The Code Book (38 page)

After meeting various Athenian dealers in antiquities, Sir Arthur eventually came across some engraved stones, which were apparently seals dating from the pre-Hellenic era. The signs on the seals seemed to be emblematic rather than genuine writing, similar to the symbolism used in heraldry. Yet this discovery gave him the impetus to continue his quest. The seals were said to originate from the island of Crete, and in particular Knossos, where legend told of the palace of King Minos, the center of an empire that dominated the Aegean. Sir Arthur set out for Crete and began excavating in March 1900. The results were as spectacular as they were rapid. He uncovered the remains of a luxurious palace, riddled with an intricate network of passageways and adorned with frescoes of young men leaping over ferocious bulls. Evans speculated that the sport of bull jumping was somehow linked to the legend of the Minotaur, the bull-headed monster that fed on youths, and he suggested that the complexity of the palace passages had inspired the story of the Minotaur’s labyrinth.

Figure 57

Ancient sites around the Aegean Sea. Having uncovered treasures at Mycenae on mainland Greece, Sir Arthur Evans went in search of inscribed tablets. The first Linear B tablets were discovered on the island of Crete, the center of the Minoan empire.

On March 31, Sir Arthur began unearthing the treasure that he had desired most of all. Initially he discovered a single clay tablet with an inscription, then a few days later a wooden chest full of them, and then stockpiles of written material beyond all his expectations. All these clay tablets had originally been allowed to dry in the sun, rather than being fired, so that they could be recycled simply by adding water. Over the centuries, rain should have dissolved the tablets, and they should have been lost forever. However, it appeared that the palace at Knossos had been destroyed by fire, baking the tablets and helping to preserve them for three thousand years. Their condition was so good that it was still possible to discern the fingerprints of the scribes.

The tablets fell into three categories. The first set of tablets, dating from 2000 to 1650

B.C.

, consisted merely of drawings, probably semagrams, apparently related to the symbols on the seals that Sir Arthur Evans had bought from dealers in Athens. The second set of tablets, dating from 1750 to 1450

B.C.

, were inscribed with characters that consisted of simple lines, and hence the script was dubbed Linear A. The third set of tablets, dating from 1450 to 1375

B.C.

, bore a script which seemed to be a refinement of Linear A, and hence called Linear B. Because most of the tablets were Linear B, and because it was the most recent script, Sir Arthur and other archaeologists believed that Linear B gave them their best chance of decipherment.

Many of the tablets seemed to contain inventories. With so many columns of numerical characters it was relatively easy to work out the counting system, but the phonetic characters were far more puzzling. They looked like a meaningless collection of arbitrary doodles. The historian David Kahn described some of the individual characters as “a Gothic arch enclosing a vertical line, a ladder, a heart with a stem running through it, a bent trident with a barb, a three-legged dinosaur looking behind him, an A with an extra horizontal bar running through it, a backward S, a tall beer glass, half full, with a bow tied on its rim; dozens look like nothing at all.” Only two useful facts could be established about Linear B. First, the direction of the writing was clearly from left to right, as any gap at the end of a line was generally on the right. Second, there were 90 distinct characters, which implied that the writing was almost certainly syllabic. Purely alphabetic scripts tend to have between 20 and 40 characters (Russian, for example, has 36 signs, and Arabic has 28). At the other extreme, scripts that rely on semagrams tend to have hundreds or even thousands of signs (Chinese has over 5,000). Syllabic scripts occupy the middle ground, with between 50 and 100 syllabic characters. Beyond these two facts, Linear B was an unfathomable mystery.

The fundamental problem was that nobody could be sure what language Linear B was written in. Initially, there was speculation that Linear B was a written form of Greek, because seven of the characters bore a close resemblance to characters in the classical Cypriot script, which was known to be a form of Greek script used between 600 and 200

B.C

. But doubts began to appear. The most common final consonant in Greek is s, and consequently the commonest final character in the Cypriot script is , which represents the syllable se—because the characters are syllabic, a lone consonant has to be represented by a consonant-vowel combination, the vowel remaining silent. This same character also appears in Linear B, but it is rarely found at the end of a word, indicating that Linear B could not be Greek. The general consensus was that Linear B, the older script, represented an unknown and extinct language. When this language died out, the writing remained and evolved over the centuries into the Cypriot script, which was used to write Greek. Therefore, the two scripts looked similar but expressed totally different languages.

