The City of Dreaming Books (25 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

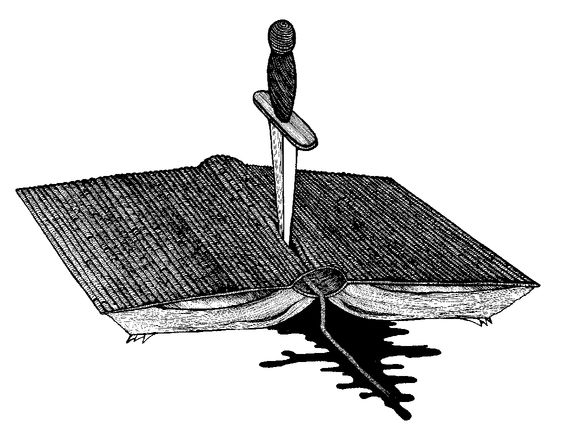

Toxicotomes impregnated with poisons transmissible by touch had been particularly popular in the Zamonian Middle Ages. They were used to remove political opponents and topple kings, but also to eliminate rival authors or persistently hostile reviewers. The wealth of imagination with which the Bookemists of the era had developed a multitude of such poisons was extremely impressive. Contact with a single page could strike you deaf and/or dumb, paralyse or drive you mad, infect you with an incurable disease or send you to your eternal rest. Many toxins induced lethal paroxysms of laughter or loss of memory, delirium or the shakes. Others caused your hair and teeth to fall out or desiccated your tongue. There was even a poison which, if you came into contact with it, filled your ears with a chorus of voices so shrill and piercing that you ended by jumping out of a window of your own accord. The book that had drugged me was innocuous by comparison.

According to Colophonius Regenschein, a certain publisher of this period had not only impregnated one copy of each of his editions with a deadly contact poison but actually advertised the fact. You would have thought that such books would languish on the shelves, but the opposite happened. They sold like hot cakes because they offered a thrill no normal book could provide: a frisson of genuine danger. They were the most exciting books on the market. People read them with hands atremble and foreheads filmed with sweat, no matter how boring their contents. Books of this kind were especially popular with retired soldiers and elderly adventurers who could not afford to expose themselves to undue physical exertion for health reasons.

Toxicotomes had gone out of fashion at the end of the Zamonian Middle Ages because their dissemination was incompatible with modern laws. What now spread fear and consternation were

Analphabetic Terrortomes

, imitations and developments of book traps smuggled into bookshops by a radical sect of bibliophobes. When someone opened an Analphabetic Terrortome the entire bookshop blew up. The sect that manufactured these bombs had no name because its members were opposed to words on principle. They also rejected sentences, paragraphs, chapters, novels, any form of prose, any form of verse and books in general. To them, commercial establishments that sold books constituted an affront to their fanatical illiteracy and were hotbeds of evil that had to be wiped off the face of Zamonia. They smuggled their treacherous explosive volumes into bookshops and libraries, concealed them among popular bestsellers and beat a retreat. It wouldn’t be long, they reckoned, before no one dared to open a book at all.

Analphabetic Terrortomes

, imitations and developments of book traps smuggled into bookshops by a radical sect of bibliophobes. When someone opened an Analphabetic Terrortome the entire bookshop blew up. The sect that manufactured these bombs had no name because its members were opposed to words on principle. They also rejected sentences, paragraphs, chapters, novels, any form of prose, any form of verse and books in general. To them, commercial establishments that sold books constituted an affront to their fanatical illiteracy and were hotbeds of evil that had to be wiped off the face of Zamonia. They smuggled their treacherous explosive volumes into bookshops and libraries, concealed them among popular bestsellers and beat a retreat. It wouldn’t be long, they reckoned, before no one dared to open a book at all.

However, they had underestimated the passion for literature common among Zamonians, who were quite prepared to risk getting their heads blown off for the sake of a good read. Explosions became rarer as time went by and the sect eventually broke up because its leader blew off his own head while constructing a bomb that detonated prematurely. For all that, opening books remained a risky business. Analphabetic Terrortomes might still be lurking anywhere, even after centuries, because vast numbers had been put into circulation. Hence the sporadic destruction of antiquarian bookshops in particular, some of which were reduced to little more than deep craters. Fifteen of them had been blown sky-high in Bookholm alone.

