The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (81 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

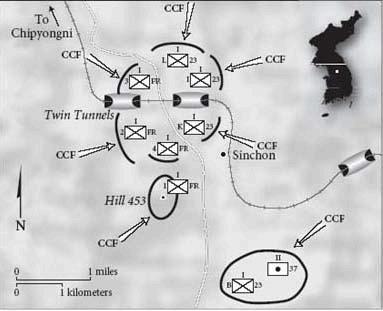

It was very fortunate that Freeman had immediately gone to the high ground and had his men prepare strong defensive positions, because his force, a little more than half a regiment with a very limited reserve, was soon hit by at least a division-sized Chinese force. “Whether the regiment could have held out that night [in the basin] at Chipyongni with only two battalions against the kind of onslaught it suffered at the tunnels is doubtful,” Ken Hamburger wrote. If the first stage of the Twin Tunnels battle had been a relatively minor battle with the survivors rescued by Tyrrell, then the second stage of Twin Tunnels was a major confrontation between a medium-sized UN unit and a much larger Chinese force with no intention of pulling back.

Both battalions of the Twenty-third were in relatively good fighting shape, at about 80 percent strength, which meant that Freeman had around fifteen hundred men committed to the battle. Against them were an estimated eight to ten thousand Chinese soldiers. His French unit was newer to the country, but its men were also fine, experienced combat troops, mostly French Foreign Legion veterans. Almost all of them were battle-tested, many already having served in Indochina, and they were led by General Ralph Monclar, one of the more charismatic figures of the Korean War. Monclar was a nom de guerre. His real name was Magrin-Vernery. He was the son of a Hungarian nobleman and a Frenchwoman, and was only sixteen when he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion (having lied about his age). He was already a sergeant when he entered St. Cyr, the French West Point. He graduated in 1914, just in time for the First World War. He had served with distinction then, and again in World War II. (When the Germans overran France, he escaped to England and led a Foreign Legion armored unit in North Africa.) He had been wounded at least thirteen times in his career, walked with a pronounced limp, and used a walking stick, which never seemed to slow him down.

By 1950, he was a three-star general, and when France decided to send a battalion to Korea under the UN flag, he asked for the right to command it, taking a reduction in rank to lieutenant colonel in order not to violate the chain of command. His superiors in Paris thought he was too old for the Korean assignment, but he felt a man was never too old to command in a cause in which he believed, and with that he won his argument. Monclar led with zest and exuberance. He thought the French, some five years into their own colonial war in Indochina, were lucky to be fighting Communism, even if it was in a far-off place like Korea. The American units came to love fighting alongside the French, because they never had to worry about their flanks. If there was one problem, it was that the French were almost too jaunty. They liked to kill with bayonets and tended to boast about it.

There had, fortunately, been enough time for the UN troops to adjust their mortars to cover likely avenues of approach. Some of the French officers, however, were nervous that their men might be too worn out from climbing to the high ground and establishing their positions. It was, of course, very cold. Freeman and Monclar, who normally got on well, squabbled over some fires the French soldiers had lit to keep warm. Freeman was appalled and called Monclar to tell him to extinguish them. Monclar said he would do it—in the morning. “Tell ’em, now!” Freeman insisted.

“But,

mon colonel,

they are such little fires,” Monclar protested.

“Big fires or little fires get ’em out, damn it, and do it now! You’ve already given your position away to every Red within a hundred miles!”

Monclar took one more shot at keeping the fires: “

Mon colonel,

it is as you say without doubt. But if they know where we are, they will attack us. Then we will kill them.” Freeman did not answer that one, and soon the French fires went out.

There was some scattered firing during the night, quite possibly Chinese probes. Then about 4:30

A.M.

the sounds of bugles and horns were heard, and the Chinese struck in force. At first nothing seemed to favor the UN force. The Chinese had the advantage of very heavy fog cover during the early hours of their attack, which allowed them to come very close to the UN positions before they could be identified; even when the fog finally lifted, the heavy overcast sky that replaced it was nearly impenetrable for air support. Freeman, hearing the first sounds of the Chinese attack, sure that it was a result of the one tank assault on Chipyongni, turned angrily to Stewart: “I told you this was going to happen.” Then he added, “What do you want me to do now?” They really didn’t have much choice, Stewart responded—it was, after all, a moment that demanded a certain fatalism: “Let’s kill as many Chinese as we can,” he said.

For the Americans it was a puzzling Chinese attack, coming so late in the morning, so many hours of darkness missed, and then continuing through the afternoon, long after the enemy normally broke contact. Later, reviewing the battle, Freeman decided that the Chinese had been caught at least partially by surprise by the appearance of such a relatively large American force and had scrambled to deny their enemies the road to Chipyongni. There were a number of signs that the Chinese were not well prepared for their attack, that it was a last-minute decision forced on them by the unexpected American move into the area. One indication was that late kickoff time, and another was the fact that the Chinese clearly lacked adequate ammunition for their heavy weapons.

