The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (71 page)

Read The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter Online

Authors: Kia Corthron

Tags: #race, #class, #socioeconomic, #novel, #literary, #history, #NAACP, #civil rights movement, #Maryland, #Baltimore, #Alabama, #family, #brothers, #coming of age, #growing up

Her husband's breathing was quite shallow now. She sat back in her chair gazing at him. She dozed. In her dream he held their daughter on his knee and opened her favorite book, the child seeing it through his signs and hearing it through her own voice, the story she loved to hear but that he never could.

In an old house in Paris

that was covered with vines

lived twelve little girls in two straight lines.

She had not been asleep more than two minutes. When she awoke, momentarily she forgot everything and decided this summer the three of them would go to the South Carolina beach she used to enjoy with her parents and siblings when she was growing up. Why had she never thought of that before? And then she realized Orville was gone.

Eighteen years in New York, and he had never made strong bonds outside of his wife and daughter. Who would present the eulogy?

By happenstance on the corner of 43rd and Ninth she ran into Clifford Manz, a former student of Orville's from his sign-language teaching, who expressed his sincere sorrow. Learning sign had led him to find his wife, a deaf woman. If there is anything he can do. Paulina replied instantly: Can you deliver the eulogy? You only need read it and interpret it for the deaf. The young man was naturally taken aback, but he hesitated only a moment: It would be an honor.

The day Orville had told Jade about sitting in the patch of heal-alls, which was the last time he had seen his daughter, his last conscious hour, Paulina had taken Jade to the paint store to buy the violet she had requested. Two days after Orville had passed, the evening before the funeral, Paulina was in their bedroom making final edits to the eulogy, glancing at Jade who

was asleep in her mother's bed as she had been the last six weeks since her father's admittance to the hospital. Paulina walked to the kitchen to get a glass of water and happened to pass by the can of violet paint, which she had forgotten about. It was only then that she began to cry for the first time and she didn't stop bawling until dawn.

Although Orville tended not to become close to people, he had touched a great many and they came in droves to pay their final respects. Clifford Manz stood when he was introduced to read the eulogy. He looked down at the paragraphs Paulina had written, and he spoke them with his hands, never uttering a word.

Randall stares at the cover of the journal, his eyes fixated on the word:

FICTION

. Wishing to garner from it some remnant of hope but, at last, he knows. After three long years of searching, five since B.J.'s passing, someone, perhaps their mother, had intervened, bringing Randall this gift of closure, that he may finally begin the process of mourning his brother. And, as a sob suddenly escapes, he realizes he can also now truly grieve his son. He would tell Monique, and she would be relieved, and he would move back upstairs and they would go back to being a family again. Minus one.

It occurs to him that B.J. must have died within eight months of Benja. Randall had gone to his sister's funeral, arriving just in time for the final viewing Tuesday night, staying for the service Wednesday morning, and then he was gone. It had been his first time back to Prayer Ridge since he'd left seventeen years before. Monique did not accompany him. There with his relatives he'd felt like he was sitting in a room full of strangers. He'd leaned over and kissed his sister in the casket goodbye. And now the clarity of B.J.'s passing. There was no one else left in the world who could understand the joy and the pain of growing up with the Evanses of Prayer Ridge, circa 1940.

He starts to walk out of the shop when the cashier reminds him of his change. Randall waits as the man opens the register.

“May I have a bag please?” Randall is not sure why, but suddenly he feels the need to wrap the journal in something. Protection.

The man is pulling out the sack when the phone rings. “Yeah, the latest

Rolling Stone

should be in,” absently glancing in the direction of

MUSIC

. When he hangs up, holding the change and magazine in its bag, he realizes his customer is gone.

Â

Â

1983

Â

1

May 14, 1983

Dear Uncle Dwight,

How are you?! I can't believe how long it's been!

All's well here. I just completed my finals and am looking forward to graduation next week. (Thank you again for the check!) I did well overall, 3.6 average. I know that I fluctuated for quite some time, but in the end I settled on Poli-Sci with a minor in Black Studies, a pre-law schedule. Yes, I'm following in the footsteps of my “esteemed” parents!

But I would like to live life, to learn a little about the world and myself before heading back to academia. An old dormmate of mine has been in Togo a year with the Peace Corps and has invited me to come over and visit him. Say no moreâI bought a one-way ticket! (That took care of the credit card I had just been bestowed . . .) My plan is to work and save money over the summer (and learn French!), then to fly to Lomé, stay a few weeks or months with my friend to be of use in any way I can, and then do a little traveling around the continent.

