The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty (5 page)

Read The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty Online

Authors: Caroline Alexander

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #Naval

BOOK: The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty

10.1Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

As the various small craft tacked to and fro around the island, Edwards remained with

Pandora,

cruising offshore and making the occasional coconut run. On the afternoon of May 24, one of the midshipmen, John Sival, returned in the cutter with several striking painted canoes; but after these were examined and admired, he was sent back to complete his orders. Shortly after he left, thick weather closed in, obscuring the little craft as she bobbed dutifully back to shore, and was followed by an ugly squall that did not lift for four days. When the weather cleared on the twenty-eighth, the yawl had disappeared. Neither she nor her company of five men was ever seen again.

Pandora,

cruising offshore and making the occasional coconut run. On the afternoon of May 24, one of the midshipmen, John Sival, returned in the cutter with several striking painted canoes; but after these were examined and admired, he was sent back to complete his orders. Shortly after he left, thick weather closed in, obscuring the little craft as she bobbed dutifully back to shore, and was followed by an ugly squall that did not lift for four days. When the weather cleared on the twenty-eighth, the yawl had disappeared. Neither she nor her company of five men was ever seen again.

“It may be difficult to surmise what has been the fate of these unfortunate men,” Dr. Hamilton wrote, adding hopefully that they “had a piece of salt-beef thrown into the boat to them on leaving the ship; and it rained a good deal that night and the following day, which might satiate their thirst.”

By now, too, it was realized that the tantalizing clues of the

Bounty

’s presence were only flotsam.

Bounty

’s presence were only flotsam.

“[T]he yard and these things lay upon the beach at high water Mark & were all eaten by the Sea Worm which is a strong presumption they were drifted there by the Waves,” Edwards reported. It was concluded that they had drifted from Tubuai, where the mutineers had reported that the

Bounty

had lost most of her spars. These few odds and ends of worm-eaten wood were all that were ever found by

Pandora

of His Majesty’s Armed Vessel

Bounty.

Bounty

had lost most of her spars. These few odds and ends of worm-eaten wood were all that were ever found by

Pandora

of His Majesty’s Armed Vessel

Bounty.

The fruitless search apart, morale on board had been further lowered by the discovery, as Dr. Hamilton put it, “that the ladies of Otaheite had left us many warm tokens of their affection.” The men confined within Pandora’s Box were also far from well. Their irons chafed them badly, so much so that while they were still at Matavai Bay, Joseph Coleman’s legs had swollen alarmingly and the arms of McIntosh and Ellison had become badly “galled.” To the complaint that the irons were causing their wrists to swell, Lieutenant John Larkan had replied that “they were not intended to fit like Gloves!” Edwards had an obsessive fear that the mutineers might “taint” his crew and, under threat of severe punishment, had forbidden any communication between the parties whatsoever; but from rough memos he made, it seems he was unsuccessful. “Great difficulty created in keeping the Mutineers from conversing with the crew,” Edwards had jotted down, elsewhere noting that one of his lieutenants suspected that the prisoners had “carried on a correspondence with some of our people by Letter.”

