The Code Book (19 page)

Interest increased still further when Marconi shattered the myth that radio communication was limited by the horizon. Critics had argued that because radio waves could not bend and follow the curvature of the Earth, radio communication would be limited to a hundred kilometers or so. Marconi attempted to prove them wrong by sending a message from Poldhu in Cornwall to St. John’s in Newfoundland, a distance of 3,500 km. In December 1901, for three hours each day, the Poldhu transmitter sent the letter S (dot-dot-dot) over and over again, while Marconi stood on the windy cliffs of Newfoundland trying to detect the radio waves. Day after day, he wrestled to raise aloft a giant kite, which in turn hoisted his antenna high into the air. A little after midday on December 12, Marconi detected three faint dots, the first transatlantic radio message. The explanation of Marconi’s achievement remained a mystery until 1924, when physicists discovered the ionosphere, a layer of the atmosphere whose lower boundary is about 60 km above the Earth. The ionosphere acts as a mirror, allowing radio waves to bounce off it. Radio waves also bounce off the Earth’s surface, so radio messages could effectively reach anywhere in the world after a series of reflections between the ionosphere and the Earth.

Marconi’s invention tantalized the military, who viewed it with a mixture of desire and trepidation. The tactical advantages of radio are obvious: it allows direct communication between any two points without the need for a wire between the locations. Laying such a wire is often impractical, sometimes impossible. Previously, a naval commander based in port had no way of communicating with his ships, which might disappear for months on end, but radio would enable him to coordinate a fleet wherever the ships might be. Similarly, radio would allow generals to direct their campaigns, keeping them in continual contact with battalions, regardless of their movements. All this is made possible by the nature of radio waves, which emanate in all directions, and reach receivers wherever they may be. However, this all-pervasive property of radio is also its greatest military weakness, because messages will inevitably reach the enemy as well as the intended recipient. Consequently, reliable encryption became a necessity. If the enemy were going to be able to intercept every radio message, then cryptographers had to find a way of preventing them from deciphering these messages.

The mixed blessings of radio—ease of communication and ease of interception—were brought into sharp focus at the outbreak of the First World War. All sides were keen to exploit the power of radio, but were also unsure of how to guarantee security. Together, the advent of radio and the Great War intensified the need for effective encryption. The hope was that there would be a breakthrough, some new cipher that would reestablish secrecy for military commanders. However, between 1914 and 1918 there was to be no great discovery, merely a catalogue of cryptographic failures. Codemakers conjured up several new ciphers, but one by one they were broken.

One of the most famous wartime ciphers was the German

ADFGVX cipher

, introduced on March 5, 1918, just before the major German offensive that began on March 21. Like any attack, the German thrust would benefit from the element of surprise, and a committee of cryptographers had selected the ADFGVX cipher from a variety of candidates, believing that it offered the best security. In fact, they were confident that it was unbreakable. The cipher’s strength lay in its convoluted nature, a mixture of a substitution and transposition (see

Appendix F

).

By the beginning of June 1918, the German artillery was only 100 km from Paris, and was preparing for one final push. The only hope for the Allies was to break the ADFGVX cipher to find just where the Germans were planning to punch through their defenses. Fortunately, they had a secret weapon, a cryptanalyst by the name of Georges Painvin. This dark, slender Frenchman with a penetrating mind had recognized his talent for cryptographic conundrums only after a chance meeting with a member of the Bureau du Chiffre soon after the outbreak of war. Thereafter, his priceless skill was devoted to pinpointing the weaknesses in German ciphers. He grappled day and night with the ADFGVX cipher, in the process losing 15 kg in weight.

