The Beast (2 page)

Authors: Oscar Martinez

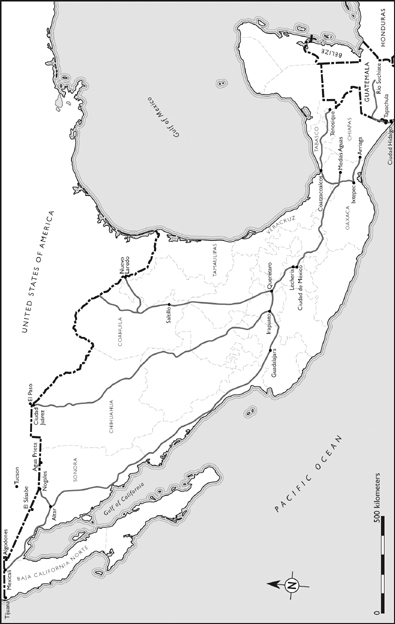

Martínez journeys north with the three brothers, Auner, El Chele and Pitbull, on a bus from Ixcuintepec to Oaxaca via a mountain road where there are few Migration Authority checkpoints, because it is so winding and treacherous. How finely and intimately Martínez captures the quiet tension of that ride, the young men’s nerves, their quality of strangers-in-a-strange-land:

El Chele and Auner are sleeping in successive rows behind him. They decided to spread themselves out, in case a cop came looking for undocumented migrants. But they still stick out enough to almost glow: three young men with loose pants and tennis shoes on a bus entirely full of indigenous folks. And they’re not just migrating, remember, they’re fleeing. You can tell. They’re the ones with the light sleep. The ones who peek out the windows when the bus comes to a stop. It doesn’t matter if the bus stops for someone to pee, or to pick up passengers, the boys get nervous every time.

In Oaxaca, they part ways; the brothers travel on, first by bus. They keep in touch, texting by cell phone. Martínez names seven other young migrants he’s met who, during those months of August and September, are killed on the journey. And then comes a final text: “

On the move. About to board the train

.” After that the communication goes dead, the brothers no longer answer messages. Martínez learns that there has been a mass kidnapping in Reynosa, thirty-five migrants seized from the train.

“

Where are you? How are you?

Nothing. No response.” End of chapter.

La Arrocera is what the migrants call the 262-kilometer route through southern Chiapas, from Tapachula to Arriaga, where they climb onto the trains. They avoid the highways and roads

because of checkpoints variously manned by the Migration Authority, police and army—“In Chiapas most denunciations filed by migrants are against the police,” writes Martínez—and instead hike through mountains, jungles and ranchlands. Migrants consider the route “lawless territory,” the most dangerous of the entire trek across Mexico, and it is called La Arrocera only because in a small settlement along the way, there is an abandoned rice warehouse. “En route to El Norte I saw, and began to understand, that the bodies left here are innumerable, and that rape is only one of the countless threats a migrant confronts.” Along the paths there are skeletons, the machete-split skulls of migrants. “Bones here aren’t a metaphor for what’s past, but for what’s coming.” There are peasant ranchers who pretend to tell the migrants which path to take, instead directing them to where rural gangs—some informal, armed with machetes, others more organized, armed with high-caliber rifles—await to assault them.

Apparently this remote countryside wasn’t always populated by murderers, robbers and rapists. What happened was that when the Mexicans living there noticed the migrants crossing their lands, so vulnerable, so frightened of ever denouncing any crime committed against them for fear of being deported, so determined only to reach their destination, their predatory instincts were awakened, and they adapted to what this new situation offered.