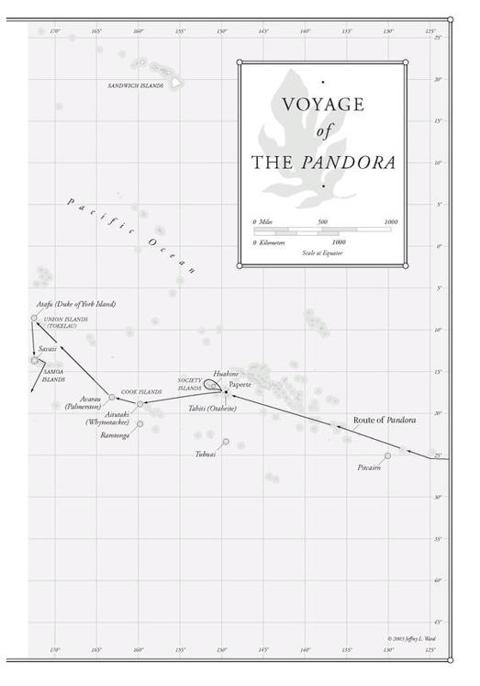

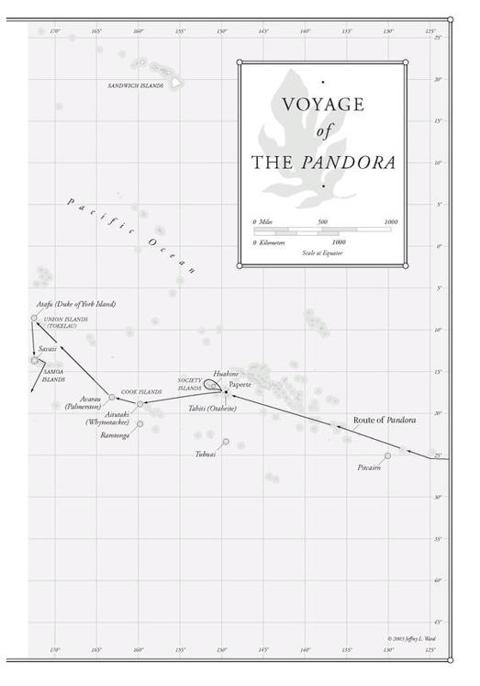

From Duke of York Island down to the rest of the Union Islands (Tokelau), thence to the Samoas, the

Pandora

continued her futile search. To aid them in making rough landfalls, Lieutenants Corner and Hayward donned cork jackets and plunged boldly into the surf ahead of the landing boats. Parakeets were purchased on one island, splendid birds resembling peacocks on another, and on others still the use of the islands’ women. Striking sights were enjoyed—the large skeleton of a whale, for example, and a deserted shrine with an altar piled with white shells. They had even discovered whole islands, whose newly bestowed names would form a satisfying addition to the report Edwards would eventually turn over to the Admiralty. In short, the

Pandora

had discovered a great deal—but nothing at all that pertained to the missing mutineers and the

Bounty.

Pandora

continued her futile search. To aid them in making rough landfalls, Lieutenants Corner and Hayward donned cork jackets and plunged boldly into the surf ahead of the landing boats. Parakeets were purchased on one island, splendid birds resembling peacocks on another, and on others still the use of the islands’ women. Striking sights were enjoyed—the large skeleton of a whale, for example, and a deserted shrine with an altar piled with white shells. They had even discovered whole islands, whose newly bestowed names would form a satisfying addition to the report Edwards would eventually turn over to the Admiralty. In short, the

Pandora

had discovered a great deal—but nothing at all that pertained to the missing mutineers and the

Bounty.

Thousands of miles from England, adrift in one of the most unknown regions of the earth, Hamilton, who seems to have enjoyed this meandering sojourn, mused tellingly on the strange peoples he had seen and their distance from civilized life: “[A]nd although that unfortunate man Christian has, in a rash unguarded moment, been tempted to swerve from his duty to his king and country, as he is in other respects of an amiable character, and respectable abilities, should he elude the hand of justice, it may be hoped he will employ his talents in humanizing the rude savages,” he wrote, in an astonishing wave of sympathy for that elusive mutineer who had, after all, consigned his captain and eighteen shipmates to what he had thought was certain death.

“[S]o that, at some future period, a British Ilion may blaze forth in the south,” Hamilton continued, working to a crescendo of sentiment, “with all the characteristic virtues of the English nation, and complete the great prophecy, by propagating the Christian knowledge amongst the infidels.” Even here, at the early stage of the

Bounty

saga, the figure of Christian himself represented a powerful, charismatic force; already there is the striking simplistic tendency to blur the mutineer’s name—Christian—with a christian cause.

Bounty

saga, the figure of Christian himself represented a powerful, charismatic force; already there is the striking simplistic tendency to blur the mutineer’s name—Christian—with a christian cause.

In the third week of June, while in the Samoas, Edwards was forced to report yet another misfortune: “[B]etween 5 & 6 o’clock of the Evening of the 22nd of June lost sight of our Tender in a thick Shower of Rain,” he noted tersely. Edwards had now lost two vessels, this one with nine men. Food and water that were meant to have been loaded onto the tender were still piled on the

Pandora

’s deck. Anamooka (Nomuka), in the Friendly Islands, was the last designated point of rendezvous in the event of a separation, and here the

Pandora

now hastened.

Pandora

’s deck. Anamooka (Nomuka), in the Friendly Islands, was the last designated point of rendezvous in the event of a separation, and here the

Pandora

now hastened.