Eventually, on the night of June 2, he cracked an ADFGVX message. Painvin’s breakthrough led to a spate of other decipherments, including a message that contained the order “Rush munitions. Even by day if not seen.” The preamble to the message indicated that it was sent from somewhere between Montdidier and Compiègne, some 80 km to the north of Paris. The urgent need for munitions implied that this was to be the location of the imminent German thrust. Aerial reconnaissance confirmed that this was the case. Allied soldiers were sent to reinforce this stretch of the front line, and a week later the German onslaught began. Having lost the element of surprise, the German army was beaten back in a hellish battle that lasted five days.

The breaking of the ADFGVX cipher typified cryptography during the First World War. Although there was a flurry of new ciphers, they were all variations or combinations of nineteenth-century ciphers that had already been broken. While some of them initially offered security, it was never long before cryptanalysts got the better of them. The biggest problem for cryptanalysts was dealing with the sheer volume of traffic. Before the advent of radio, intercepted messages were rare and precious items, and cryptanalysts cherished each one. However, in the First World War, the amount of radio traffic was enormous, and every single message could be intercepted, generating a steady flow of ciphertexts to occupy the minds of the cryptanalysts. It is estimated that the French intercepted a hundred million words of German communications during the course of the Great War.

Of all the wartime cryptanalysts, the French were the most effective. When they entered the war, they already had the strongest team of codebreakers in Europe, a consequence of the humiliating French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Napoleon III, keen to restore his declining popularity, had invaded Prussia in 1870, but he had not anticipated the alliance between Prussia in the north and the southern German states. Led by Otto von Bismarck, the Prussians steamrollered the French army, annexing the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine and bringing an end to French domination of Europe. Thereafter, the continued threat of the newly united Germany seems to have been the spur for French cryptanalysts to master the skills necessary to provide France with detailed intelligence about the plans of its enemy.

It was in this climate that Auguste Kerckhoffs wrote his treatise

La Cryptographie militaire

. Although Kerckhoffs was Dutch, he spent most of his life in France, and his writings provided the French with an exceptional guide to the principles of cryptanalysis. By the time the First World War had begun, three decades later, the French military had implemented Kerckhoffs’ ideas on an industrial scale. While lone geniuses like Painvin sought to break new ciphers, teams of experts, each with specially developed skills for tackling a particular cipher, concentrated on the day-to-day decipherments. Time was of the essence, and conveyor-belt cryptanalysis could provide intelligence quickly and efficiently.

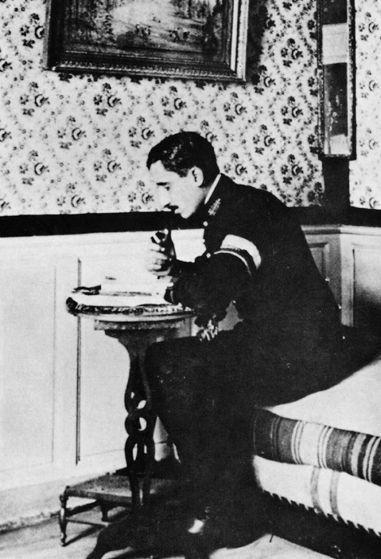

Figure 26

Lieutenant Georges Painvin. (

photo credit 3.1

)

Sun-Tzu, author of the

Art of War

, a text on military strategy dating from the fourth century

B.C

., stated that: “Nothing should be as favorably regarded as intelligence; nothing should be as generously rewarded as intelligence; nothing should be as confidential as the work of intelligence.” The French were fervent believers in the words of Sun-Tzu, and in addition to honing their cryptanalytic skills they also developed several ancillary techniques for gathering radio intelligence, methods that did not involve decipherment. For example, the French listening posts learned to recognize a radio operator’s

fist

. Once encrypted, a message is sent in Morse code, as a series of dots and dashes, and each operator can be identified by his pauses, the speed of transmission, and the relative lengths of dots and dashes. A fist is the equivalent of a recognizable style of handwriting. As well as operating listening posts, the French established six direction finding stations which were able to detect where each message was coming from. Each station moved its antenna until the incoming signal was strongest, which identified a direction for the source of a message. By combining the directional information from two or more stations it was possible to locate the exact source of the enemy transmission. By combining fist information with direction finding, it was possible to establish both the identity and the location of, say, a particular battalion. French intelligence could then track its path over the course of several days, and potentially deduce its destination and objective. This form of intelligence gathering, known as traffic analysis, was particularly valuable after the introduction of a new cipher. Each new cipher would make cryptanalysts temporarily impotent, but even if a message was indecipherable it could still yield information via traffic analysis.