There were as many Hazardous Books in Zamonia as there were reasons for wishing someone ill. Among the motives that prompted their manufacture were revenge, greed, envy and resentment - and, when jealousy or unrequited love were involved, infatuation. Poisoned dog-ears with razor-sharp edges, vignettes whose touch arrested the breathing, ex-libris impregnated with olfactory poisons - nothing remained untried. Those who habitually moistened their fingertips with saliva when turning pages were more at risk than most because they might convey tiny amounts of poison from the paper to their tongues and then collapse, gasping for breath, their lips flecked with bloodstained foam. Small cuts sustained from gilt-edged pages infected with bacteria could cause blood poisoning. Encoded posthypnotic commands hidden in Bookemists’ books were capable, days later, of causing their readers to jump off a cliff into the sea or drink a pint of mercury.

As time went by, stories about the Hazardous Books proliferated to such an extent that it became almost impossible to distinguish between fact and fiction. The catacombs of Bookholm were reputed to contain books capable of self-propulsion, books that could crawl or even fly, books more ferocious and voracious than many a predator or insect - books that could only be defeated by force of arms.

It was rumoured that some books whispered and groaned in the dark while others strangled people with bookmark ribbons if they nodded off while reading them. It could even happen that a reader was devoured alive by a Hazardous Book and never seen again. All that remained was his empty armchair with the book lying open on it, his sole memorial the fact that it now featured a new protagonist who bore his name.

Such were the ideas and stories that ran through my mind as I roamed the catacombs, dear readers. Although I’m no believer in ghosts or witchcraft or Ugglian curses or hocus-pocus of any description, the existence of the Hazardous Books was something I knew from personal experience. I resolved never to touch another of the books down here.

So I simply walked on without paying them much attention. My optimism had evaporated by now. All I could see were walls lined with books I dared not touch and the occasional dead jellyfish. I might just as well have been walking through a clump of stinging nettles. Apart from my own footsteps, I heard just about every sinister noise to be found in Zamonian horror stories: rustles and bangs, whimpers and howls, whispers and giggles. It was like listening to a piece of gruesic composed by Octavius Shrooti. The noises undoubtedly emanated from the city’s sewers and were of Overworldly origin, but they had been transformed into entirely new sounds on their way through all those layers of soil and along all those tunnels and passages. I was hearing the ghostly music of the catacombs.

At some stage I sank to the ground. How long had I been walking? Half a day? A day? Two days? I was utterly disorientated, temporally, spatially and psychologically. My legs ached, my head rang like a bell. I simply lay there and listened to the unnerving sounds of the catacombs. Then I fell into an exhausted sleep.

The Sea and the Lighthouses

I

awoke unrefreshed, not only hungry and thirsty but in unwelcome company. Crawling and scrabbling around on my face and stomach were dozens of insects and other noisome creatures: transparent maggots, worms, snakes, phosphorescent beetles, long-legged Bookhoppers, ear-wigs armed with outsize pincers, eyeless white spiders. I leapt to my feet with a horrified scream and lashed out wildly. The creatures flew in all directions as I performed a grotesque dance, flailing away at my cloak in a panic. A gigantic bookworm emitted one last, vicious hiss and rattled its scales at me before disappearing behind a heap of books. It wasn’t until I was certain of having put the last of the vermin to flight that I recovered some of my composure.

awoke unrefreshed, not only hungry and thirsty but in unwelcome company. Crawling and scrabbling around on my face and stomach were dozens of insects and other noisome creatures: transparent maggots, worms, snakes, phosphorescent beetles, long-legged Bookhoppers, ear-wigs armed with outsize pincers, eyeless white spiders. I leapt to my feet with a horrified scream and lashed out wildly. The creatures flew in all directions as I performed a grotesque dance, flailing away at my cloak in a panic. A gigantic bookworm emitted one last, vicious hiss and rattled its scales at me before disappearing behind a heap of books. It wasn’t until I was certain of having put the last of the vermin to flight that I recovered some of my composure.