The Beast

offers a terrifying lesson in human cruelty, cowardice, greed and depravity. Likewise, the Zetas had never before included mass kidnappings in their criminal repertoire, but when they noticed the migrants traveling through their territories they seized upon what they perceived as a new business opportunity, forcing coyotes to work for them, and police and state authorities into complicity. When one badly beaten migrant managed to escape the house in a small town where he was being held along with dozens of other migrants, and went to the police to make a report, the police returned him to the kidnappers. Martínez and his photographer travel the La Arrocera route:

We walk on, telling ourselves that if we get attacked, we get attacked. There’s nothing we can do. The suffering that migrants endure on the trail doesn’t heal quickly. Migrants don’t just die, they’re not just maimed or shot or hacked to death. The scars of their journey don’t only mark their bodies, they run deeper than that. Living in such fear leaves something inside them, a trace and a swelling that grabs hold of their thoughts and cycles through their heads over and over. It takes at least a month of travel to reach Mexico’s northern border … Few think about the trauma endured by the thousands of Central American women that have been raped here. Who takes care of them? Who works to heal their wounds?

An expert on the migrants tells Martínez:

The biggest problem isn’t in what we can see, it’s beyond that. The problem lies in a particular understanding of things, in an entire system of logic. Migrants who are women have to play a certain role in front of their attackers, in front of the coyote and even in front of their own group of migrants, and during the whole journey they’re under the pressure of assuming this role: I know it’s going to happen to me, but I can’t help but hope that it doesn’t.

There’s an expression among the women migrants: “

cuerpomátic

. The body becomes a credit card, a new platinum-edition ‘bodymatic’ which buys you a little safety, a little bit of cash and the assurance that your travel buddies won’t get killed. Your bodymatic, except for what you get charged, buys a more comfortable ride on the train.” A migrant named Saúl tells Martínez atop “La Bestia” about a scene that’s permanently branded on his mind, when an eighteen-year-old Honduran girl he was traveling with fell from the train:

“I saw her,” he remembers, “just as she was going down, with her eyes open so wide.”

And then he was able to hear one last scream, quickly stifled by the impact of her body hitting the ground. In the distance, he saw something roll.

“Like a ball with hair. Her head, I guess.”

Throughout Central America and Mexico, as in the neighborhoods populated in the United States by migrants who manage to reach it, after years of widespread and untreated, silently endured trauma, there must be entire communities that could be converted into mental health clinics, or even asylums.

The migrants are not just pushovers and victims. Martínez shows how rugged and capable they often are—these working men, stone masons, construction workers, mechanics, peasant farmers—and how bravely they often fight back, protecting their companions and their women from being forced off the train and herded into the forest. “This is the law of The Beast that Saúl knows so well. There are only three options: give up, kill, or die.”

On one of his rides atop the train, Martínez witnesses and grippingly describes a series of battles between the migrants and their attackers, who pursue them in white pick-up trucks. He notes in conclusion: “After the attack on the train, where there were more than a hundred armed assaults, at least three murders, three injuries, and three kidnappings, there was not a single mention of the incident in the press. Neither the police nor the army showed up, and nobody filed a single report.”

Out of indifference, moral mediocrity and fear, the Central American migrants’ plight has gone mostly unnoticed in Mexico and the United States. Now and then an especially large massacre, like that of seventy-three migrants in Tamaulipas in 2011, brings some media focus, but it passes all too quickly. Catholic Church leaders such as the priest Alejandro Solalinde in Oaxaca have been at the forefront of efforts to force Mexican authorities to provide better protection for migrants. Of the many silences that overlay this story, one of the most profound is that of the United States, where the tragedy of the migrants is what news editors call a “nonstory,” one to which Washington could not be more indifferent. Throughout the 1970s and 80s the United States fanned the civil wars of Central America, supporting repressive governments, devastating those countries, and helping to create cultures of violence, all in the name of defeating communism—with a promise

to nurture just, democratic societies once peace was attained. There was no nurturing, no rebuilding, and even after the wars were over, there was no peace. The United States mostly turned its back, and now it spurns the offspring who flee what it created in Central America.