“The people of Anamooka are the most daring set of robbers in the South Seas,” Hamilton noted matter-of-factly. Onshore, parties who disembarked to wood and water the ship were harassed as they had not been elsewhere. Edwards’s servant was stripped naked by an acquisitive crowd and forced to cover himself with his one remaining shoe. “[W]e

soon discovered the great Irishman,” Hamilton reported, “with his shoe full in one hand, and a bayonet in the other, naked and foaming mad.” While overseeing parties foraging for wood and water, Lieutenant Corner was momentarily stunned on the back of his neck by a club-wielding islander, whom the officer, recovering, shot dead in the back.

soon discovered the great Irishman,” Hamilton reported, “with his shoe full in one hand, and a bayonet in the other, naked and foaming mad.” While overseeing parties foraging for wood and water, Lieutenant Corner was momentarily stunned on the back of his neck by a club-wielding islander, whom the officer, recovering, shot dead in the back.

There was no sign of the tender.

Leaving a letter for the missing boat in the event that it turned up, Edwards pressed on to Tofua, the one island on which Bligh, Thomas Hayward and the loyalists in the open launch had briefly landed. One of Bligh’s party had been stoned to death here, and some of the men responsible for this were disconcerted to recognize Hayward.

From Tofua, the

Pandora

continued her cruising before returning to Anamooka, where there was still no word of the missing tender.

Pandora

continued her cruising before returning to Anamooka, where there was still no word of the missing tender.

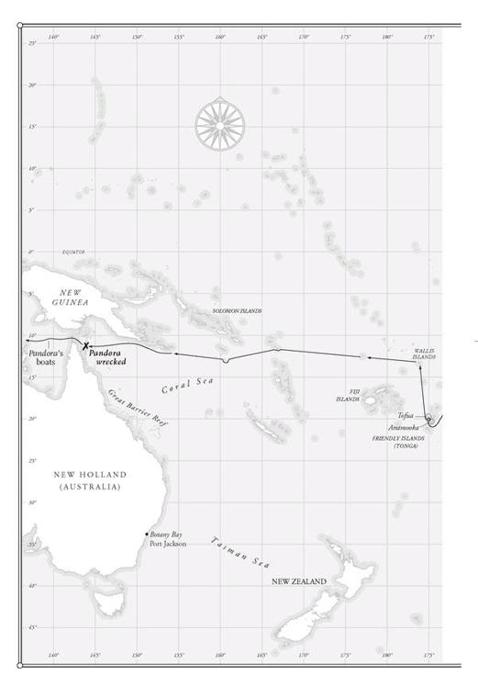

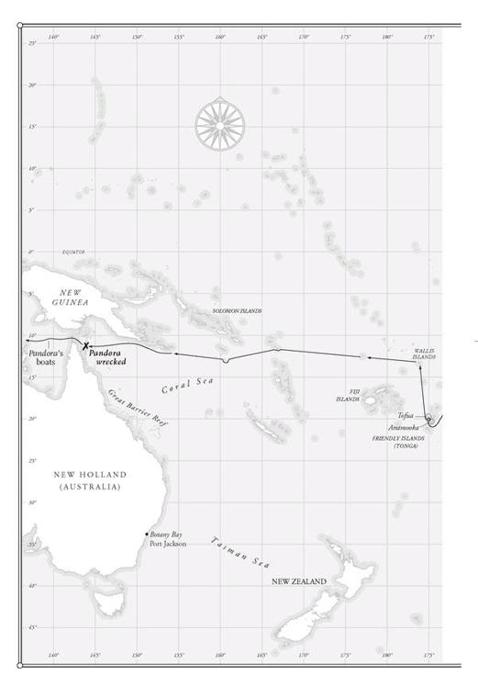

It was now early August. Edwards’s laconic report reveals nothing of his state of mind, but with two boats and fourteen men lost, uncowed mutineers on board and a recent physical attack on the most able of his crew, it is safe to hazard that he was anxious to return home. His own cabin had been broken into and books and other possessions taken as improbable prizes (James Morrison, with discernible satisfaction, had earlier reported that “a new Uniform Jacket belonging to Mr. Hayward” had been taken and, as a parting insult, donned by the thief in his canoe while in sight of the ship). Now, “thinking it time to return to England,” Edwards struck north to Wallis Island, then west for the long run to the Endeavour Strait, the route laid down by the Admiralty out of the Pacific—homeward bound.

The

Pandora

reached the Great Barrier Reef toward the end of August, and from this point on Edwards’s report is closely concerned with putting on record his persistent and conscientious depth soundings and vigilant lookout for reefs, bars and shoals. The

Pandora

was now outside the straits, the uncharted, shoal-strewn divide between Papua New Guinea and the northeastern tip of Australia. From the masthead of the

Pandora,

no route through the Barrier Reef could be seen, and Edwards turned aside to patrol its southern fringe, seeking an entrance.