The vigilance of the French was in sharp contrast to the attitude of the Germans, who entered the war with no military cryptanalytic bureau. Not until 1916 did they set up the Abhorchdienst, an organization devoted to intercepting Allied messages. Part of the reason for their tardiness in establishing the Abhorchdienst was that the German army had advanced into French territory in the early phase of the war. The French, as they retreated, destroyed the landlines, forcing the advancing Germans to rely on radios for communication. While this gave the French a continuous supply of German intercepts, the opposite was not true. As the French were retreating back into their own territory, they still had access to their own landlines, and had no need to communicate by radio. With a lack of French radio communication, the Germans could not make many interceptions, and hence they did not bother to develop their cryptanalytic department until two years into the war.

The British and the Americans also made important contributions to Allied cryptanalysis. The supremacy of the Allied codebreakers and their influence on the Great War are best illustrated by the decipherment of a German telegram that was intercepted by the British on January 17, 1917. The story of this decipherment shows how cryptanalysis can affect the course of war at the very highest level, and demonstrates the potentially devastating repercussions of employing inadequate encryption. Within a matter of weeks, the deciphered telegram would force America to rethink its policy of neutrality, thereby shifting the balance of the war.

Despite calls from politicians in Britain and America, President Woodrow Wilson had spent the first two years of the war steadfastly refusing to send American troops to support the Allies. Besides not wanting to sacrifice his nation’s youth on the bloody battlefields of Europe, he was convinced that the war could be ended only by a negotiated settlement, and he believed that he could best serve the world if he remained neutral and acted as a mediator. In November 1916, Wilson saw hope for a settlement when Germany appointed a new Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmermann, a jovial giant of a man who appeared to herald a new era of enlightened German diplomacy. American newspapers ran headlines such as

OUR FRIEND

ZIMMERMANN

and

LIBERALIZATION OF GERMANY

, and one article proclaimed him as “one of the most auspicious omens for the future of German-American relations.” However, unknown to the Americans, Zimmermann had no intention of pursuing peace. Instead, he was plotting to extend Germany’s military aggression.

Back in 1915, a submerged German U-boat had been responsible for sinking the ocean liner

Lusitania

, drowning 1,198 passengers, including 128 U.S. civilians. The loss of the

Lusitania

would have drawn America into the war, were it not for Germany’s reassurances that henceforth Uboats would surface before attacking, a restriction that was intended to avoid accidental attacks on civilian ships. However, on January 9, 1917, Zimmermann attended a momentous meeting at the German castle of Pless, where the Supreme High Command was trying to persuade the Kaiser that it was time to renege on their promise, and embark on a course of unrestricted submarine warfare. German commanders knew that their U-boats were almost invulnerable if they launched their torpedoes while remaining submerged, and they believed that this would prove to be the decisive factor in determining the outcome of the war. Germany had been constructing a fleet of two hundred U-boats, and the Supreme High Command argued that unrestricted U-boat aggression would cut off Britain’s supply lines and starve it into submission within six months.

A swift victory was essential. Unrestricted submarine warfare and the inevitable sinking of U.S. civilian ships would almost certainly provoke America into declaring war on Germany. Bearing this in mind, Germany needed to force an Allied surrender before America could mobilize its troops and make an impact in the European arena. By the end of the meeting at Pless, the Kaiser was convinced that a swift victory could be achieved, and he signed an order to proceed with unrestricted U-boat warfare, which would take effect on February 1.