The City of Dreaming Books (22 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

‘Are you prepared to enter the catacombs of Bookholm?’ Smyke asked, pointing along the tunnel with his seven left arms. ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be a guided tour. Return journey guaranteed.’

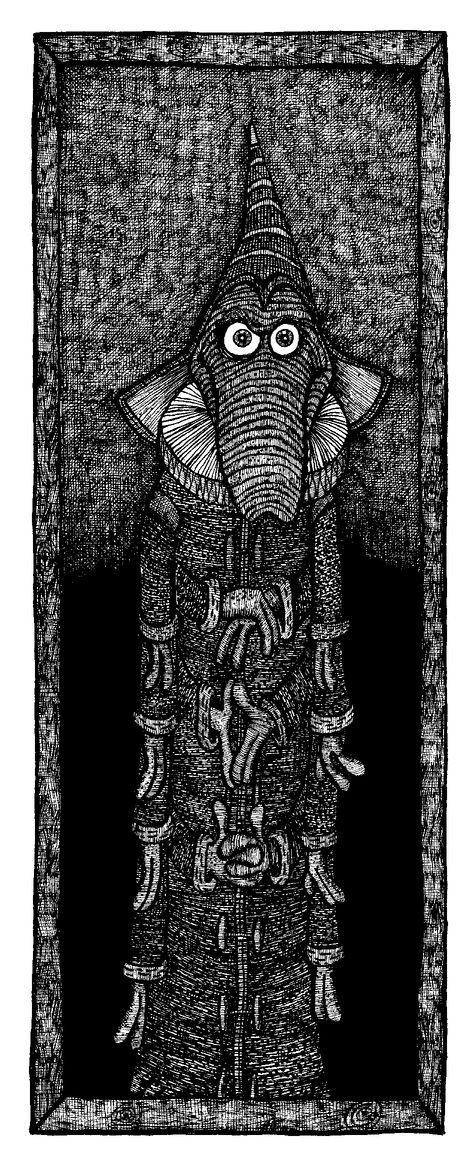

We entered the passage, which was discreetly lit by jellyfish lamps. The prevailing atmosphere resembled the one in my trombophone vision, except that here there were no shelves and no books. Hanging on the walls at long intervals were some large oil paintings, all of which depicted Shark Grubs in various costumes.

‘They’re all Smykes,’ the literary scholar said with a touch of pride as we made our way past the portraits.

‘My ancestors,’ he went on. ‘There! That’s Prosperius Smyke, formerly chief executioner of Florinth. The one with the crafty expression is Harimata Smyke, a notorious spy who died three centuries ago. The ugly fellow beyond her is Halirrhotius Smyke, a pirate who resorted to eating his own children when becalmed in the doldrums. Ah well, we can’t choose our relations, can we? The Smyke family is scattered the length and breadth of Zamonia.’

One of the portraits aroused my particular interest. The subject was exceptionally thin for his breed. He displayed none of the obesity typical of Shark Grubs and had piercing eyes in which I seemed to detect a glint of insanity.

‘Hagob Salbandian Smyke,’ said Pfistomel. ‘An immediate forebear of mine. It was he who . . . But more of that later. Hagob was an artist. He produced sculptures. My home is full of them.’

‘Really?’ I interposed. ‘I haven’t seen a single sculpture on your premises.’

‘No wonder,’ Smyke replied. ‘They’re invisible to the naked eye. Hagob made microsculptures.’

‘Microsculptures?’

‘Yes. He began with cherry stones and grains of rice, but his works steadily diminished in size. He ended by carving them out of the tip of a single hair.’

‘Is that possible?’

‘Not really, but Hagob managed it. I’ll show you some of them under a microscope when we get back. He carved the whole of the Battle of Nurn Forest on an eyelash.’

‘You come of unusual stock,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ Smyke sighed. ‘Alas!’

The further we progressed along the steeply sloping passage the older the portraits became. One could tell this from the hairline cracks in their layers of oil paints and glazes, their increasingly primitive technique and their subjects’ style of dress.

‘We Smykes can trace the roots of our family tree to the edge of the Zamonian Ocean and beyond. They even extend beneath its surface - down, deep down to the ocean floor itself. But I’m not indulging in false modesty, truly not, when I say that my ancestry means little to me. The Smykes have always kept their distance from each other. Love of solitude is another inherited family trait.’

