The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (10 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Terry spent much of his childhood happily collecting stuff: shells, rocks, fossils, and other curiosities, and over time he built some impressive collections. Our father built him a homemade rock polisher, one of many things Dad did over those years to try to connect with his geeky, brilliant son. The reading and learning that went along with the collecting actually helped to foster Terence’s interest in science and nature—and mine as well. I was never happier than on those occasions when Terence would allow me to tag along on his collecting forays. Among the best times I remember were our occasional trips to the ’dobes, an arid region near town that once had been submerged beneath an inland sea. My mother would pack a picnic lunch, and we’d head out to the badlands for a few hours of searching for shark’s teeth. The tiny, shiny, prehistoric remains were everywhere; you could sift through the soil and come up with several hundred in the course of an afternoon. We accumulated jars and jars of the darned things, learning about biology, geology, evolution, and the notion of “deep time” in the process.

Another favorite weekend outing for us was to visit the north rim of the Black Canyon National Monument, located near the town of Crawford about an hour’s drive south of Paonia. It’s one of the most spectacular geological formations on the continent. Though much smaller than the Grand Canyon, which is broad but relatively shallow, the Black Canyon is a narrow gorge slashed out of the rock over at least two million years of relentless erosion by the fast-flowing river. The gorge is one of the most extreme vertical environments I’ve ever seen, with depths that approach 3,000 ft. The Black Canyon was my first encounter with the concept of an abyss. A family story relates that when we visited the canyon on one occasion shortly after I began to talk, my mother picked me up so I could look over the railing. My comment at the time was “Big hole.” Indeed, it was.

At age eleven or twelve, Terence began collecting insects and built up a fine butterfly and moth collection, including a few exotic specimens he purchased. His tarantulas, blue morpho butterflies, and gigantic horned stag beetles arrived via the mail-order catalogs he found listed in the back of

Science News

, a thin weekly bulletin we subscribed to for years. Terence’s entomological interests proved more lasting than his other collection-related pursuits, and as a young adult he continued to seek out butterflies on his global ramblings. Though his passion was very real, he found the persona of the collector to be a good cover when traveling in tropical countries. As he noted, “When you show up in a village with a butterfly net, it’s immediately obvious to even the youngest child why you are there; and it’s non-threatening, it’s friendly. You are immediately tagged as a harmless eccentric.” Terence would know, having spent months exploring the outer islands of Indonesia under that guise in 1970, on the run from Interpol for smuggling hashish. Later, the same cover worked pretty well on our travels in Colombia when our real quest was for exotic hallucinogens.

Collecting for Terence was both a passion and a useful skill; his ability to write those tiny,

tiny

labels used in mounting specimens landed him a work-study job as an entomology technician at the California Academy of Sciences during his undergraduate years at Berkeley. Later, after returning to Berkeley from South America in 1972, he made good money mounting butterflies for a Japanese purveyor of exotic specimens. Best part about it was, he could do it totally stoned, and while holding his customary afternoon salons with the friends who dropped by his loft apartment to smoke hash and hang and rave. I fondly remember some of those sessions myself, with the late afternoon sun illuminating the dancing dust motes. That loft was the site of many a fine conversation accompanied by multiple bowls of excellent hash.

Decades later, after Terence had passed on, his lifelong interest in collecting came up in a touching and beautiful way. Many of the collections that Terence made in Indonesia and Colombia were never mounted, and remained stored in small triangular envelopes folded from paper squares, a common method of handling specimens in the field. The envelopes had been sealed with a few mothballs in large cracker tins and other containers, then packed in a trunk, and hence were perfectly preserved for decades while Terence was busy elsewhere.