Then I set off again. What else could I do? By now all my confidence had left me. There was no reason to believe that I was any nearer an exit. I might even have gone deeper still, and those insects had shown how quickly one could become part of the underworld’s merciless food chain. Nor was the recurrent sight of half-dead jellyfish calculated to raise my spirits; their futile attempts to escape were all too reminiscent of my own predicament. Like them I would soon be lying dead on some tunnel floor, a desiccated, emaciated cadaver eaten away by vermin. And all because of a manuscript.

The thought of it made me call a brief halt and take it out again. Could I decipher the underlying message that had landed me in this ticklish situation and might possibly help to extricate me from it? It was a foolish, desperate idea, but the only one I could come up with at that moment. So I proceeded to study the manuscript once more. I perused it with the same enthusiasm, the same reactions I’d displayed at first reading, and it afforded me temporary relief. Then I came to the last sentence:

‘

This is where my story begins

.’

This is where my story begins

.’

It sounded so hopeful, so boundlessly optimistic, that tears of joy welled up in my eyes. No story could have got off to a more confident start. I pocketed the manuscript and set off once more, pondering on the words that had reactivated my brain. I was suddenly overcome by a feeling that the mysterious author had meant to tell me something; that, wherever he might be at this moment, he was speaking to me.

‘

This is where my story begins

.’

This is where my story begins

.’

But what was he implying? That my own story was only just beginning? That would be a very consoling thought. Or ought I to take the sentence even more literally?

Don’t ask me why I believed this, my faithful readers, but I felt sure the sentence was a riddle whose solution would help me to regain my freedom. Very well, I would take it literally.

‘

This is where my story begins.

’

This is where my story begins.

’

Where was ‘this’? Here in the catacombs? Here where I happened to be at this moment? Agreed! But whose story did the author mean, if not mine? What else was here apart from myself? Insects, of course. And, needless to say, books.

That flash of inspiration almost killed me, it hit me so hard!

Books

, you idiot! It was thoroughly idiotic of me to ignore the books. If I could expect help from any quarter, it was from them. Although surrounded by thousands of wise potential advisers, I had been deterred from enlisting their aid by one unpleasant experience and a handful of legends about the Hazardous Books.

Books

, you idiot! It was thoroughly idiotic of me to ignore the books. If I could expect help from any quarter, it was from them. Although surrounded by thousands of wise potential advisers, I had been deterred from enlisting their aid by one unpleasant experience and a handful of legends about the Hazardous Books.

I was involuntarily reminded of the way in which Colophonius Regenschein had found his bearings by means of the books around him. It was mainly the order in which the various libraries and collections in the catacombs were arranged that had led him to his discoveries. That being so, wouldn’t it be logical if the books could also guide a person back to the surface?

Although not blessed with Regenschein’s great expertise, I did have some knowledge of Zamonian literature, and it required no stroke of genius to determine a book’s age from its condition, author, contents and imprint. It was really quite simple: the older the books around me, the deeper in the catacombs I must be. The more recent they became, the closer I would be to an exit. Not invariably, of course, but often enough. Why? Because most libraries reflected the time in which their owners lived. Equipped with this simple compass, I would be able to get my bearings and find my way back to the surface and freedom -

if

I could summon up the courage to examine the books.

if

I could summon up the courage to examine the books.

What did I have to lose? If a Hazardous Book ripped off my head or drilled me between the eyes with a poisoned arrow I would at least meet a quick and merciful end instead of dying a slow, agonising death from starvation or being eaten alive by insects.

Better to die on my feet than crawling along like a jellyfish! All I had to do now was to overcome my fear and open a book. I came to a halt.

Other books

Ramage's Devil by Dudley Pope

Zein: The Homecoming by Graham J. Wood

An Ideal Husband? by Michelle Styles

Gardner, John by Licence Renewed(v2.0)[htm]

The New Neighbor by Garton, Ray

Outlaw's Baby: A Bad Boy Secret Baby Romance by Marci Fawn

Disciplining Little Abby by Serafine Laveaux

A Little Bit Wild by Victoria Dahl

House of Darkness House of Light by Andrea Perron

More Pleasures by MS Parker