The Code Book (36 page)

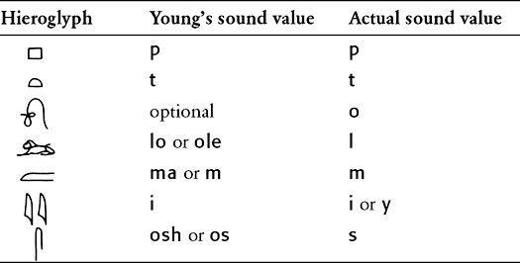

Table 13

Young’s decipherment of the cartouche of Ptolemaios (standard version) from the Rosetta Stone.

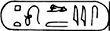

the cartouche of Ptolemaios (standard version) from the Rosetta Stone.

Although he did not know it at the time, Young managed to correlate most of the hieroglyphs with their correct sound values. Fortunately, he had placed the first two hieroglyphs ( ), which appeared one above the other, in their correct phonetic order. The scribe has positioned the hieroglyphs in this way for aesthetic reasons, at the expense of phonetic clarity. Scribes tended to write in such a way as to avoid gaps and maintain visual harmony; sometimes they would even swap letters around in direct contradiction to any sensible phonetic spelling, merely to increase the beauty of an inscription. After this decipherment, Young discovered a cartouche in an inscription copied from the temple of Karnak at Thebes which he suspected was the name of a Ptolemaic queen, Berenika (or Berenice). He repeated his strategy; the results are shown in

), which appeared one above the other, in their correct phonetic order. The scribe has positioned the hieroglyphs in this way for aesthetic reasons, at the expense of phonetic clarity. Scribes tended to write in such a way as to avoid gaps and maintain visual harmony; sometimes they would even swap letters around in direct contradiction to any sensible phonetic spelling, merely to increase the beauty of an inscription. After this decipherment, Young discovered a cartouche in an inscription copied from the temple of Karnak at Thebes which he suspected was the name of a Ptolemaic queen, Berenika (or Berenice). He repeated his strategy; the results are shown in

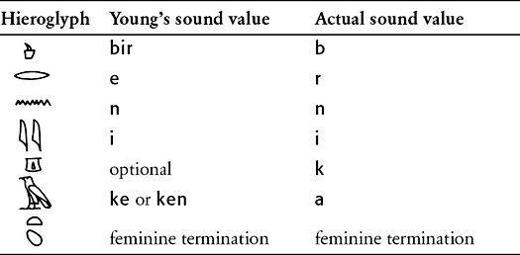

Table 14

.

Of the thirteen hieroglyphs in both cartouches, Young had identified half of them perfectly, and he got another quarter partly right. He had also correctly identified the feminine termination symbol, placed after the names of queens and goddesses. Although he could not have known the level of his success, the appearance of in both cartouches, representing i on both occasions, should have told Young that he was on the right track, and given him the confidence he needed to press ahead with further decipherments. However, his work suddenly ground to a halt. It seems that he had too much reverence for Kircher’s argument that hieroglyphs were semagrams, and he was not prepared to shatter that paradigm. He excused his own phonetic discoveries by noting that the Ptolemaic dynasty was descended from Lagus, a general of Alexander the Great. In other words, the Ptolemys were foreigners, and Young hypothesized that their names would have to be spelled out phonetically because there would not be a single natural semagram within the standard list of hieroglyphs. He summarized his thoughts by comparing hieroglyphs with Chinese characters, which Europeans were only just beginning to understand:

in both cartouches, representing i on both occasions, should have told Young that he was on the right track, and given him the confidence he needed to press ahead with further decipherments. However, his work suddenly ground to a halt. It seems that he had too much reverence for Kircher’s argument that hieroglyphs were semagrams, and he was not prepared to shatter that paradigm. He excused his own phonetic discoveries by noting that the Ptolemaic dynasty was descended from Lagus, a general of Alexander the Great. In other words, the Ptolemys were foreigners, and Young hypothesized that their names would have to be spelled out phonetically because there would not be a single natural semagram within the standard list of hieroglyphs. He summarized his thoughts by comparing hieroglyphs with Chinese characters, which Europeans were only just beginning to understand:

Table 14

Young’s decipherment of , the cartouche of Berenika from the temple of Karnak.

, the cartouche of Berenika from the temple of Karnak.

It is extremely interesting to trace some of the steps by which alphabetic writing seems to have arisen out of hieroglyphical; a process which may indeed be in some measure illustrated by the manner in which the modern Chinese express a foreign combination of sounds, the characters being rendered simply “phonetic” by an appropriate mark, instead of retaining their natural signification; and this mark, in some modern printed books, approaching very near to the ring surrounding the hieroglyphic names.