Pandora

reached the Great Barrier Reef toward the end of August, and from this point on Edwards’s report is closely concerned with putting on record his persistent and conscientious depth soundings and vigilant lookout for reefs, bars and shoals. The

Pandora

was now outside the straits, the uncharted, shoal-strewn divide between Papua New Guinea and the northeastern tip of Australia. From the masthead of the

Pandora,

no route through the Barrier Reef could be seen, and Edwards turned aside to patrol its southern fringe, seeking an entrance.

After two days had been spent in this survey, a promising channel was at last spotted, and Lieutenant Corner was dispatched in the yawl to investigate. It was approaching dusk when he signaled that his reconnaissance was successful and started to return to the ship. Despite the reports of a number of eyewitnesses, it is difficult to determine exactly how subsequent events unfolded; a remark made by Dr. Hamilton suggests that Edwards may have been incautiously sailing in the dark. Previous depth soundings had failed to find bottom at 110 fathoms but now, as the ship prepared to lay to, the soundings abruptly showed 50 fathoms; and then, even before sails could be trimmed, 3 fathoms on the starboard side.

“On the evening of the 29th August the Pandora went on a Reef,” Morrison wrote bluntly, adding meaningfully, “I might say how, but it would be to no purpose”; Morrison had prefaced his report with a classical flourish,

“Vidi et Scio

”—I saw and I know. In short, despite soundings, despite advance reconnaissance, despite both his fear and his precautions, Edwards had run his ship aground.

“Vidi et Scio

”—I saw and I know. In short, despite soundings, despite advance reconnaissance, despite both his fear and his precautions, Edwards had run his ship aground.

“[T]he ship struck so violently on the Reef that the carpenters reported that she made 18 Inches of water in 5 Minutes,” the captain was compelled to write in his Admiralty report. “[I]n 5 minutes after there was 4 feet of water in the hold.” Still chained fast in the darkness of Pandora’s Box, the fourteen prisoners could only listen as sounds of imminent disaster broke around them—cries, running feet, the heavy, confused splash of a sail warped under the broken hull in an attempt to hold the leak, the ineffectual working of the pumps and more cries that spread the news that there was now nine feet of water in the hold. Coleman, McIntosh and Norman—three of the men Bligh had singled out as being innocent—were summarily released from the prison to help work the pumps, while at the same time the ship boats were readied.

In the darkness of their box, the remaining prisoners followed the sounds with growing horror; seasoned sailors, they knew the implication of each command and each failed outcome. The release of the exonerated men added to their sense that ultimate disaster was imminent, and in the strength of their terror they managed to break free of their irons. Crying through the scuttle to be released, the prisoners only drew attention to their broken bonds; and when Edwards was informed, he ordered the irons to be replaced. As the armorer left, the mutineers watched in incredulity as the scuttle was bolted shut behind him. Sentinels were placed over the box, with the instructions to shoot if there were any stirring within.

“In this miserable situation, with an expected Death before our Eyes, without the least Hope of relief & in the most trying state of suspense, we spent the Night,” Peter Heywood wrote to his mother. The water had now risen to the coamings, or hatch borders, while feet tramped overhead across the prison roof.

“I’ll be damned if they shall go without us,” someone on deck was heard to say, speaking, as it seemed to the prisoners, of the officers who were heading to the boats. The ship booms were being cut loose to make a raft, and a topmast thundered onto the deck, killing a man. High broken surf around the ship hampered all movement, and compelled the lifeboats in the black water to stay well clear.

The confusion continued until dawn, when the prisoners were able to observe through the scuttle armed officers making their way across the top of their prison to the stern ladders, where the boats now awaited. Perhaps drawn at last by the prisoners’ cries, the armorer’s mate, Joseph Hodges, suddenly appeared at the prison entrance to remove their fetters. Once down in the box, Hodges freed Muspratt and Skinner, who immediately scrambled out through the scuttle, along with Byrn who had not been in irons; in his haste to break out, Skinner left with his handcuffs still on.

Other books

The Painted Boy by DeLint, Charles

Shadow’s Lure by Jon Sprunk

Clockwork Heart by Dru Pagliassotti

Death by Silver by Melissa Scott

Found by Harlan Coben

Florida Heatwave by Michael Lister

Utopia by Ahmed Khaled Towfik

A Rake by Any Other Name by Mia Marlowe

The Voyage by Roberta Kagan

Love & Loss by C. J. Fallowfield