The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (9 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

One lifelong characteristic that my rocking did reveal was a fondness for novel experience and stimulation. From an early age I was a junkie for proprioceptive novelty; I loved the feelings of floating and flying, of centrifugal acceleration and g-forces, of distorted body image and queasy stomach butterflies. The carnival rides, especially the Octopus and the Tubs Of Fun, delivered these sensations more reliably and intensely than I could induce in my chair, or on the swing set in the park, or in the occasional weightless episodes that Dad liked to indulge in when he took me up for a spin in his Piper Tri-Pacer. These were all cool and fun, but nothing delivered like the carnival rides! The rides were the ultimate cheap thrill (actually not so cheap to an eight-year-old, but I had saved my allowance).

Looking back, I have to believe that much of my later interest in drugs originated from my early love for “funny feelings” accessed through the carnival and other DIY methods of altering consciousness. In his book

The Natural Mind

, Andrew Weil writes that it is almost universal for children of a certain age to spin themselves into a falling-down state of dizziness (I tried that, too) because they enjoy the unfamiliar feeling engendered by the disorientation and loss of balance. Indeed, Weil argues that the human brain and nervous system are hardwired to seek out novel perceptions, distorted body images, visionary episodes, and other forms of ecstatic experience, and this inbuilt proclivity explains much of our fondness for substances that can trigger these altered states. Much of this activity is motivated by a curiosity akin to a scientist’s; the individual is posting data points in the unmapped territory of possible sensation. Some people go in for extreme sports like bungee jumping or skydiving for similar reasons; others pursue novel sensations through drugs, and, of course, there are those who enjoy combining pharmacologically induced alterations with their favorite risky sports, though not me. In fact, when it came to really risky behaviors like downhill skiing, rock climbing, or auto racing, I’m a bit of a wimp. I was overcautious about engaging in behaviors that were likely to get my bones broken or my ass killed, and this may be one reason I eventually came to favor drug-induced novelty over extreme sports.

This cautious streak probably stood me in good stead when it came to drugs, because as a rule I paid attention to those key variables of “set and setting” that Leary and the rest were always harping about. It made sense that one should explore altered states in a relatively safe environment. Not all my friends approached pharmacology with such common sense, and some lived to regret it; others never had that luxury, because they didn’t live. I dare say I learned a thing or two from the wondrous contraptions that showed up each summer with Happy Day Rides. My carnival experiences were formative for me, and gave me an early fondness for funny feelings that has persisted through out my life.

Chapter 6 - The Nobody People

The campaign of brotherly terror that Terence waged on me from age four or five continued for many years. It was during the nights, of course, that it reached its zenith. We shared a bedroom and had separate beds. According to Terence, he would sometimes quietly slip out of his bed, tiptoe across to mine, and stand above my sleeping form, hands raised in the tickle-attack mode, ready to pounce. And in this position he’d stand for hours, savoring the psychological meltdown he’d trigger if he acted. But he never did. It was satisfying enough just knowing that he could. Looking back, I doubt he really did this. I think his story was just another way to maintain the climate of fear.

A major element in that were the frightening stories he used to whisper as we cowered under the covers, long after lights-out. A scary TV show, a ghost story, or just some confabulation from his fertile and twisted mind, would serve as fodder for these nightly horrors. Once we watched a TV adaptation of H.H. Munro’s short story “Sredni Vashtar” presumably from a 1961 series,

Great Ghost Tales

, which first aired when I was ten. It’s a nasty little horror story about a young boy who keeps a polecat-ferret in a shed and worships the animal as a vicious, vengeful god, a secret he keeps at first from his overbearing guardian, to her ultimate misfortune. For months, Terry was able to strike the most abject fear into me by simply uttering the story’s title.

But by far the most terrifying theme of Terry’s nocturnal campaign, revisited night after night, was the Nobody People, aka the No-Body People. In the language of nineteenth-century ghost stories, the entities would be known as wraiths. Terence gave them a name and turned them loose in my already overactive and hyper-suggestible imagination. The Nobody People lived in shadows; in fact, they

were

shadows, or they existed on some gloomy threshold between the insubstantial and the real. You could see them, or sense them, at night, lurking in the shadows of the closet, or under the bed, or in the hollow of the bathtub. Rarely, you could sense them during the day, in the corners of dimly lit rooms, in basements or cellars, in the crawl spaces under the house. But primarily they were creatures of the dark and the night. You were not likely to run into a Nobody Person outside on a bright, sunny day. No, they were denizens of a shadow world; they liked to hang out in graveyards (especially in open graves), and gloomy glens, and caves.

Not that I was into hanging around such places, not on your life! I didn’t have to; the Nobody People were especially fond of the shadowy parts of our bedroom. It was Nobody People Central, our bedroom. You knew they were there, Terry said, because sometimes you’d walk into the dark room and something would flit by, maybe brush you gently in passing, and then melt into the shadows again. I bought it; I agreed that this could happen, and had happened, though of course it never did. For one thing, due to my constant, fully deployed Nobody People antennae, the idea that I would ever, under any circumstances, for any reason, walk into a darkened room without turning the light on was simply preposterous. I would be sure to snake my hand around the doorjamb and hit the light switch

before

entering a room. Terry knew of this practice and threatened to be hiding on the other side of the threshold one day where he could seize my hand and scare the living bejeezus out of me. But he never did. I guess he was too busy carrying out the rest of his terrorist agenda and just never got around to this one.

