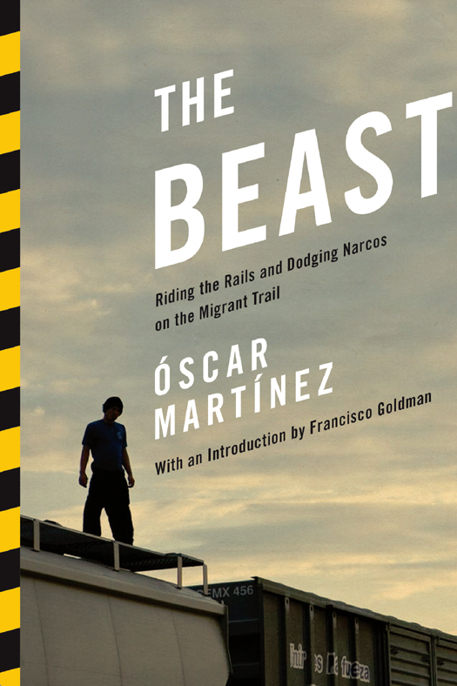

The Beast

Authors: Oscar Martinez

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2013

Translation © Daniela Maria Ugaz and John Washington 2013

First published as

Los migrantes que no importan

© Icaria Editorial 2010

Foreword © Francisco Goldman 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-132-9

eISBN (US): 978-1-78168-190-9

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-502-0

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martínez, Óscar (Oscar Enrique)

[Migrantes que no importan. English]

The beast : riding the rails and dodging narcos on the

migrant trail / by Óscar Martínez; translated by

Daniela Maria Ugaz and John Washington.

pages cm

“First published as Los migrantes que no importan

[copyrighted] Icaria Editorial 2010.”

ISBN 978-1-78168-132-9 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. Illegal aliens—Mexico. 2. Central Americans—

Mexico. 3. Immigrants—Mexico. 4. Mexico—

Emigration and immigration—Social aspects.

5. Central America—Emigration and immigration—

Social aspects. I. Title.

JV7402.M3713 2013

305.9>069120972—dc23

2013020580

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

by Francisco Goldman

Chapter 1. On the Road: Oaxaca

Chapter 2. Here They Rape, There They Kill: Chiapas

Chapter 3.

La Bestia

: Oaxaca and Veracruz

Chapter 4. The Invisible Slaves: Chiapas

Chapter 5. Kidnappings Don’t Matter: Veracruz, Tabasco, Oaxaca

Chapter 6. We Are Los Zetas: Tabasco

Photo Insert

Chapter 7. Living among Coyotes: To the Rio Grande and Back

Chapter 8. You Are Not Welcome in Tijuana: Baja California

Chapter 9. The Funnel Effect: Baja California and Sonora

Chapter 10. The Narco Demand: Arizona

Chapter 11. Cat and Mouse with the Border Patrol: Arizona

Chapter 12. Ghost Town: Chihuahua

Chapter 13. Juárez, Forbidden City: Chihuahua

Chapter 14. Dying in the Rio Grande: Tamaulipas

Foreword

By Francisco Goldman

ElFaro.net

advertises itself as Latin America’s first online digital newspaper. It is based in El Salvador, and was founded in 1998. Many enterprises nowadays, individual and collective, proclaim themselves or would like to be considered “alternative,” and as part of a “vanguard” showing the way forward, but

ElFaro.net

truly is both. It certainly offers an alternative to the kinds of fare provided by El Salvador’s familiar newspapers—complicit with the political and moneyed establishment, and thoroughly mediocre at best, as is true of the establishment press and other media throughout Latin America. And

ElFaro.net

is a vanguard because it is so very excellent in every way that it has become a beacon of the possible, of the ambitious, of the truly revolutionary, to young journalists up and down the continent. To the question of how it can be that the Bloomsbury of Latin American journalists has sprung up in tiny El Salvador and not in Mexico City or Buenos Aires, one answer is, Why not? and another is, Actually, it makes perfect sense, and yet another is, Isn’t this just what the digital age promised? No more periphery, the center is everywhere. Except it takes a visionary editorial team, and exceptionally courageous and talented journalist-writers, to fulfill such an idealized and wishful supposition.

