The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (5 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

I remember Mayme as a worrier, prone to fret over the littlest things. Snakes terrified her, as did thunderstorms. She’d read somewhere that she’d be safe in a car from lightning because cars were grounded. Accordingly, Mayme would get in her car and wait out storms in the garage. Her daughter Judy’s husband, Laddie, once joked that you could go into her refrigerator on any given day and reach for the half-and-half without looking because it had been in exactly the same place for thirty years.

When I was a kid, the twins were a trip, of course. Born in 1941, they were teenagers by the mid-fifties, the early era of rock and roll—Buddy Holly, James Dean, Elvis. That was the strange, surrealistic decade when the country, still benumbed by the trauma of the war, was yearning to rediscover some semblance of normalcy, either unaware or in denial of the forces that were gathering beneath the surface, ready to burst into what American culture became in the sixties. But for the moment it was an innocent, if less than fully conscious, time.

It must be exceedingly odd to be an “identical” twin, in that no one is really identical even if they have exactly the same genes. In the fifties, that fate had to be even more difficult, because society at the time placed such emphasis on conformity, on fitting in.

That left Judy and Jody not only genetically identical, but faced with the expectation that they

should

be as identical as possible. They wore the same clothes, listened to the same music, dated the same boys—until finally Judy broke the pattern and fell in with Laddie, a James Dean type and perhaps Paonia’s first existentialist. He looked and dressed the part of a juvenile delinquent: flattop hairstyle, low-cut jeans, leather jacket, and large-buckled belt. It was all just an act. In reality he was something far more dangerous: a brooding, bookish intellectual, fond of reading Nietzsche and Heidegger, who kept such interests well concealed lest he reveal his true identity to his less brainy peers. Eventually Judy and Laddie married, and Laddie became the superintendent of schools in Delta County. He had radical ideas about education, which is to say, he sought to change a local system that in the past had stifled curiosity and the desire to learn. His reforms led to a remarkable crop of well-educated students who actually knew how to think. Unfortunately, all that happened in the eighties and nineties, long after Terence and I had a chance to benefit from the changes. But Laddie was a big influence on us in subtler ways. He was one of the few people in our youth who could actually hold his own with Terence, and in fact could beat him in most arguments. I think Terence was a little afraid of him, because he knew Laddie saw right through him. He remains one of the smartest and most perceptive people I’ve ever known.

Our mother’s youngest sister, Tress, was destined to affect our lives as well. Like Mayme, she started at Paonia High a year early; the fact that one of her half-sisters was married to the town’s venerated football coach may have helped her pull some strings. After she graduated in 1938, Tress did not attend business college like her sisters; instead she moved to Delta and spent the summer with Hadie and Joe, my parents. She had earned a scholarship at the University of Colorado, if I recall, but couldn’t afford the other expenses. That fall she moved to Glendale, California and enrolled in junior college while living with her half-brother John—the oldest son of her father’s first family—and John’s wife. After the school year ended in 1939, she and a classmate, Ray Somers, eloped to Tijuana, where the going price for a wedding ring at the time was ten cents. Tress and Ray had a “proper” ceremony later that year (and remained married until Ray’s death in 1982). They briefly returned to Paonia, where their son, Grant, was born in 1940, followed by their daughter Carolyn in 1944. Kathi, born in June 1947, was the closest in age to Terence.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Somers moved back to Glendale, and Ray got a job building Liberty Ships—a profession apparently open to young men as the war effort mounted. I mentioned how our father found such work in the Bay Area, as did one of his brothers. Ray’s stint in the Los Angeles shipyards lasted until 1944, when he reported to Fort Ord near Monterey for basic training. He figured he’d soon be on his way to Japan, but the war ended before then. In 1946, he landed his first teaching job, in Glendale, at a salary of $2,400 a year. Tress also got her teaching certificate, and the family moved north to Mountain View, California, where they both taught school until they retired in the late sixties. Terence lived for a time with the Somers during his teens, with rather unhappy results—an episode I’ll revisit later.

Despite her West Coast life, Tress’s ties to Colorado remained strong. In 1952, the couple bought a spread in the Crystal River Valley, just across McClure Pass from Paonia, and operated it as a dude ranch during the summers. They continued teaching in California in the offseason, except for a winter in the mid-fifties when they stayed at the ranch so the kids could experience a cold and snowy Colorado winter with no electricity and only a wood stove for heat.