Regarding the summer job. Sadly with the recession many full-time positions have dried up. (Did you know it's been predicted by the end of the year more banks will fail than during the Depression?! Thank you, President Reagan . . .) So I feel very fortunate, having applied for internships with law firms all over the country, to have been offered three! The one that speaks to me most is Morrison & Foerster in San Francisco.

Corporate law? you may ask.

Eliot

's son??? Haha! Well, I can't see myself spending the rest of my days there, but MoFo will certainly look impressive on my résumé when it comes time to apply for law school.

This is a long way to sayâUncle Dwight, might I stay with you for the summer? I know that's

a lot

to ask! But I promise I'm neat! My internship starts June 1st so I'm flying into San Fran May 31st (TWA, arriving at SFO 2:08 PM) and the job ends August 30th so I would depart September 1st. (Flying to Africa that evening!) If this seems

huge

, then perhaps I could stay just one month? June? That would give me time to find another place for the rest of the summer, a youth hostel if nowhere else, and a first paycheck or two to offer for it.

I hope I haven't put you on the spot. I had to ask. As The Judge always says, “Nothing beats a fail but a try!”

ï

And if it's not possible,

I completely understand

. Where there's a will there's a way, and I'm sure I can drum up somewhere to crash.

But please at least consider my request, Uncle. Because the truth is I chose the San Francisco job so I would have an excuse to spend some time with my father's brother. It has been way too long!

I hope you are well, Uncle Dwightâhealthy and happy and thriving.

Love,

Your Nephew,

Rett

Dwight sits at his drafting table, absently caressing Carver on his lap, the early morning sun flooding through the east-facing picture window. He reads the neat four-page letter for the twentieth time since its arrival three days ago. Not a scratch mark, meaning Rett is either very self-assured in getting it right the first time or very meticulous in having written a first draft prior to what was sent. Dwight doesn't remember his nephew writing to him since high school, and he hasn't seen him since the boy was in the second grade. The last time he remembers even talking with him on the phone was when Rett had first started college, the fall of '79. Soon after Dwight lost control of his life again.

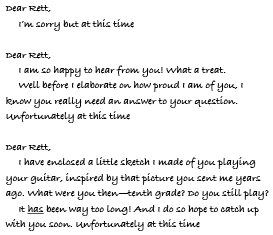

He looks at the balled-up papers in front of him.

Â

Â

He looks out the window, the bay in the distance, then stands, Carver hopping to the floor, and turns around to gaze at the loft-like space called his living room, the dining area on the other end and beyond that the kitchen, with doors along the north walls leading to the two bedrooms and bathâhis bright, spacious, quiet apartment. Keith's apartment. Dwight walks over to Keith's two paintings on the south wall, each two and a half feet wide by four. One a self-portrait, the other titled

Dwight, 1960,

both somewhere between post-modernism and abstraction. Dwight didn't think it was ego that made him feel the piece representing himself was Keith's greatest artistic triumph. By no means was it the only time he had rendered Dwight on canvas, neither could Dwight say the composition brought him any joy, but Keith, for the only time Dwight could remember, had clearly worked without the burden of self-conscious adherence to some convention or to some approved

un

convention, had instead simply followed his instincts and depicted with astonishing precision the rage and torment Dwight was undergoing at the time. Because he so recognized himself in the work, upon its completion a year after the date in the title Dwight had snarled to its artist that it belonged in the garbage. Given the unrestrained shouting match that ensued, he assumed Keith had followed his instructions to the letter, and for good measure had also tossed any other likenesses of Dwight Campbell he had been fool enough to waste his time on. So Dwight had wept when he found the piece in Keith's collection posthumously. He'd hung it as a reminder of what he was and never hoped to be again, and as a tribute to his closest friend.

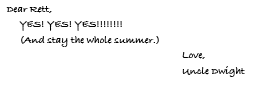

Dwight sits at the drawing board again. After a few moments he carefully reaches for his pen.

Â

Â

He studies the note one last time, bites his lower lip, and seals the envelope.

He dishes out a wet canned breakfast and pours fresh water for tan Carver and her black brother Banneker, cleans the litter box, and by quarter to seven leaves his apartment to walk the three blocks to the school. He is fifty-four and slim, wearing one of his three identical gray jumpsuit uniforms. On the way he passes the mailbox. He pulls down the trap, and sees a little woman hanging inside. It's Tiny, Uncle Sam's mother, the one the whites lynched. She's freshly dead, the noose around her neck, head tilted lazily to the side. Then she comes back to life, lifting her face to look at Dwight. “Sure you wanna do this?” He drops the letter in and shuts the door with her still hanging, then heads off to work.

