The Book of Basketball (17 page)

Read The Book of Basketball Online

Authors: Bill Simmons

Tags: #General, #History, #Sports & Recreation, #Sports, #Basketball - Professional, #Basketball, #National Basketball Association, #Basketball - United States, #Basketball - General

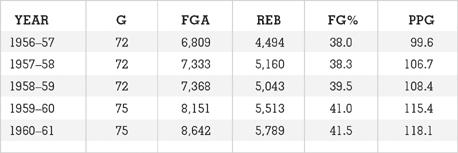

Because of the inordinately high number of possessions, the statistics from 1958 to 1962 need to be taken with an entire shaker of salt and possibly a saltwater taffy factory.

Within five seasons, scoring increased by 18.6 points, field goal attempts increased by more than 4 per quarter, there were nearly 18 more rebounds available for each team, and shooting percentages improved as teams played less and less defense.

Then the ’62 season rolled around and the following things happened:

Wilt averaged 50 points

Oscar averaged a triple double

Walt Bellamy averaged a 32–19

Russell averaged 23.6 boards and fell two behind Wilt for the rebound title

Hard to take those numbers at face value, right? And that’s before factoring in offensive goaltending (legal at the time), the lack of athletic big men (significant) and poor conditioning (which meant nobody played defense). I watched a DVD of Wilt’s 73-point game in New York and two things stood out: First, he looked like a McDonald’s All-American center playing junior high kids; nobody had the size or strength to

consider

dealing with him. Second, because of the balls-to-the-wall speed of the games, the number of touches Wilt received per quarter was almost unfathomable. Wilt averaged nearly 40 field goal attempts and another 17 free throw attempts per game during his 50-point season. Exactly forty years later, Shaq and Kobe averaged a

combined

52 points a game on nearly the same amount of combined field-goal/free-throw attempts.

18

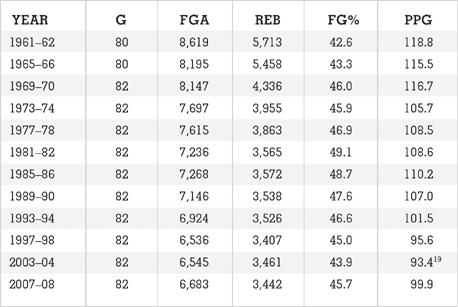

Things leveled off once teams started taking defense a little more seriously, although it took a full decade to slow down and resemble what we’re seeing now statistically (at least a little). Here’s a snapshot every four years from 1962 on. Notice how possessions, rebound totals and point totals began to

drop; how shooting percentages kept climbing; and beyond that, how the numbers jumped around from ’62 to ’74 to ’86 to ’94 to ’04 to ’08.

20

Compare the numbers from ’62 and ’08 again. Still impressed by Oscar’s triple double or Wilt slapping up a 50–25 for the season? Sure … but not as much.

1961–62: THE FIRST RIVAL

Abe Saperstein’s American Basketball League died quickly, but not before planting the seed for two future NBA ideas: a wider foul lane (16 feet) and a three-point line. The ABL also gambled on “blackballed” NBA players, including Connie Hawkins, who averaged a 28–13 for Pittsburgh and won the league’s only MVP award. In the one and only ABL Finals, the Cleveland Pipers defeated the Kansas City Steers, three games to two, with future Knicks star Dick Barnett leading the way. The ABL disbanded midway

through its second season, with the league-leading Steers declared league “champs.” Good rule of thumb: if you have a franchise named the Kansas City Steers in your professional sports league, you probably aren’t making it. If you have a team called the Hawaii Chiefs, you almost definitely aren’t making it. And if you name a team (in this case, the Pittsburgh Rens) after the abbreviation for “Renaissance,” you

definitely

aren’t making it.

21

1962–63: THE VOID

When Bob Cousy retired after getting his fifth ring, the Association lost its most popular player and someone who ranked alongside Mickey Mantle and Johnny Unitas from a cultural standpoint. Cooz got treated to an ongoing farewell tour throughout the season, as well as the first-ever super-emotional retirement ceremony that featured Cooz breaking down and some leather-lunged fan screaming, “We love ya, Cooz!” Who would step into the Cooz’s void as the league’s most beloved white guy? Did West have it in him? What about Lucas? Yup, the league was becoming blacker and blacker … and if you were a TV network thinking about buying its rights in a bigoted country, this was

not

a good thing.

(On the flip side, with Lenny Wilkens thriving on the Hawks and Oscar running the show in Cincy, the old “blacks aren’t smart enough to run a football or basketball team” stereotype started to look stupid … although it never really disappeared and even resurfaced as a key plot line during season one of

Friday Night Lights

in 2007.)

22

1963–64: THE SIT-DOWN STRIKE

January 14, 1964, Boston, Massachusetts.

(We’re going with a paragraph break and parentheses to build the dramatic tension. Sorry, I was feeling it.)

Frustrated by low wages, excessive traveling and the lack of a pension plan, the ’64 All-Stars make one of the ballsiest and shrewdest decisions in the history of professional sports, telling commissioner Walter Kennedy two hours before the All-Star Game that they won’t play without a pension agreement in place. With ABC televising the game and threatening Kennedy that a potential TV contract will disappear if the players leave them hanging in prime time, Kennedy agrees fifteen minutes before tip-off to facilitate a pension deal with the owners. Attica! Attica! Attica!

