at White Sulphur Springsâin the November 6 Battle of Droop Mountain.

444

According to Patton family legend, while on the way to Droop Mountain, Averell detailed a sergeant to guard the Patton family and stopped to visit Sue Patton and her children at the family's residence in Lewisburg.

445