ElFaro.net

was founded in 1999, six years after the end of El Salvador’s civil war, by two young Salvadorans who’d been raised abroad, the sons of political exiles. When they returned home to their war-devastated country, and found it still as violent or even

more violent than before, saturated by organized crime and gangs, the infamously sadistic

maras

, terrorizing poor urban neighborhoods and towns, they decided that there really could be such a thing as cutting-edge journalism, and that it should and could make a difference. And what is cutting-edge journalism? It means writing about what nobody else dares to write about, at least not thoroughly or memorably, and getting as close to your subjects as you can, and taking as much time as you need, and then somehow knowing how to write the hell out of what you find—capturing

mareros

’s ways of speaking, their jargon and gestures, as if the writer himself has been a

marero

all his life, deciphering their codes, prising from them their life-stories, their secrets, their most scarifying and gruesome stories, their odd vulnerabilities, learning the layout and nuances of their places, and doing the same with their rivals, their victims, with the police and prosecutors who pursue them, and shaping that material into compelling narratives that engross the reader and deliver much larger and more unsettling meanings than those found in ordinary newspaper dispatches. I hadn’t read stories like those published in

ElFaro.net

anywhere else. Such high-quality and important work doesn’t go unnoticed, and the digital newspaper’s writers have gathered some of the world’s most prestigious journalism awards: cofounder Carlos Dada, the current editor, won the Maria Moors Cabot Prize, and Carlos Martínez won the Ortega y Gasset Award.

Now Carlos’s brother, Óscar Martínez, has produced

The Beast

(originally

Los migrantes que no importan

, “the migrants who don’t matter”), about the Central American migrants who trek across Mexico to reach the northern border and the United States. With mind-boggling courage and commitment, Óscar Martínez went where no other journalist from Mexico or elsewhere had gone, exploring the migrants’ routes, in a series of trips, from bottom to top, that take in not only the infamous train known as “La Bestia”—he rode on that train eight times—but also the desolate byways traveled on foot where the very worst things happen. Despite being a compilation of dispatches published over two

years in

ElFaro.net

, the book has the organic coherence, development, and narrative drive of a novel. It reads like a series of pilgrims’ tales about a journey through hell. (Even calling it hell feels like an understatement.)

The Beast

is, along with Katherine Boo’s

Behind the Beautiful Forevers

, the most impressive nonfiction book I’ve read in years. I first read it in Spanish a couple of years ago after it was recommended to me by Alma Guillermoprieto, in an edition published in 2010 by Icaria, a small press in Barcelona. In Mexico and Latin America, the book might as well have not existed. How could it be that this book, which should be urgent reading for all Mexicans at all interested in what occurs in their country, was not immediately published in Mexico? Perhaps because it holds up a mirror to a Mexico almost too depraved, grotesque, and heartless to believe. In different ways it holds up just as painful a mirror to the United States, and another to Central America. Finally

The Beast

was rescued and published, in late 2012, by the Oaxaca-based Sur + Ediciones, one of a handful of excellent small presses in Mexico that have reinvigorated the country’s literary landscape. Thanks to their initiative the book was discovered by Verso, which has brought out the present edition in English.

Over the last few months, I’ve had many conversations with people who’ve read the book, which I urge upon everybody I meet. They always speak, of course, about the importance of what it conveys, and in awed tones about its author’s courage. And then they always add, “But how come that

cabrón

writes so well!” Though only in his mid-twenties when he wrote the book, Óscar Martínez writes really, really well, with liveliness, precision, vividly observed detail, with a restraint which it must have been terribly difficult to sustain considering the rage he often felt over what he was witnessing, with astonishing and never superfluous poetry and, most of all, with a genius for conveying human character. Martínez’s literary gift is what lifts

The Beast

into a work that delivers much more than journalistic information—though its information is of pressing and illuminating importance—and

makes it a masterpiece. Each chapter narrates a unique story. At times the book reminded me of Isaac Babel’s

Red Army Tales

.

