The Case for Mars (5 page)

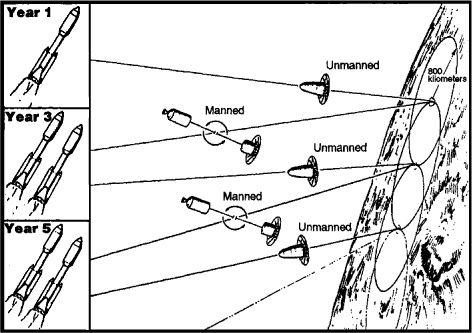

FIGURE 1.2

The Mars Direct mission sequence. The sequence begins with the launch of an unmanned Earth return vehicle (ERV) to Mars, where it will fuel itself with methane and oxygen manufactured on Mars. Thereafter, every two years, two boosters are launched. One sends an ERV to open up a new site, while the other sends a piloted hab to rendezvous with an ERV at a previously prepared site.

MAY 2018

Over time, many new exploration bases will be added, but eventually it will have to be determined which of the base regions is the best location to build an actual Mars settlement. Ideally this will be situated above a geothermally heated subsurface reservoir, which will afford the base a copious supply of hot water and electric power. Once that happens, new landings will not go to new sites. Rather, each additional hab will land at the same site. In time, a set of structures resembling a small town will slowly take form. The high cost of transportation between Earth and Mars will create a strong financial incentive to find astronauts willing to extend their surface stay beyond the basic one and a half year tour of duty. As experience is gained in living on Mars, growing food, and producing useful materials of all sorts, astronauts will extend their stay times to four years, six years, and more. As the years go by, the transportation costs to Mars will steadily decrease, driven down bw technologies and competitive bids from contractors offering to deliver cargo to support the base. Photovoltaic panels and windmills manufactured on site and new geothermal wells will add to the power supply, and locally produced inflatable plastic structures will multiply the town’s pressurized living space. As more people steadily arrive and stay longer before they leave, the population of the town will grow. In the course of things children will be born, and families raised on Mars—the first true colonists of a new branch of human civilization.

FIGURE 1.3

Linking Mars Direct habs to establish the beginnings of a Mars base. (Artwork by Carter Emmart.)

It is possible that someday millions of people will live on Mars, and call it their home. Ultimately, we can employ human technologies to alter the current frig

id, arid climate of Mars and return the planet to the warm, wet climate of its distant past. This feat, the transformation of Mars from a lifeless or near lifeless planet to a living, breathing world supporting multitudes of diverse and novel ecologies and life forms, will be one of the noblest and greatest enterprises of the human spirit. No one will be able to contemplate it and not feel prouder to be human.

That is for the future. Yet we today have a chance to pioneer the way. We can land four men and women on Mars within a decade, and begin the exploration and settlement of the Red Planet. We, and not some distant future generation, can have the eternal honor of opening this new world to humanity. All it takes is present-day technology mixed with some nineteenth-century chemical engineering, a dose of common sense, and a little bit of moxie.

FOCUS SECTION—LIVING OFF THE LAND: AMUNDSEN, FRANKLIN, AND THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

History has shown time and time again that a small group of people operating on a shoestring budget can succeed brilliantly in carrying out a program of exploration where others with vastly greater backing have repeatedly failed, provided that the small group makes intelligent use of local resources. It is a lesson that explorers of the past have ignored at their peril.

At midnight on June 16, 1903, Roald Amundsen and his crew of six sailed out under the rain-lashed skies of Christiania, Norway, bound for the Canadian Arctic and the Northwest Passage. The Passage hung before Arctic explorers as an elusive prize—nearly three centuries of effort by literally hundreds of expeditions had failed to conquer the fickle ice packs, channels, and waters of the far north.

Amundsen chased the ghost of a boyhood hero, Sir John Franklin, one of the great and ultimately tragic names of Arctic exploration. Franklin had sailed in search of the Passage nearly sixty years earlier. But whereas Amundsen sailed in a thirty-year-old sealing boat bought with money borrowed from his brother and with creditors nipping at his heels, Franklin ha

d set off with the backing of the British Admiralty. He commanded two ships, the

Erebus

and

Terror

, both displacing well over 300 tonnes, crewed by a complement of 127 men. In the words of historian Pierre Breton, the ships carried “. . . mountains of provisions and fuel and all the accouterments of nineteenth-century naval travel: fine china and cut glass, heavy Victorian silver, testaments and prayer books, copies of

Punch

, dress uniforms with brass buttons and button polishers to keep them shiny. . . .”

1

In a word, Franklin carried all tat he needed, save for what he would need to survive.

The

Erebus

and

Terror

set sail on the 19th of May, 1845, their commander expecting to discover the Northwest Passage and that feat’s attendant glory, but finding only oblivion in the end. Whalers out of Greenland spotted the Franklin expedition’s ships tethered to an iceberg on June 25. That was the last any European ever saw of the expedition. Franklin and his ships, his men, all his supplies, sailed into the Arctic wilderness and vanished.

Between 1848 and 1859 more than fifty expeditions set out to discover what befell the expedition. From what could be pieced together in the years that followed—from two brief messages left behind; from the frozen, twisted remains of some of the crew; from bits and pieces of European civilization native Eskimos picked up from the ice or looted from the ships—it became apparent that the expedition ended in disaster because, as one contemporary put it, Franklin had carried his environment to the Arctic.

