The Code Book (40 page)

Figure 60

Michael Ventris. (

photo credit 5.6

)

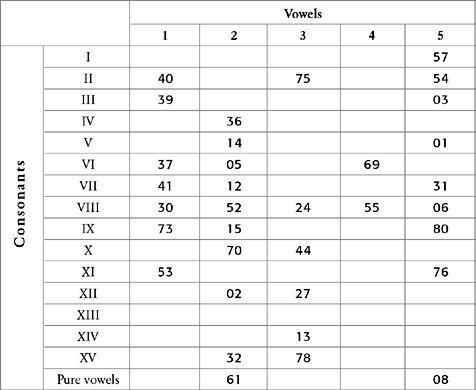

Ventris published his ideas about vowel signs, and his extensions to the grid, in a series of Work Notes, which he sent out to other Linear B researchers. On June 1, 1952, he published his most significant result, Work Note 20, a turning point in the decipherment of Linear B. He had spent the last two years expanding Kober’s grid into the version shown in

Table 22

. The grid consisted of 5 vowel columns and 15 consonant rows, giving 75 cells in total, with 5 additional cells available for single vowels. Ventris had inserted signs in about half the cells. The grid is a treasure trove of information. For example, from the sixth row it is possible to tell that the syllabic signs 37, 05 and 69 share the same consonant, VI, but contain different vowels, 1, 2 and 4. Ventris had no idea of the exact values of consonant VI or vowels 1, 2 and 4, and until this point he had resisted the temptation of assigning sound values to any of the signs. However, he felt that it was now time to follow some hunches, guess a few sound values and examine the consequences.

Table 22

Ventris’s expanded grid for relationships between Linear B characters. Although the grid doesn’t specify vowels or consonants, it does highlight which characters share common vowels and consonants. For example, all the characters in the first column share the same vowel, labeled 1.

Ventris had noticed three words that appeared over and over again on several of the Linear B tablets: 08-73-30-12, 70-52-12 and 69-53-12. Based on nothing more than intuition, he conjectured that these words might be the names of important towns. Ventris had already speculated that sign 08 was a vowel, and therefore the name of the first town had to begin with a vowel. The only significant name that fitted the bill was Amnisos, an important harbor town. If he was right, then the second and third signs, 73 and 30, would represent -mi- and -ni-. These two syllables both contain the same vowel, i, so numbers 73 and 30 ought to appear in the same vowel column of the grid. They do. The final sign, 12, would represent -so-, leaving nothing to represent the final s. Ventris decided to ignore the problem of the missing final s for the time being, and proceeded with the following working translation:

Town 1 = 08-73-30-12 = a-mi-ni-so = Amnisos

This was only a guess, but the repercussions on Ventris’s grid were enormous. For example, the sign 12, which seems to represent -so-, is in the second vowel column and the seventh consonant row. Hence, if his guess was correct, then all the other syllabic signs in the second vowel column would contain the vowel o, and all the other syllabic signs in the seventh consonant row would contain the consonant s.

When Ventris examined the second town, he noticed that it also contained sign 12, -so-. The other two signs, 70 and 52, were in the same vowel column as -so-, which implied that these signs also contained the vowel o. For the second town he could insert the -so-, the o where appropriate, and leave gaps for the missing consonants, leading to the following:

Town 2 = 70-52-12 = ?o-?o-so = ?