After he died, his daughter Klea, then only nineteen, inherited them, and she turned out to be the perfect recipient. An excellent photographer with a highly refined aesthetic, Klea, the younger of Terence’s two children, eventually used her artistic skills and vision to transform the collection into a beautiful tribute to her father. She didn’t mount the specimens in the conventional way. Instead, she created a work in which each butterfly was photographed together with its envelope. Terence had snipped those little wrappers out of foreign newspapers, hotel stationery, notebook pages, or any other handy piece of paper. Once a specimen had been caught, he wrote the date and location on the envelope in his tiny, meticulous script. Klea’s display of these images amounted to a chronicle of Terence’s travels through the Indonesian archipelago and the jungles of Colombia. It also evoked a moment in cultural history. The newspaper clippings revealed fragments of articles and headlines about Kent State, Nixon, Vietnam; others were faded pieces of full-color magazine ads, hotel receipts, and Chinese newsprint. Together they formed a snapshot of a moment in time, juxtaposed and reinforced by the ephemerality of the specimens they held, still as vibrant and bright as the day they were collected.

Klea’s gallery installation in San Francisco in 2008 was entitled

The Butterfly Hunter,

and she later released the project as a limited edition artist book (see

www.kleamckenna.com

). She took care to ensure her quiet tribute wasn’t “about” Terence per se. She didn’t want to capitalize on his fame, but rather to present him in a pristine light as simply the butterfly hunter, someone who existed before she did, someone who became her father. His early passion would not be how the world came to know him. Many of those who saw the exhibition were not aware that it was about a celebrated figure. Her simple, elegant presentation was of a man who collected butterflies, and this man was her father. What else needs to be said?

Although Terence’s passion for insect collecting lasted well into adulthood, none of his boyhood hobbies could match amateur rocketry for sheer excitement. When he got interested in this incendiary pastime, at age eleven or twelve, our father was an enthusiastic partner. What is it about guys? They just like to blow things up, the more noisy, dangerous, and spectacular the better. Model rocketry, which was just then catching on, definitely called for adult supervision, and Dad devoted many a weekend to helping Terry build and launch the solid-fuel rockets that arrived as mail-order kits. These usually consisted of a reinforced cardboard tube, a wooden nose cone, balsa wood fins, five or six solid-fuel cartridges, some fuse cord, and (in the deluxe models) a paper parachute tied to a plastic monkey that was supposed to safely eject at the apogee of the flight. That part usually failed, and when it did, the monkey-naut ended up getting lost in the bush somewhere. But some of those kits performed pretty well; on a good day, when there was no wind, those rockets could rise a couple of thousand feet.

I’m pleased to report this is still an active hobby for a lot of youngsters. Even the venerable company we came to rely on for our kits, Estes Industries, is still in business, but their newer vehicles look a lot more impressive than the ones we launched. It’s nice to know that in this age when parents feel compelled to overprotect their kids and never let them do anything remotely dangerous (or fun), it’s still an option for young boys and girls to get into serious mischief through the reckless deployment of model rockets.

With our father keeping an eye on things, we were actually quite safety-conscious. We did most of our launching at the Paonia airport where he kept his plane, about four miles outside of town. The airstrip was on a narrow mesa the size and shape of a large aircraft carrier, surrounded for miles by sage and scrub, making it the perfect site. We dug a bunker in the earth of the hillside and reinforced it with scrap plywood and sheet metal we found in the airport hangers. The next step was to set up the rocket on its pad, attach some fuse cord to the fuel cartridge, and string it back to our makeshift barrier. Ensconced behind it, we’d light the long fuse with a match and recite the mandatory “ten-nine-eight” incantation down to liftoff. How many laws we violated on these outings I have no idea, and it didn’t really matter. It was rather rare for a plane to land at the airport back then, so we were never reported as a hazard to aviation.

Once you’re under the spell of high explosives and glimpse the potential for some really spectacular launches, you want them to be better, higher, faster, and more dangerous. What you want, in fact, is a liquid-fueled rocket. Liquid fuels like methanol and other even more volatile substances can propel a rocket 5,000 feet straight up in a flash. But liquid-fueled rockets are also inherently more dangerous; the “burn” is hard to control, and if there is an undetected leak or weakness in the rocket wall it can easily rupture. Liquid-fuel rockets are basically small bombs, which is why our father drew the line there, forbidding us to work with them.