Chair Mountain Ranch—“the ranch” to us—figured large in our childhood. Dad was an avid fisherman, and the Crystal River was known for its excellent trout fishing. Mom and Tress were close, so we ended up spending almost every summer weekend at the ranch. Mom, Terry, and I would leave on Thursday night or early Friday morning, braving the treacherous ride over McClure Pass in our Chevy coupe. It was a scary drive back then, switchbacks and gravel all the way, except when the road turned to mud in the rain. Dad would come off his weekly travels on Fridays and meet us there, and we’d have the most idyllic weekends. Dad got his fishing in, and we’d hang out with our three cousins. During the dude-ranch years, there were horses to ride by day and campfires at night, complete with roasted marshmallows, stories, and games of charades.

Our cousin Grant was good on a guitar and seemed to know all the old folk songs. I was especially fond of “Wreck on the Highway,” a tune made popular by the country star Roy Acuff in the early forties. “There was whiskey and blood all together,” one verse began, “mixed with glass they lay; death played her hand in destruction, but I didn’t hear nobody pray.” The images were just grisly and graphic enough to appeal to me as a seven-year-old. But as a good Catholic boy at the time, I wasn’t deaf to its stark warning about what happened to those who drank too much, drove too fast, and didn’t pray. Although not usually characterized as such, that song was the first I’d ever heard about the dangers of drug abuse—in this case alcohol—and I took it to heart. A decade later, I had a similar reaction to the lyrics of “Heroin,” the famous song by Velvet Underground. I have never tried heroin in my life, and have never wanted to. Hearing that song as a teenager probably helped me avoid getting tied up with one of the more harmful and dangerous recreational drugs. On the other hand, I got very involved with the psychedelics and cannabis, perhaps encouraged by the seductive lyrics of songs like “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “White Rabbit,” and so on. The moralists have leveled much criticism at rock lyrics that extol drugs, and I suppose they have a point. But for me, “Heroin,” at least, was a distinct disincentive and probably prevented me from going down a path that is better left untraveled.

Not all the songs my cousin Grant played were so grim, of course, and those summer nights beside the fire, like so many other moments at Chair Mountain Ranch, are boyhood memories I cherish.

Chapter 3 - Roots and Wars

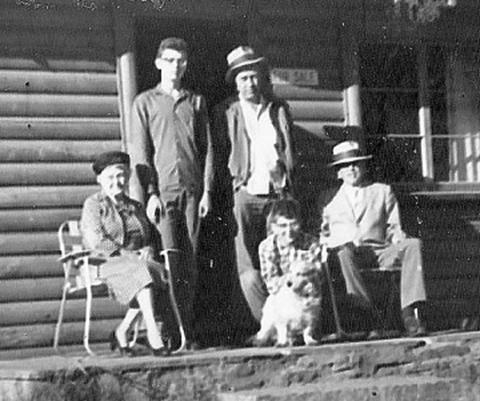

Left to right: grandmother Molly McKenna, Terence, father Joe McKenna, Dennis with Skelly, and grandfather Joseph McKenna.

Writing about our father’s family is problematic, partly because I know so little about them. Writing about our father himself is even harder, given that he was always a bit of a cipher, and remains so to this day. More to the point, it’s hard to discuss a person who had so much influence on us, and yet with whom we were so frequently in conflict. In a fragmentary memoir, his younger brother Austin remembers Dad as an Irish storyteller who saw the humor in everything and could confabulate with the best of them. His wild accounts were usually well worn, if never told the same way twice. Mom would often call him out: “Oh, Joe,” she’d say, “you’re exaggerating; it didn’t happen like that at all.” And he’d look hurt and pretend to protest, but with a twinkle in his eye. He was bullshitting, and he knew it, and he knew

you

knew it, but the tale was so good it didn’t matter. Terence inherited his father’s talent, or flaw, for never letting facts get in the way of a good story. That partly explains why, in looking back, I haven’t always been sure where the yarn spinning ends and the family history begins.