How this night never became an Emmy Award-winning documentary for HBO Sports remains one of the great mysteries in life. You had Boston battling a major blizzard that night. You had every relevant Celtic (current or retired) in the building, including the entire 1946–47 team, as well as a good chunk of the league’s retired stars playing an Old-Timers Game before the main event. You had an All-Star contest featuring five of the greatest players ever (Wilt, Russell, West, Oscar and Baylor) in their primes, as well as a number of other relevant names (Lucas, Havlicek, Heinsohn, Lenny Wilkens, Sam Jon, Hal Greer) and the greatest coach ever (Auerbach) coaching the East. You had Larry Fleisher advising the players in the locker room, a powerful lawyer who brandished significant influence with the players down the road. You had the first instance in American sports history of professional stars risking their careers and paychecks for a greater good. And ultimately, you had what turned out to be the first pension plan of the modern sports era, the first real victory for a player’s union in sports history.

23

Other than that, it was a pretty boring night.

Halberstam unearthed two classic tidbits while reporting

Breaks of the

Game.

First, the leaders of the “let’s strike” movement were Heinsohn, Russell and Wilkens. The votes were split (Halberstam’s estimation: 11–9 in favor) and a few influential stars wanted to play and negotiate later … including Wilt Chamberlain. Even during far-reaching labor disputes, Wilt did whatever was best for him. Classic. And second, just when it seemed like the dissenting players might convince everyone else to play, Lakers owner Bob Short sent a message down to the locker room ordering West and Baylor to get dressed and get their asses out on the court, sending the entire locker room into “Screw these guys, we’re not playing!” mode. And they didn’t. The seeds for free agency and big-money contracts were planted on this night. Again, you’re telling me this wouldn’t be a good HBO documentary? Where’s Liev Schreiber? Somebody pour him a coffee and drive him to a recording studio!

In general, the NBA was veering in a healthier direction. Walter Kennedy replaced Podoloff as the league’s second (and, everyone hoped, more competent) commish.

24

The Celtics became the first to routinely play five blacks at the same time as opponents emulated their aggressive style—chasing the ball defensively, keeping a center underneath to protect the rim, and using the other defenders to swarm and double-team. With the degree of difficulty rising on the offensive end, the athleticism of certain players started to flourish. You know

something

was happening since attendance rose to nearly 2.5 million and ABC forked over $4 million for a five-year rights deal despite a dearth of white stars.

The network handed its package to Roone Arledge, an innovative young executive who eventually helped revolutionize television with his work on

Monday Night Football, Wide World of Sports

, the Olympics, college football, and even

Nightline

(the first show of its kind).

25

According to Halberstam, “What ABC has to prove to a disbelieving national public, [Arledge] believed, was that this was not simply a bunch of tall awkward goons throwing a ball through a hoop, but a game of grace and power played at a fever of intensity. He was artist enough to understand and

catch the artistry of the game. He used replays endlessly to show the ballet, and to catch the intensity of the matchups … he intended to exploit as best he could the traditional rivalries, for that was one of the best things the league had going for it, genuine rivalries in which the players themselves participated. Those rivalries, Boston-Philly, New York-Baltimore, needed no ballyhoo; the athletes themselves were self-evidently proud and they liked nothing better than to beat their opponents, particularly on national television. They were, in those days, obviously motivated more by pride than money, and the cameras readily caught their pride.” For the first time, the NBA was in the right hands with a TV network.

26

1964–65: THE BIG TRADE

When the struggling Warriors sent Wilt (and his gigantic contract) back to Philly for Connie Dierking, Lee Shaffer, $150,000, Baltic Avenue, two railroads, and three immunities, the trade rejuvenated Philly and San Francisco as NBA cities—both would make the Finals within the next three years—and was covered like an actual news event. In fact, “Chamberlain Traded!” may have been the NBA’s first unorchestrated mainstream moment. Put it this way: Walter Cronkite wasn’t mentioning the NBA on the

CBS Evening News

unless it was something like “Celtics legend Bob Cousy retired today.” I’ve always called this the Mom Test. My mother was never a sports fan, so if she ever said something like, “Hey, how ’bout that Mike Tyson, can you believe he bit that guy’s ear off?” then you knew it was a huge sports moment because the people who weren’t sports fans were paying attention. Anyway, Wilt getting traded definitely passed the Mom Test. Also, I think Wilt slept with the Mom Test.

(One other biggie that year: with Tommy Heinsohn retiring after the season, Oscar Robertson replaced him as the head of the players union. I just love the fact that we live in a world where Tommy once led a labor movement.

Elgin, I gotta tell ya, I absolutely

love

your idea for a dental plan! Bing, bang, boom! That’s a Tommy Point for you, Mr. B!)

1965–66: RED’S LAST STAND

I always loved Red Auerbach for announcing his retirement

before

the ’66 season started, hoping to motivate his players and drum up national interest in an “Okay, here’s your last chance to beat me!” season. Like always, he succeeded: Boston defeated the Lakers for an eighth straight title in Red’s much-hyped farewell,

27

given an extra jolt after Game 1 of the Finals when Auerbach announced that Russell would replace him as the first black coach in professional sports history.

28

Like everything Red did, the move worked on both fronts: Boston rallied to win the

’66

title, and Russell turned out to be the perfect coach for Russell (although not right away).

Red’s retirement marked the departure of old-school coaches who didn’t need assistants, bitched out officials like they were meter maids, punched out opposing owners and hostile fans, never used clipboards to diagram plays and manned the sidelines holding only a rolled-up program. He controlled every single aspect of Boston’s franchise, coaching the team by himself, signing free agents, trading and waiving players, making draft picks, scouting college players, driving the team bus on road trips, handling the team’s business affairs and travel plans, performing illegal abortions on his players’ mistresses and everything else.

29

That’s just the way the league worked from 1946 to 1966. Red was also something of a showman, putting on foot-stomping shows when things didn’t go Boston’s way, antagonizing referees and opponents, and lighting victory cigars before games had ended. Until Wilt usurped his title, Red served as the league’s premier supervillain, the guy everyone loved to hate even as they were admitting he made the league more fun.