Having never seen a line he didn’t want to cross, Terence decided that’s exactly what we’d do. We began a secret R&D program, pursued only on weekdays when our father was on the road. Terence somehow got plans for building a tiny liquid-fueled rocket out of a CO

2

cartridge like the kind used in pellet guns, about four inches long and less than an inch in diameter. I’ve forgotten what the actual fuel was, but it was probably methanol. We built a customized launch pad for this diabolical device using angle iron and conduit piping. The rocket sat at the base, loosely cradled between three conduits that provided flight guidance, or at least pointed the thing in the general direction of the sky.

Our invention took its only flight one balmy midsummer evening. Our mother had left for her bridge club, leaving us to our own devices for a few hours. We waited until it was sufficiently dark before we lugged the pad and the diminutive rocket to the football field cross the street. By then we were using a battery-operated gizmo that lit the rocket with a spark just under the exhaust nozzle—very cool. Once we’d mounted our vehicle on the pad, we conducted the obligatory countdown and triggered the ignition. Immediately a tremendous sonic boom reverberated across the valley! The rocket broke the sound barrier before it even cleared the pad, and disappeared faster than the eye could track, never to be seen again.

But we had more immediate concerns. We were utterly convinced that the sonic boom had shattered every window within a five-mile radius. We grabbed the launch pad and hightailed it back to the house, where we stashed the evidence in the patio storage room and hid ourselves in the bedroom, expecting the police to show up at any minute. But they never did. When our mother came home, we asked her as innocently as we could if she’d heard a loud noise earlier in the evening, which she hadn’t, and there were no shattered windows reported the next day. The boom we heard in our boyhood imagination was perhaps not as loud as it had

seemed

. Then again, maybe we were just lucky, and no one had been paying attention. After that episode, we halted our rocket experiments—that one was hard to top—and moved on to other things. We’d scared ourselves into discontinuing the secret program, never quite sure if we’d parked that damn thing in low earth orbit or not.

Chapter 8 - Flying, Fishing, and Hunting

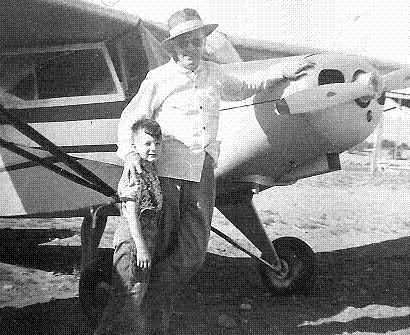

Denny and his father beside the Piper Cub, in 1956.

Our father enjoyed sharing his passion for flying with us, but by the time he got his own plane, Terence had reached early adolescence, and the tensions between them were well advanced. Whereas I flew a lot with Dad as a teenager, Terence remained mostly outside that bond. I learned to fly and land the plane pretty well, but I never got my license. The idea of sitting in a classroom studying engine mechanics and navigation never appealed to me. What’s more, though for many years I fantasized about being a professional pilot, I had severe myopia from birth and wore thick glasses, so there was little chance I’d ever achieve that childhood dream—one of many. My visual limitations led me to put a pilot’s life on the shelf, and there it stayed.

Flying was ecstasy for our father, and we shared that feeling when we flew together. Dad never felt freer or more alive than in the air, high above the cares and tribulations of the world. When I was starting to experiment with psychedelics as a teenager, I tried to explain my interest in altered states by comparing it to flying; it was a thrill, it was a rush, it was ecstasy! He couldn’t really see it. To him, everything about “drugs” was bad, and it was impossible to have a rational conversation about the topic. In that, he was like many in his generation; their drugs of choice, alcohol and tobacco, were so accepted as not to be considered drugs. My father once told me that the effects of alcohol were due to its effect on the muscles! The idea that it affected the brain was an alien concept to him. As for all the other substances that

were

referred to then (and now) as drugs in a catchall sense, he clearly knew those did affect the brain, and that had to be a bad thing.