I do know my father was born high—almost two miles high, in Leadville, Colorado, on September 23, 1915. He had an older sister, Amelia, and two younger brothers: Ed, and Austin, the youngest, now nearing ninety and the only sibling still alive. Their parents, Joseph and Mary, who went by Molly, were both Irish Catholics. Over the years, both my Uncle Austin and Aunt Amelia described their family as tight-knit and affectionate; they clearly treasured their childhood memories and praised their parents for filling their household with a sense of security and love. I have the impression my paternal grandparents had permissive ideas about childrearing compared to the norms of their day.

When my father was eight or nine, the family moved sixty miles south, and a few thousand feet downhill, to Salida. My grandfather worked in a Crews-Beggs department store, one of several such branches in southern Colorado at the time. His brother, Patrick, also lived in Salida with his wife. Their sister, Mary, moved to Aspen and raised three children. Having met her once when I was very young, I remember little except my amazement that a person could be so old.

My great-grandfather was one John McKenna, a miner, who may also have used the surname McKinney or McKenney at times. He apparently married a woman who ran a boardinghouse; they definitely had a son—Joseph, my grandfather. The couple eventually separated, and John returned to Ireland, where rumor had it he remarried. His former partner, her name now lost, remarried as well; she then may have been widowed and married again. The actual kinship ties between my grandfather and his siblings, known and unknown, are thus unclear.

According to one account, our great-grandfather had a brother, Patrick, who was one of the first prospectors in Leadville and Aspen back when the silver boom began in 1879. The two McKennas supposedly filed claims for sites around Aspen, according to my Uncle Austin, who had seen documents to that effect; but whatever they made was “lost to drink and poker,” or so their ancient sister once recalled. Dad used to say that his great-uncle had once been offered the central city blocks of Aspen in exchange for a map to his grubstake mine on the flanks of Aspen Mountain. It’s nice to think the family came “that close” to owning a chunk of what is now some of the most valuable real estate on the planet, but then again, our father’s stories had a reputation for being notoriously inaccurate.

I’m not sure how our paternal grandparents met. Our father’s mother, Molly, was second-generation Irish; her ancestors had moved to America during Ireland’s great potato famine, around 1850. She was born in Denver, one of four siblings resulting from the marriage of Fred Hazeltine, a Pennsylvania mining engineer, and the former Sarah Quinn. At some point, Molly moved back to Pennsylvania to care for her mother’s disabled sister. There she met a second aunt, Lizzie Quinn, a Roman Catholic nun who went by the name of Sister Mary Amelia, who thought her bright young niece deserved a high school education. Thanks to her aunt, Molly found herself in Kansas living at an academy run by the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth, a Catholic order founded in 1858 by the members of a convent in Nashville.

Molly’s stay there would be the middle chapter in the family’s three-generation involvement with that organization. Our dad’s sister Amelia was named after the aunt who had done so much to help her mother. A bookish child, Amelia was considered the intellectual of the family. Eventually, she too became a nun with the Sisters of Charity. It was a natural progression. Career opportunities for brainy, ambitious women were limited then, and joining a convent that administered both schools and hospitals was a way to escape the era’s conventional expectations. Our Aunt Amelia, known as Sister Rose Carmel, took full advantage of her opportunities at the convent, and her family connections to it, and remained in the order for the rest of her life. She eventually earned the equivalent of a Ph.D. in chemistry, taught for years in Leavenworth, and later became a pastoral counselor in several of the hospitals administered by the order, in Denver, Santa Monica, California, and Helena, Montana.

Aunt Amelia and Terence had similar personalities and much in common, which is probably why they never got along (or, more precisely, why Terence never got along with

her

). Both were brilliant, headstrong, and rebellious. Amelia might have been a nun, but she was anything but meek and mild. She was a rabble-rouser and a troublemaker, questioning many tenets of dogma and accepted practices that were intended to keep nuns in their place. In later years, Amelia developed strong opinions regarding the exclusion of women from the priesthood, and was even heard to voice certain unflattering observations about the pope, much to the chagrin of her more timid colleagues. As a teacher, she was terrifying; many of her students relate stories of how they lived in fear of her wrath, but many of these same students recalled her tough love with affection and respect. She loved her students, but she brooked no bullshit and expected them to meet her high expectations.