Could this be Knossos? The signs could represent ko-no-so. Once again, Ventris was happy to ignore the problem of the missing final s, at least for the time being. He was pleased to note that sign 52, which supposedly represented -no-, was in the same consonant row as sign 30, which supposedly represented -ni- in Amnisos. This was reassuring, because if they contain the same consonant, n, then they should indeed be in the same consonant row. Using the syllabic information from Knossos and Amnisos, he inserted the following letters into the third town:

Town 3 = 69-53-12 = ??-?i-so

The only name that seemed to fit was Tulissos (tu-li-so), an important town in central Crete. Once again the final s was missing, and once again Ventris ignored the problem. He had now tentatively identified three place names and the sound values of eight different signs:

| Town 1 = 08-73-30-12 | = a-mi-ni-so | = Amnisos |

| Town 2= 70-52-12 | = ko-no-so | = Knossos |

| Town 3 = 69-53-12 | = tu-li-so | = Tulissos |

The repercussions of identifying eight signs were enormous. Ventris could infer consonant or vowel values to many of the other signs in the grid, if they were in the same row or column. The result was that many signs revealed part of their syllabic meaning, and a few could be fully identified. For example, sign 05 is in the same column as 12 (so), 52 (no) and 70 (ko), and so must contain o as its vowel. By a similar process of reasoning, sign 05 is in the same row as sign 69 (tu), and so must contain t as its consonant. In short, the sign 05 represents the syllable -to-. Turning to sign 31, it is in the same column as sign 08, the a column, and it is in the same row as sign 12, the s row. Hence sign 31 represents the syllable -sa-.

Deducing the syllabic values of these two signs, 05 and 31, was particularly important because it allowed Ventris to read two complete words, 05-12 and 05-31, which often appeared at the bottom of inventories. Ventris already knew that sign 12 represented the syllable -so-, because this sign appeared in the word for Tulissos, and hence 05-12 could be read as to-so. And the other word, 05-31, could be read as to-sa. This was an astonishing result. Because these words were found at the bottom of inventories, experts had suspected that they meant “total.” Ventris now read them as toso and tosa, uncannily similar to the archaic Greek

tossos

and

tossa

, masculine and feminine forms meaning “so much.” Ever since he was fourteen years old, from the moment he had heard Sir Arthur Evans’s talk, he had believed that the language of the Minoans could not be Greek. Now, he was uncovering words which were clear evidence in favor of Greek as the language of Linear B.

It was the ancient Cypriot script that provided some of the earliest evidence against Linear B being Greek, because it suggested that Linear B words rarely end in s, whereas this is a very common ending for Greek words. Ventris had discovered that Linear B words do, indeed, rarely end in s, but perhaps this was simply because the s was omitted as part of some writing convention. Amnisos, Knossos, Tulissos and

tossos

were all spelled without a final s, indicating that the scribes simply did not bother with the final s, allowing the reader to fill in the obvious omission.

Ventris soon deciphered a handful of other words, which also bore a resemblance to Greek, but he was still not absolutely convinced that Linear B was a Greek script. In theory, the few words that he had deciphered could all be dismissed as imports into the Minoan language. A foreigner arriving at a British hotel might overhear such words as “rendezvous” or “bon appetit,” but would be wrong to assume that the British speak French. Furthermore, Ventris came across words that made no sense to him, providing some evidence in favor of a hitherto unknown language. In Work Note 20 he did not ignore the Greek hypothesis, but he did label it “a frivolous digression.” He concluded: “If pursued, I suspect that this line of decipherment would sooner or later come to an impasse, or dissipate itself in absurdities.”

Despite his misgivings, Ventris did pursue the Greek line of attack. While Work Note 20 was still being distributed, he began to discover more Greek words. He could identify

poimen

(shepherd),

kerameus

(potter),

khrusoworgos

(goldsmith) and

khalkeus

(bronzesmith), and he even translated a couple of complete phrases. So far, none of the threatened absurdities blocked his path. For the first time in three thousand years, the silent script of Linear B was whispering once again, and the language it spoke was undoubtedly Greek.