, which represents the syllable se—because the characters are syllabic, a lone consonant has to be represented by a consonant-vowel combination, the vowel remaining silent. This same character also appears in Linear B, but it is rarely found at the end of a word, indicating that Linear B could not be Greek. The general consensus was that Linear B, the older script, represented an unknown and extinct language. When this language died out, the writing remained and evolved over the centuries into the Cypriot script, which was used to write Greek. Therefore, the two scripts looked similar but expressed totally different languages.

Sir Arthur Evans was a great supporter of the theory that Linear B was not a written form of Greek, and instead believed that it represented a native Cretan language. He was convinced that there was strong archaeological evidence to back up his argument. For example, his discoveries on the island of Crete suggested that the empire of King Minos, known as the Minoan empire, was far more advanced than the Mycenaean civilization on the mainland. The Minoan Empire was not a dominion of the Mycenaean empire, but rather a rival, possibly even the dominant power. The myth of the Minotaur supported this position. The legend described how King Minos would demand that the Athenians send him groups of youths and maidens to be sacrificed to the Minotaur. In short, Evans concluded that the Minoans were so successful that they would have retained their native language, rather than adopting Greek, the language of their rivals.

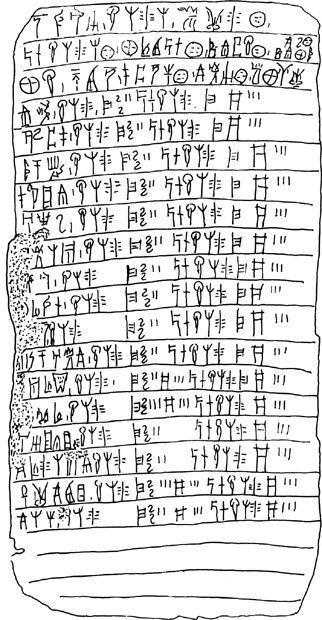

Figure 58

A Linear B tablet, c. 1400

B.C

. (

photo credit 5.4

)

Although it became widely accepted that the Minoans spoke their own non-Greek language (and Linear B represented this language), there were one or two heretics who argued that the Minoans spoke and wrote Greek. Sir Arthur did not take such dissent lightly, and used his influence to punish those who disagreed with him. When A.J.B. Wace, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, spoke in favor of the theory that Linear B represented Greek, Sir Arthur excluded him from all excavations, and forced him to retire from the British School in Athens.

In 1939, the “Greek vs. non-Greek” controversy grew when Carl Blegen of the University of Cincinnati discovered a new batch of Linear B tablets at the palace of Nestor at Pylos. This was extraordinary because Pylos is on the Greek mainland, and would have been part of the Mycenaean Empire, not the Minoan. The minority of archaeologists who believed that Linear B was Greek argued that this favored their hypothesis: Linear B was found on the mainland where they spoke Greek, therefore Linear B represents Greek; Linear B is also found on Crete, so the Minoans also spoke Greek. The Evans camp ran the argument in reverse: the Minoans of Crete spoke the Minoan language; Linear B is found on Crete, therefore Linear B represents the Minoan language; Linear B is also found on the mainland, so they also spoke Minoan on the mainland. Sir Arthur was emphatic: “There is no place at Mycenae for Greek-speaking dynasts … the culture, like the language, was still Minoan to the core.”

In fact, Blegen’s discovery did not necessarily force a single language upon the Mycenaeans and the Minoans. In the Middle Ages, many European states, regardless of their native language, kept their records in Latin. Perhaps the language of Linear B was likewise a lingua franca among the accountants of the Aegean, allowing ease of commerce between nations who did not speak a common language.

For four decades, all attempts to decipher Linear B ended in failure. Then, in 1941, at the age of ninety, Sir Arthur died. He did not live to witness the decipherment of Linear B, or to read for himself the meanings of the texts he had discovered. Indeed, at this point, there seemed little prospect of ever deciphering Linear B.

Bridging Syllables

After the death of Sir Arthur Evans the Linear B archive of tablets and his own archaeological notes were available only to a restricted circle of archaeologists, namely those who supported his theory that Linear B represented a distinct Minoan language. However, in the mid-1940s, Alice Kober, a classicist at Brooklyn College, managed to gain access to the material, and began a meticulous and impartial analysis of the script. To those who knew her only in passing, Kober seemed quite ordinary-a dowdy professor, neither charming nor charismatic, with a rather matter-of-fact approach to life. However, her passion for her research was immeasurable. “She worked with a subdued intensity,” recalls Eva Brann, a former student who went on to become an archaeologist at Yale University. “She once told me that the only way to know when you have done something truly great is when your spine tingles.”