He's always the first to arrive, last to leave. After he climbs to the third and top floor where his small office/broom closet is tucked away and sets down his jacket and shoulder bag, he rolls out his cleaning cart and takes the freight elevator down to the first floor. He vacuums the administrative offices, emptying the wastebaskets. Then he moves on to the bathrooms: filling the soap dispensers, replenishing the toilet paper, and on the second floor where the older girls are he empties the sanitary napkin receptacles. He finishes around eight, then goes outside to gather any after-school playground litterâa pink sweater and plastic ball for Lost and Found. He notices a screw loose on the swing set and tightens it. Between 8:15 and 8:30 the teachers materialize, most of them waving and smiling at Dwight in greeting. A few don't wave. A few are suspicious of the custodian, knowing his history, but most of the faculty consider themselves progressive, all about granting second chances.

As time moves closer to nine the children begin arriving, many of them waving with innocent exuberance, “Hi, Mr. Campbell!” Dwight smiles and waves back.

After the late bell he works alone again, oddly feeling the guilt-giddiness of a kid who's supposed to be in school but is not, some Pavlovian ingrained response. On his way back inside a little white girl comes running out to find him, trying to suppress her pride at being chosen for the important mission of conveying a directive to the janitor. “Mr. Campbell, Heather Addlewood threw up in Mrs. Eisentrout's class!”

“Okay, I'm comin.” The child runs back in, wishing to beat Dwight so she would be able to make the crucial announcement of his impending arrival before his appearance rendered her proclamation moot. Dwight had been hoping puke patrol would be over by the end of February. He prays this isn't the start of some school-wide epidemic.

He enters Mrs. Eisentrout's classroom armed with cleaners and disinfectant, the students mysteriously missing. He has no trouble locating the soiled area, the stench greeting him instantly, the third-row desk overflowing with the gunk. The teacher is writing on the board today's schedule for her fifth grade.

“Thank goodness they had music first thing and I could send them all to the auditorium. Little hard to keep their minds on long division when the room reeks of upchuck.” She shakes her head. “The nurse called her mother. Why do they send their kids to school sick?”

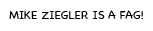

Dwight shakes his head in sympathy and in something like solidarity, except as he is alone in wiping up the revolting muck he has no real sense that he and Mrs. Eisentrout are in this together. He's finishing the task when he notices something carved into the adjacent desk. It will be his job to take a scraper and rub it out. He'll bring that tool with him when he does such chores after dismissal, but for now he shows the graffito (the word's singular form he'd learned when once given a citation for such an infraction) to Mrs. Eisentrout.

Â

Â

The teacher sighs. “I'll talk to him.”

At 10:30 Dwight goes back to his office, taking from his bag his reading glasses and a paperback,

Song of Solomon

. He sits at his well-worn wooden table, an ancient high school student desk. When this job was offered to him last summer, he was informed of the irregular hours. Some work needs to be performed before the start of the school day, other tasks post-dismissal, so the schedule was Monday through Friday 7 to 10 and noon to 5. When he asked for a slight adjustment, 7 to 10:30 and 12:30 to 5 so he could finish his hour-long 11 a.m. meeting, the principal was kindly accommodating. The Presbyterian Church is just a five-minute walk away so at 10:50 he closes his book and gets up to leave, always making sure he's a little early to allow for any unexpected delays because at eleven the room is locked and not unlocked until the meeting is over.

There are nineteen in the circle, various genders and races and sexual orientations. The space is already filled with cigarette smoke. They sit quietly, the attention of the room moving around to the left, all who wish to take a turn speaking, all who speak respecting the three-minute limit. When the person to his right begins to utter quietly, Dwight's heart starts pounding, hearing little in anticipation of his own turn.

“My name is Dwight, and I'm an addict. Some of you regulars know it would take too long for me to list all the drugs, let's just say I did em all, OD'd twice on speed, three times smack, every day I'm grateful, every day aware a the miracle I'm still here.” He is momentarily silent. “I haven't dropped acid in three or four years. But I just had a flashback. My great-aunt was lynched, that's not the drugs, that's the truth. Well she just talked to me through the mailbox.” He laughs softly. “I think this is related to the fact that my nephew is comin to stay with me for the summer. He just graduated from college, wants to go to law school like his daddy, my brother. Over the years I'd receive the occasional correspondence from him, hardly ever did I reply but he never gave up on his uncle, neverâ” He swallows. “He's got it all together. I haven't seen him since he was a little boy, haven't heard his voice in years. But that letter. You just feel it.

Confidence.

” He takes a breath. “I'm scared. I haven't been around family in a while. Been clean two years, I don't wanna go back and oh God I don't wanna go back in frontaâ” Wiping an eye.

“When he asked could he come I thought

no, no, no

. And then. He's all grown up. I say no now, might never get another chance.” Looking at the floor, he smiles. “I think my sponsor and I will remain in very close contact till September.”