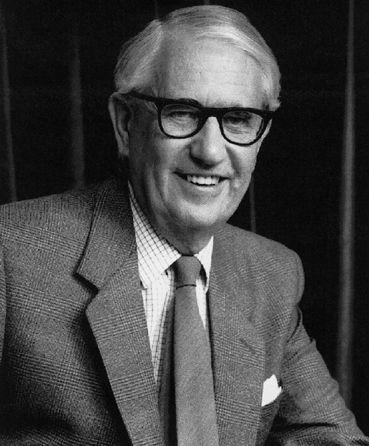

During this period of rapid progress, Ventris was coincidentally asked to appear on BBC radio to discuss the mystery of the Minoan scripts. He decided that this would be an ideal opportunity to go public with his discovery. After a rather prosaic discussion of Minoan history and Linear B, he made his revolutionary announcement: “During the last few weeks, I have come to the conclusion that the Knossos and Pylos tablets must, after all, be written in Greek-a difficult and archaic Greek, seeing that it is five hundred years older than Homer and written in a rather abbreviated form, but Greek nevertheless.” One of the listeners was John Chadwick, a Cambridge researcher who had been interested in the decipherment of Linear B since the 1930s. During the war he had spent time as a cryptanalyst in Alexandria, where he broke Italian ciphers, before moving to Bletchley Park, where he attacked Japanese ciphers. After the war he tried once again to decipher Linear B, this time employing the techniques he had learned while working on military codes. Unfortunately, he had little success.

Figure 61

John Chadwick. (

photo credit 5.7

)

When he heard the radio interview, he was completely taken aback by Ventris’s apparently preposterous claim. Chadwick, along with the majority of scholars listening to the broadcast, dismissed the claim as the work of an amateur-which indeed it was. However, as a lecturer in Greek, Chadwick realized that he would be pelted with questions regarding Ventris’s claim, and to prepare for the barrage he decided to investigate Ventris’s argument in detail. He obtained copies of Ventris’s Work Notes, and examined them, fully expecting them to be full of holes. However, within a few days the skeptical scholar became one of the first supporters of Ventris’s Greek theory of Linear B. Chadwick soon came to admire the young architect:

His brain worked with astonishing rapidity, so that he could think out all the implications of a suggestion almost before it was out of your mouth. He had a keen appreciation of the realities of the situation; the Mycenaeans were to him no vague abstractions, but living people whose thoughts he could penetrate. He himself laid stress on the visual approach to the problem; he made himself so familiar with the visual aspect of the texts that large sections were imprinted on his mind simply as visual patterns, long before the decipherment gave them meaning. But a merely photographic memory was not enough, and it was here that his architectural training came to his aid. The architect’s eye sees in a building not a mere façade, a jumble of ornamental and structural features: it looks beneath the appearance and distinguishes the significant parts of the pattern, the structural elements and framework of the building. So too Ventris was able to discern among the bewildering variety of the mysterious signs, patterns and regularities which betrayed the underlying structure. It is this quality, the power of seeing order in apparent confusion, that has marked the work of all great men.

However, Ventris lacked one particular expertise, namely a thorough knowledge of archaic Greek. Ventris’s only formal education in Greek was as a boy at Stowe School, so he could not fully exploit his breakthrough. For example, he was unable to explain some of the deciphered words because they were not part of his Greek vocabulary. Chadwick’s speciality was Greek philology, the study of the historical evolution of the Greek language, and he was therefore well equipped to show that these problematic words fitted in with theories of the most ancient forms of Greek. Together, Chadwick and Ventris formed a perfect partnership.

The Greek of Homer is three thousand years old, but the Greek of Linear B is five hundred years older still. In order to translate it, Chadwick needed to extrapolate back from the established ancient Greek to the words of Linear B, taking into account the three ways in which language develops. First, pronunciation evolves with time. For example, the Greek word for “bath-pourers” changes from

lewotrokhowoi

in Linear B to

loutrokhooi

by the time of Homer. Second, there are changes in grammar. For example, in Linear B the genitive ending is

-oio

, but this is replaced in classical Greek by

-ou

. Finally, the lexicon can change dramatically. Some words are born, some die, others change their meaning. In Linear B

harmo

means “wheel,” but in later Greek the same word means “chariot.” Chadwick pointed out that this is similar to the use of “wheels” to mean a car in modern English.