The passage changed direction but remained as featureless as ever. We passed an occasional jellyfish lamp on the ceiling or portrait on the wall, but that was all.

‘Habibullah Smyke,’ said my companion. ‘Also called “The Desert Scorpion”. He used to drown his enemies in sand - you can do that, as long as it’s quicksand.’

He pointed to another painting.

‘Okudato “Godfather” Smyke, once the underworld boss of Ironville. He got a blacksmith to forge him a set of steel dentures and devoured his rivals alive - the only Smyke to have sunk to the level of the Demonocles. And that’s Termagenta Smyke, who skewered all her husbands with a red-hot . . . Ugh, it’s too distasteful. I’ll spare us any further details, we’re nearly there in any case.’

The passage had been descending steeply all this time, so we must have been pretty far below ground, but I still hadn’t seen a single book. Suddenly it ended and we found ourselves confronted by a dark wooden door with ironwork fittings.

‘Here we are,’ said Smyke. He bent down, put a hand to his mouth and muttered something unintelligible at the rusty old lock.

‘A Bookemistic incantatory lock,’ he explained almost apologetically when he straightened up. The door creaked open by itself.

‘An alchemistic falderal from the last century,’ Smyke went on. ‘Nothing magical about it, just a gravity-operated mechanism activated by sound waves, though they have to be the right sound waves. Saves messing around with a key. After you!’

I walked through the doorway and abruptly found myself standing in the biggest underground chamber I’d ever seen. Devoid of any shape that could have been defined in geometrical terms, it stretched away in all directions, upwards, downwards and sideways. Chasms yawned, stone ceilings soared to an immense height overhead, terraces rose in tiers, caves branched off with other caves branching off them, huge dripstones hung from above or jutted from below, the latter with spiral staircases hewn into them, stone arches spanned ravines - and everywhere jellyfish lamps dispensed their pulsating glow and candelabra were suspended on chains or let into the walls. This was a chamber composed of many chambers - one in which the eye could roam without end until all was engulfed in darkness. I had never felt so disorientated. But the truly astonishing feature of the place was not its shape, size or lighting; it was the fact that it was full of books.

‘This is my library,’ Smyke said as casually as if he had opened the door of a garden shed.

There must have been hundreds of thousands if not millions of books - more than I’d seen in the whole of Bookholm put together! Every part of the monstrous dripstone cave had been used as a repository for books. Some of the shelves had been hewn out of the living rock, others were made of timber and soared to dizzy heights with long ladders leading to them. Mountainous piles of books stood in rows like endless alpine ranges. There were plain raw deal bookcases, valuable antiquarians’ cabinets with glazed doors, baskets, tubs, handcarts and crates full of books.

‘I myself have no idea how many there are,’ said Smyke, as if he had read my thoughts, ‘- no idea whatsoever. I only know they all belong to me under the terms of the Bookholmian Constitution.’

‘Is this a genuine dripstone cave,’ I asked, ‘or was it hewn out of the rock?’

‘Most of it originated naturally, I believe. Everything here must once have been under water. That’s indicated by the fossils embedded in the rock - for which any Zamonian biologist would give his right hand.’ Smyke chuckled. ‘But all the surfaces look polished, hence the artificial impression. I surmise that some industrious souls gave nature a helping hand - more than that I can’t say.’

‘And all these books belong to you?’ I said stupidly. The idea that such an immense collection could belong to one person struck me as absurd.

‘Yes. I inherited them.’

‘You mean they’re a family heirloom? An heirloom handed down by your - forgive me for citing your own description - degenerate ancestors? They must have been remarkably cultivated and refined for all that.’

‘Oh, please don’t think that refinement and degeneracy are mutually exclusive.’ Smyke heaved a sigh. He took a book from a shelf and regarded it meditatively.

‘I should point out that none of this belonged to me at birth,’ he went on. ‘I grew up in Grailsund, a long way from Bookholm. The business I engaged in there had absolutely no connection with books. It didn’t go too well, either, so one day I found myself in dire financial straits. Don’t worry, though, I won’t bore you with the story of my youthful poverty. I’m just coming to the nice part.’

Smyke replaced the book. My eyes strayed over the incredible subterranean scenery. Some white bats were fluttering among the stalactites high overhead.