Young called his achievements “the amusement of a few leisure hours.” He lost interest in hieroglyphics, and brought his work to a conclusion by summarizing it in an article for the 1819

Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britannica

.

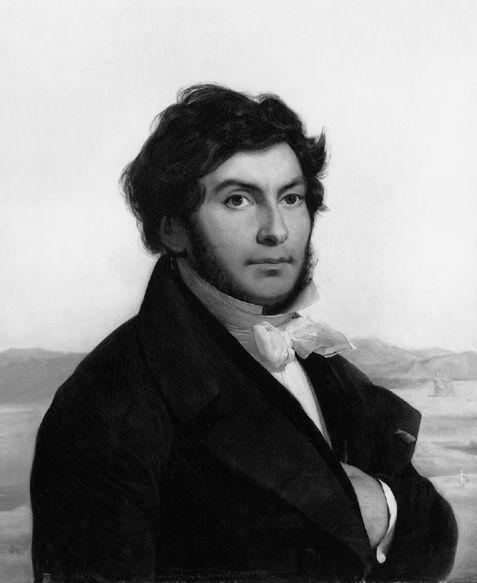

Meanwhile, in France a promising young linguist, Jean-François Champollion, was prepared to take Young’s ideas to their natural conclusion. Although he was still only in his late twenties, Champollion had been fascinated by hieroglyphics for the best part of two decades. The obsession began in 1800, when the French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Fourier, who had been one of Napoleon’s original Pekinese dogs, introduced the ten-year-old Champollion to his collection of Egyptian antiquities, many of them decorated with bizarre inscriptions. Fourier explained that nobody could interpret this cryptic writing, whereupon the boy promised that one day he would solve the mystery. Just seven years later, at the age of seventeen, he presented a paper entitled “Egypt under the Pharaohs.” It was so innovative that he was immediately elected to the Academy in Grenoble. When he heard that he had become a teenage professor, Champollion was so overwhelmed that he immediately fainted.

Figure 56

Jean-François Champollion. (

photo credit 5.3

)

Champollion continued to astonish his peers, mastering Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Ethiopic, Sanskrit, Zend, Pahlevi, Arabic, Syrian, Chaldean, Persian and Chinese, all in order to arm himself for an assault on hieroglyphics. His obsession is illustrated by an incident in 1808, when he bumped into an old friend in the street. The friend casually mentioned that Alexandre Lenoir, a well-known Egyptologist, had published a complete decipherment of hieroglyphics. Champollion was so devastated that he collapsed on the spot. (He appears to have had quite a talent for fainting.) His whole reason for living seemed to depend on being the first to read the script of the ancient Egyptians. Fortunately for Champollion, Lenoir’s decipherments were as fantastical as Kircher’s seventeenth-century attempts, and the challenge remained.

In 1822, Champollion applied Young’s approach to other cartouches. The British naturalist W. J. Bankes had brought an obelisk with Greek and hieroglyphic inscriptions to Dorset, and had recently published a lithograph of these bilingual texts, which included cartouches of Ptolemy and Cleopatra. Champollion obtained a copy, and managed to assign sound values to individual hieroglyphs (

Table 15

). The letters p, t, o, l and e are common to both names; in four cases they are represented by the same hieroglyph in both Ptolemy and Cleopatra, and only in one case, t, is there a discrepancy. Champollion assumed that the t sound could be represented by two hieroglyphs, just as the hard c sound in English can be represented by c or k, as in “cat” and “kid.” Inspired by his success, Champollion began to address cartouches without a bilingual translation, substituting whenever possible the hieroglyph sound values that he had derived from the Ptolemy and Cleopatra cartouches. His first mystery cartouche (

Table 16

) contained one of the greatest names of ancient times. It was obvious to Champollion that the cartouche, which seemed to read a-l-?-s-e-?-t-r-?, represented the name alksentrs—Alexandros in Greek, or Alexander in English. It also became apparent to Champollion that the scribes were not fond of using vowels, and would often omit them; the scribes assumed that readers would have no problem filling in the missing vowels. With two new hieroglyphs under his belt, the young scholar studied other inscriptions and deciphered a series of cartouches. However, all this progress was merely extending Young’s work. All these names, such as Alexander and Cleopatra, were still foreign, supporting the theory that phonetics was invoked only for words outside the traditional Egyptian lexicon.

Table 15

Champollion’s decipherment of and

and the cartouches of Ptolemaios and Cleopatra from the Bankes obelisk.

the cartouches of Ptolemaios and Cleopatra from the Bankes obelisk.