Trapped in ice near King William Island in the autumn of 1846, Franklin and his men attempted to survive on their provisions of salted meat. The expedition carried meat aplenty, but none was fresh, and salt meat could not protect men from scurvy. Previous explorers had noted the anti-scurvy qualities of fresh meat, but Franklin paid no heed. He was no hunter—the expedition carried shotguns, good for partridge in the British heath perhaps, but not very useful on the Arctic ice—and chose to rely instead on rations of lemon juice. One by one the members of the expedition weakened and died, Franklin apparently on board ship in June 1847. Others, hoping to find a rescue party to the south, abandoned the ships, but literally dropped in their tracks as they dragged heavy iron and oak sledges across the Arctic wastes. All hands died.

Amundsen would follow in Franklin’s footsteps, but he would not follow him to his grave. Instead of importing his home environment, he embraced the local environment and adopted a “live off the land” strategy. He learned about the anti-scurvy qualities of caribou entrails and uncooked blubber. He learned the Eskimo way of Arctic travel, dog sled, which gave him the mobility required to hunt big game. He learned the Eskimo way of building shelters out of ice and chose the deerskin clothing of the Eskimo over the woolens that the British insisted upon.

Amundsen and his crew of six aboard the Gjöa were also frozen in, and as a result spent two winters in a small harbor on the southeast corner of King William Island, not far from where Franklin’s expedition met disaster, but they did not starve. Making good use of their dog-sled-given mobility they traveled hundreds of kilometers over land to hunt and explore, in the process not only surviving but also making the important geophysical discovery that the Earth’s magnetic poles move. The crew of the Gjöa thrived in the same environment that destroyed Franklin’s expedition. Finally breaking free of the ice in August 1905, the Gjöa set sail from King William and within weeks had forced the Northwest Passage. It took another four months of travel for Amundsen to reach an outpost where he could telegraph news of his success to his main backer in Norway, which he did, charges reversed. Six years later Amundsen would use what he had learned on King William to become the first to reach the South Pole.

2: FROM KEPLER TO THE SPACE AGE

Ships and sails proper for the heavenly air should be fashioned. Then there willand o be people, who do not shrink from the dreary vastness of space.

—Johannes Kepler to Galileo Galilei, 1609

We’ve been to Mars before. On the morning of July 20, 1976, an American spacecraft,

Viking 1

, settled down onto the Chryse Planitia—the Plains of Gold on the red planet Mars. At the moment of touchdown, though, with

Viking

resting on the surface of a planet nearly 330 million kilometers distant, no one at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, knew if the unmanned spacecraft had arrived safely or burrowed into the ground. The audience at JPL could do little more than nurse early morning cups of coffee for nearly twenty minutes before learning if

Viking

had safely landed.

Almost immediately after landing,

Viking

set to work. A preprogrammed sequence of commands instructed the lander to take a high-resolution picture of the area adjacent to one of its footpads just twenty-five seconds after landing.

Viking

relayed the picture in real time. Imaging data raced toward Earth at the speed of light as the engineers and scientists of the

Viking

program counted down the minutes to the distant radio si

gnals’ arrival. And then, with excitement, glee, and undoubtedly some astonishment they watched as, line by line, a photograph of the Martian surface slowly appeared before their eyes.

Granted, the image of a foot pad may seem a bit anticlimactic, but that first photograph delivered an immense amount of important information to the crowd at JPL. It told all that the lander had survived, and that its imaging system was working and working well. The image was clear; small rocks sharply delineated against the Martian soil, the rivets on

Viking’s

foot pad as clear as the buttons on an engineer’s conservative white shirt. After the first image, the next preprogrammed image

Viking

would capture was a scan of the horizon, a snapshot of the neighborhood. This image will probably reside forever with those who watched as the Martian surface revealed itself.

Viking

gazed out on a barren landscape littered with sharp edged rocks of all sizes. There appeared to be sand dunes in the distance, and small, undulating hills. It was an empty world, familiar, yet utterly alien.

For centuries humans had observed Mars and theorized about the planet. Their study and flights of imagination had opened enormous intellectual vistas for scholars, and revealed to all that the human mind could explore the cosmos and comprehend the complexity of the universe. Now human eyes gazed on a landscape knowing that humanity’s grasp of the universe had been extended once again, from the intellectual to the physical. It had been a long journey, one that started not in the late twentieth century, but centuries before, and one that was not without its sacrifices.

OUT OF THE DARKNESS

On the morning of Saturday, February 19, 1600, the great Italian Renaissance humanist Giordano Bruno was taken from his cell and stripped of his clothes. Naked, gagged, bound to a stake, Bruno was led through the streets of Rome, a mocking chorus of chanting Inquisitors following behind. The procession arrived at the Square of Flowers before the Theater of Pompey, the place of execution. Torch in hand, one of Bruno’s killers held a portrait of Jesus Christ in front of the condemned and demanded repentance. Bruno angrily turned his face away. The pyre was

lit, and one of the most profound minds in human history was burned alive.

Bruno was murdered for having alleged in debate in writing that the universe was infinite, that the stars were suns like our own, with other planets comprising inhabited worlds like the Earth orbiting around them. Thus, observers on those other worlds would look up and see our Sun with the Earth circling it in their sky, their heavens, and therefore, “We are in heaven.”