As far as I remember, the Nobody People never actually did anything bad, or did very much at all. I guess they were frightening because of the idea that we are at all times surrounded by unseen, barely sensed entities living among us, conducting their dreary affairs in a shadowy parallel world (though the term “living” is probably a misnomer, because they were understood to be, possibly, the remnants of the dead, or at least not living in the sense that

we

were living). They would have had very little power to frighten me if I had not been a willing participant-observer. I believed in them just enough that I could convince myself, in that delicate twilight between waking and actual sleep, that I could see them materializing out of the shadows, stately processions of them wafting across the room, and merging with the shadows on the other side. It’s a testament to the power of suggestion. Plant the seed of an idea in someone’s mind, repeat it often enough, and pretty soon they begin to believe it even though, rationally, it makes no sense. It also helps if the victim’s reasoning faculties and cognitive categories are still rather fluid and not yet fully formed, which was likely when I was between five and eight, the period when the Nobody People were most active.

Which moves me to ponder another aspect of this. Why do people like to be frightened? You have only to look at a list of recent blockbusters or scan the late-night TV schedule for proof that people love having the daylights scared out of them! It’s a multibillion-dollar industry. And it wouldn’t work without a voluntary and deliberate suspension of disbelief, to some extent. One has to agree to buy into the premise. Certainly I pretended not to enjoy Terence’s psychological tortures, but I suspect a part of me did enjoy them. I was titillated; there was a kind of thrill in being frightened, and it was not entirely unpleasant. To titillate now means to stimulate or excite, especially in a sexual way, but its archaic meaning was to touch lightly, or tickle. Ah hah! As I’ve noted, Terence refined the practice of tickling me into a dark art; and though I hated it, I was ambivalent. Sometimes I almost liked being tickled mercilessly, just as I sometimes liked being frightened to death.

The Nobody People were my first encounters with the idea that one can coexist with an unseen world of spirits or other entities. Certainly this perspective is integral to the shamanic worldview, and is encountered in altered states triggered by the Amazonian brew known as ayahuasca, among other shamanic substances. The ayahuasca landscape is a virtual battleground populated with malevolent spirits, but also with allies, plant teachers, animal spirit guides, ancestral spirits, and other morally ambiguous entities. The shaman’s task is essentially one of extra-dimensional diplomacy, that is, to identify and forge alliances with the beneficial entities while guarding against those that don’t necessarily have one’s best interests in mind. When I eventually accessed such realms with ayahuasca, the idea of a morally ambiguous dimension in which one rubbed up against ghostly entities (sometimes literally) was already familiar. I had been introduced to it long before by the Nobody People.

One can access those dimensions through pharmacological triggers other than ayahuasca. In fact, the nightshades, which include belladonna, the genus

Datura

, and the South American “tree daturas” are even more reliable. A full dose of datura will put you right into that twilight world where wraiths and ghosts lurk, where you can see and talk to them (though they rarely respond). I believe that accidental or deliberate encounters with the shadowy datura spaces are the basis for the belief, in many cultures, in a land of the dead or of ghosts. When encountered, these dimensions and entities certainly

seem

real enough, at least as real as ordinary waking consciousness. With practice, you can work magic in these realms that can have real impact in the ordinary reality of waking consciousness. Certainly, if you can contrive to get some of the substance into your intended victim, they can be manipulated or influenced in ways they might otherwise resist, because datura induces confusion and delirium; it undermines a person’s will, and conveniently enough, wipes out memories of what has happened. Datura, nightshade consciousness, is the ultimate power trip; it is the basis of witchcraft in European traditions and of

brujeria,

or black magic, in South America. It is not to be trifled with.

Chapter 7 - The Collector

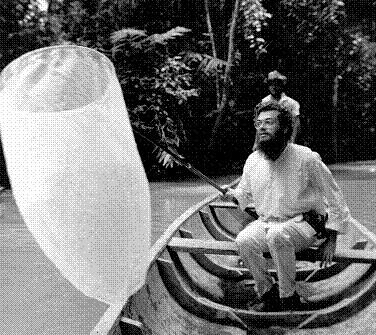

Terence in the Amazon, 1971. (Photo by S. Hartley)

According to some relatives, Terence’s early mischief was not confined to the family. He had a reputation for being hard on his peers, and some parents devised strategies to protect their offspring from his excesses. I suspect, however, that many of those kids experienced a certain thrill when Terence’s attention swung their way, unnerving though it could be. From an early age, he was front and center, the producer, director, and star of his own movie; everyone else was supporting cast. A lot of people wanted to be in his movie; a lot of people still do. And when I was a child, nobody wanted in more than I did.

Viewing their eldest child as the “smart one,” our parents made every effort to encourage Terence’s intellectual development, and to participate in his numerous hobbies. It took them about a decade to realize that I was also smart, though not in the same way. Was their reluctance to see that earlier an unconscious expression of their guilt over foisting a pesky little brother on Terry, or was it just the natural fate of a younger child? Terence was indeed a smart and curious boy, interested in many things; he also had a way of sucking the air out of a situation that could leave me gasping. Perhaps the firstborn is destined to get all the attention, the new clothes, the privileges, while a younger sib has to make do. Anyway, that’s how it seemed in our family. In many of our shared activities, Terence led and I followed, at least when he allowed it, and I didn’t really mind that. The four-year age difference made whatever Terence was into that much cooler than my own pursuits, so I obviously wanted to tag along and get involved.

Collecting was a big thing for him, as it was for many other kids back then who aspired to be scientists of a sort. The scientific interest in collections—of rocks, plants, animals, insects—now seems like a quaint relic of the Victorian era. But the life sciences have been impoverished by the decline in collecting. Today, it’s possible to get so deeply immersed in genetics and molecular biology that one never fully appreciates biodiversity from the organismic level. A student can now get a degree in biology without ever having taken a course in ecology or organismic biology, which is really a shame. Something essential is lost when you only look at biology through the lens of molecular biology.