‘One day I received a letter from a Bookholm solicitor,’ Smyke continued. ‘I had very little desire to visit this musty old city of books, to be honest, but the letter informed me that I had come into an inheritance, and if I didn’t take it up in person it would pass to the municipality. Although it didn’t say what the inheritance comprised or what it was worth, I would at that time have welcomed ownership of a public convenience, so I set off for Bookholm. It transpired that my inheritance - the estate of my great-uncle Hagob Salbandian - consisted of the small house that is now some two thousand feet above our heads.’

Two thousand feet of soil and rock between us and the surface? It wasn’t a particularly pleasant thought.

‘I took up my inheritance with a touch of disappointment, of course, because I’d travelled to Bookholm filled with visions of a considerably more sensational bequest. For all that, a house of my own - a listed building on which I wouldn’t have to pay rent - was an improvement on my existing circumstances. As a citizen of Bookholm I was entitled to study at the local university. Since it was obvious how to make money in this city, I enrolled in the courses on Zamonian literature, antiquarianism and typography. I also did a wide variety of menial jobs ranging from book-walking to scissor-washing. A person with fourteen hands can always find work.’

Smyke looked down at his numerous hands and sighed.

‘One night, while combing my cellar for something worth selling, I found that its only contents were empty bookcases. Well, bookcases are always in demand in Bookholm, so I thought I’d take one upstairs, spruce it up a little and sell it. When I tried to wrench it off the wall - well, you saw what happened just now: the secret door swung open, revealing the route to Hagob Salbandian’s real bequest.’

‘Did your uncle collect all these books?’

‘Hagob? Certainly not. From what I know of him, he wasn’t entirely sane. He used to make those sculptures I mentioned - sculptures carved out of hairs under a microscope with tools of his own invention. He was known throughout the city as a crack-brained eccentric who begged food from bakers and innkeepers. Can you imagine it? There he was, sitting on this immense fortune but engraving scenes from Zamonian history on horsehairs and eating stale loaves and kitchen waste. They didn’t even find his body, just his will.’

What a story, dear readers! The last will and testament of a lunatic. The most valuable library in Zamonia far below ground. This was material that cried out to be converted into literature. The outlines of a novel took shape in my mind within seconds. My first promising idea for ages!

Smyke hauled himself up an iron handrail and looked down into a deep chasm whose walls were lined with bookshelves.

‘The owner of a house that gives access to a subterranean book cave automatically owns the cave and its contents. That rule has applied for hundreds of years, and this is the biggest cave containing the biggest collection of antiquarian books in the whole of Bookholm. It has belonged to the Smyke family from time immemorial.’

He was still staring into the depths.

‘Well, it would be fantastic enough if these books were of average quality, but they’re all literary gems: first editions, long-lost libraries, books whose existence has been in doubt for a thousand years. Many a Bookholm antiquarian would be happy to possess even one volume equal in quality to those in my collection. This isn’t just the biggest library in Bookholm, it’s the city’s greatest treasure. Several items on the Golden List are here.’

‘Aren’t you afraid someone will break in? All that stands in the way is your little house and that ridiculous lock.’

‘No, no one will break in. It’s impossible.’

‘Ah, so you’ve installed some traps!’

‘No, no traps. This cave is entirely unprotected.’

‘Isn’t that a bit . . . risky?’

‘No. And now I’ll let you into a secret: no one will break into this cave because no one knows of its existence.’

‘I don’t understand. You told me the Smykes have owned it from time immemorial.’

‘Quite so, and they carefully obliterated all trace and recollection of it over the centuries. They bribed local officials, removed entries from the land register, forged historical works and maps. They’re also said to have eliminated one or two people.’

‘Good heavens! How do you know?’

‘There are countless family papers down here - diaries, letters, documents of all kinds. You wouldn’t believe what depths of infamy they reveal. I’m not too proud of my ancestry, as I already told you.’ Smyke fixed me with an earnest gaze.

Other books

Eeny Meany Miny Die (Cat Sinclair Mysteries) by Carolyn Scott

Ms. Simon Says by Mary McBride

If Wishing Made It So by Lucy Finn

Night Tide by Mike Sherer

Sea of Lies: An Espionage Thriller by Bradley West

Crooked Little Lies by Barbara Taylor Sissel

Champion: A Legend Novel by Lu, Marie

Portraits and Miniatures by Roy Jenkins

Azrael by William L. Deandrea

His to Control (Cape Falls) by Crescent, Sam