Óscar Martínez travels the length of the now nearly impregnable northern border, which has become a walled war zone where the US carries out a nightly battle against the Mexican cartels that use ever more ingenious methods to deliver their drugs across it. Here the cartels consider the migrants a nuisance, forcing them to search for ever more remote and dangerous slivers of land where they might be able to pass. Here too, they face kidnappings, assaults, betrayals and rapes. In the book’s final chapter, set in Nuevo Laredo, Martínez follows a Honduran migrant named Julio César. It is nearly impossible to cross in Nuevo Laredo, where the strong currents of the Río Bravo regularly drown the desperate migrants who try to swim it. But Julio César studies the river with the meticulous patience of a frontier tracker, walking far outside the city until he discovers a remote spot where the waters are shallower and an island divides and weakens the current. He will wait several months, until April, in the dry season, when the river will be even lower, to attempt his crossing. Julio César incarnates many of the book’s lessons: patience, courage, attentiveness, getting as close to the subject of concern as one can, “the difference between knowing and not knowing.” Those are the book’s closing words. In some ways they encapsulate the methods Óscar Martínez followed in his own crossing over into the hidden and terrifying lives of the Central American migrants.

1

On the Road: Oaxaca

There are those who migrate to El Norte because of poverty. There are those who migrate to reunite with family members. And there are those, like the Alfaro brothers, who don’t migrate. They flee. Recently, close to the brothers’ home in a small Salvadoran city, bodies started hitting the streets. The bodies fell closer and closer to the brothers’ home. And then one day the brothers received the threat. The story that follows is the escape of Auner, Pitbull, and El Chele, three migrants who never wanted to come to the United States

.

“I’m running,” Auner says, his head ducked down, not meeting my eyes, “so I don’t get killed.”

The first time I asked him, though, he told me he was migrating to try his luck. He said he was only looking for a better life,

una vida mejor

, which is a common saying on the migrant trails. But here in southern Mexico, now that Auner and I are alone, with the train tracks next to us and a cigarette resting between his lips, now that we’re apart from his two younger brothers who are playing cards in the migrant shelter’s common room, he admits that the better word to describe his journey is not migration, but escape.

“And will you come back?” I ask him.

“No,” he says, still looking at the ground. “Never.”

“So you’re giving up your country?”

“Yeah.”

“You’ll never return?”

“No … Only if anything happens to my wife or daughter.”

“And then you’ll come back?”

“Just to kill them.”

“Just to kill who?”

“I don’t even know.”

Auner knows nothing of the men he runs from. Back home, he left behind a slew of unsolved murders. Now, blindly, he runs and hides. He feels he has no time to reflect. No time to stop and think what connection he and his brothers might have with those bodies on the streets.

Auner left El Salvador, along with his wife and two-year-old daughter, two months ago. Since then he’s guided his two brothers with patience and caution. At only twenty years old, he tries hard to keep his fear in check so as not to make a false step. He doesn’t want to fall into the hands of migration authorities, doesn’t want to get deported and sent back to El Salvador, which would mean starting again from scratch. Because no matter what they’re put through or how long it takes, they must escape, he says, they must get north. To El Norte. “Get pushed back a little, okay,” Auner says, “it might happen, but we’ll only use it to gain momentum.”

Without a word, Auner gets up, ending our conversation. We walk down the dusty sidewalk, back toward the migrant shelter. We’re in the small city of Ixtepec, in the state of Oaxaca, the first stepping-stone of my journey with them. At the shelter, a place made up of palm-roof huts and half-built laundry rooms, Auner huddles next to El Chele and Pitbull, his younger brothers. El Chele has a boyish face, light skin, and a head of curly hair. Pitbull has the hardened face of an ex-con and the calloused hands of a laborer. Auner is the quiet one.

A humid heat wraps around us, so thick I feel I could push it away. The brothers are talking about the next step in their escape. There’s a decision that needs to be made: stay on the train like stowaways, or take the buses through indigenous mountain towns with the hope that they can avoid checkpoints.

A journey through the mountains would take them through the thick green Oaxaca jungle, well off the migrant train trails. But

it’s a route studded with checkpoints and migration authorities, and usually only taken with the help of a guide, or coyote. Auner first heard of the trail thanks to Alejandro Solalinde, the priest who founded and runs this migrant shelter. Solalinde is a man who understands the value in giving an extra option, even one so dangerous, to those who flee.