“ ‘I’m running,” Auner says, his head ducked down, not meeting my eyes, ‘so I don’t get killed.’ ”

So begins the first pilgrim’s tale, in a migrant shelter in southern Oaxaca where Martínez meets Auner and his two Salvadoran brothers, embarking on the journey north without any set plan, without knowledge of its dangers, traps, and rules. Yet it’s all-important to know what you’re doing on this journey, the book will teach us, again and again: it should be required reading for any migrant setting out across Mexico. Along the way only these widely scattered migrants’ shelters, most run by the Catholic Church, offer some respite from the hardship and unyielding fear of the journey, though not entirely—because the shelters are also infiltrated by spies working for the Zetas cartel and other criminal groups, or corrupt coyotes who prey on the migrants.

The first time I asked him, though, he told me he was migrating to try his luck. He said he was only looking for a better life,

una vida mejor

, which is a common saying on the migrant trails. But here in southern Mexico, now that Auner and I are alone, with the train tracks next to us and a cigarette resting between his lips, now that we’re apart from his two younger brothers who are playing cards in the migrant shelter’s common room, he admits that the better word to describe his journey is not migration, but escape.

“And will you come back?” I ask him.

“No,” he says, still looking at the ground. “Never.”

“So you’re giving up your country?”

“Yeah.”

The brothers’ lives have been threatened, but they don’t know by whom. At home their mother was killed by gang assassins, perhaps in reprisal for one of the brothers having witnessed and denounced the murder by drunks of a friend who was a gang member, or perhaps it was because their mother witnessed a gang

assassination outsider her little store. “Death isn’t simple in El Salvador,” Martínez writes. “It’s like a sea: you’re subject to its depths, its creatures, its darkness. Was it the cold that did it, the waves, a shark? A drunk, a gangster, a witch?” Many migrants head north to flee the economic devastation of their countries, the paucity of decent work or pay, in search of “a better life” in the United States: good wages, the chance to send money back to their families, to save enough to build a home or start a small business when they return. But Óscar Martínez also introduces us to many people who are fleeing out of fear. A young gang member running for his life because the rival gang has conquered his gang’s turf and had he stayed, his death at their hands would have been assured. A policewoman fleeing because her two successive police husbands had been murdered, and, while she was in mortal danger too, she feared even more being no longer able to endure her dread and despair and turning her own pistol on herself and her baby daughter. Orphaned girls in their early teens, fleeing homes where stepparents, stepbrothers or other informal guardians regularly rape them or violently enslave them.

All are in flight from fear, only to exchange it for the different, unrelenting fear they will discover and learn to endure on the journeys north, with little chance, increasingly little chance, we learn in

The Beast

, of ever actually reaching the United States. Along the way they will be preyed upon by cartels, police, Mexican immigration authorities,

maras

and random rural gangs, robbed, enslaved, forced into narco assassin squads, and raped—an estimated eight out of ten migrant women who attempt to cross Mexico suffer sexual abuse along the way, sometimes at the hands of fellow migrants. Migrants are kidnapped en masse by Zetas, with the complicity of corrupted and terrorized local police and other authorities and of treacherous coyotes, so that their families back home or awaiting them in the US can be extorted; meanwhile the captives are tortured, raped and sometimes massacred. Thousands upon thousands of migrants have been murdered in Mexico, and many others die by falling from “La Bestia”; as many

as seventy thousand, some experts estimate, lie buried along the “death corridor” of the migrants’ trail. If the travelers do reach the northern border and actually manage to cross into the United States, they most likely will be captured by the US Border Patrol, and be deported or jailed.