21. B

ATTLE

O

F

T

WIN

T

UNNELS,

J

ANUARY

3

1–FEBRUARY

1

,

1951

The fighting was as bitter as any the Twenty-third Regiment encountered. Through much of the battle, there was a sense of what Freeman had feared from the start, the isolation of his men from the rest of the division. Ruffner, the nominal division commander, kept calling Stewart on the half hour, asking if things were really as bad as the reports he was getting. To Stewart the calls clearly reflected a lack of respect for both Freeman and himself, and showed a reluctance of Division and Corps to move instinctively to help a unit under assault. At one point when Ruffner’s doubts showed, Stewart told his superior that he was standing in the blood of his radio operator who had just been shot. Then he held the handset of the phone out the window of the hut he was in, so

that Ruffner could hear the deafening sounds of battle. Help was on the way, Ruffner then promised. Stewart said he certainly hoped so. But he was not pleased by the conversation—he was essentially being asked, in the midst of a ferocious battle, if he was really telling the truth.

Again and again the Chinese seemed ready to overrun the French and American positions. Freeman had to shift his troops constantly. He was virtually without reserves. Everyone—clerks, drivers, cooks, mechanics—had been committed, and he soon began to worry about running out of ammo—the Twenty-third had not been completely resupplied since some earlier fighting near Wonju. He and Monclar were in constant communication—by 2

P.M.

the Chinese were about to overrun one of the French strongpoints. The French company commander there, Major Maurice Barthelemy, had radioed back that he could no longer hold and had received permission to take what remained of his company and pull back. Monclar met with Freeman, and they decided to focus whatever available firepower they had on the hill where the French were embattled—the guns of their two tanks, all their available mortars, and their twin 40mm cannons—in other wars antiaircraft weapons and, in Freeman’s words, “the sweetest weapon around for vacuum cleaning a ridge.” Meanwhile, the French battalion commander told his Third Company to hold the ground they were on to the last man, no matter how many Chinese attacked. Then he planned a final desperate counterattack. For ten minutes the Americans fired every weapon they could onto the ridge. Then Barthelemy’s men charged the Chinese position with bayonets fixed. Terrified by the intensity of the attack, the Chinese finally broke and ran. Stewart, watching from the CP, was impressed. “Magnificent,” he said half to himself. Monclar, in turn, standing next to Stewart, was impressed by how cool the American general appeared, calmly smoking his pipe. “What he didn’t know,” Stewart admitted later, “was that I bit the stems off three pipes that day.”

That proved, however, only a momentary respite. Daylight it might be, but a cloudy daylight, and the Chinese, willing to take huge losses on this day, kept the battle going. By mid-afternoon, they once again appeared poised to push what was left of the UN forces off their last strongpoint, on the East Tunnel, where Item Company was positioned. The UN forces, having taken heavy casualties, were absolutely exhausted, low on ammo, and seemed not to have made a dent in the Chinese numbers. It was the low point of the day—all that valor, and they were going to be defeated anyway. The American air liaison officer standing near Stewart asked the general what was going to happen next. In about twenty minutes they would all be dead, Stewart answered. What about air support? Stewart asked him. Several flights were stacked up above them, the liaison officer answered, but they simply could not pierce the heavy

cloud cover. Just then they looked up, and a small blue patch of sky appeared right above them. Could they do anything with that? Stewart asked. The liaison officer immediately radioed the planes. “We are directly under the break and we need help!”

With that, the aircraft pounced. It was, the imperiled Americans thought, a kind of miracle. “Like a Hollywood battle,” Freeman wrote. In came the flight of Marine Corsairs, World War II prop planes first used at Guadalcanal in February 1943, and perfect for this kind of operation with their six 50-caliber machine guns, eight rockets, and room for five-hundred-pound bombs. What made them ideal for a run like this was their ability to stay over a target longer than the more modern jet fighters could. The Marine pilots circled several times to be sure they had marked the exact demarcation line between Item Company and the Chinese, then they struck. “What beautiful air support!” Freeman later wrote: first, the five-hundred-pound bombs, the daisy cutters, right on top of where the Chinese were bunched up for what would certainly have been their final assault. Then the rockets, “gook goosers” the troops called them, followed by the 50-caliber machine guns. Flight after flight struck, twenty-four in all as Freeman counted them. Finally the Chinese began to run and the battle was over. Of Freeman’s force, 225 men had been killed, wounded, or were missing. They found 1,300 Chinese bodies just along their perimeter. The total Chinese losses were placed—it was a rough estimate—at about 3,600 killed and wounded or about half of a division—the 125th Chinese Division, as they discovered from their lone prisoner. (The fighting had been too intense to take more, and he had been badly wounded.) That division was part of the Chinese Forty-second Army. For weeks Matt Ridgway had been looking for the Forty-second Army. Now Paul Freeman had found it for him.

IN THE LATE

afternoon, the Air Force air-dropped more ammo and other supplies in, and a relief force, the First Battalion of the Twenty-third, which had marched all the way, finally arrived. Freeman and Monclar remained nervous that the Chinese might strike again that night. But for the time being the Chinese were through. The regiment spent the day consolidating its position and then, on February 3, got its next assignment—to advance on Chipyongni, about four miles away, and occupy that critical village.

C

HIPYONGNI TURNED OUT

to be the battle Matt Ridgway had wanted from the moment he arrived in country. It was one of the decisive battles of the war, because it was where the American forces finally learned to fight the Chinese. For years after, what Paul Freeman did there was studied at the Command and General Staff School at Leavenworth as a textbook case of how to deal with a numerically superior enemy. Turning point though it was, like other battles in Korea it was rarely known outside the world of the men who fought there, or the military men and scholars who studied the history of the war. But at that small village the almost mythical sense of Chinese superiority, perhaps even invincibility, came to an end. By then, a mordant humor had emerged among the soldiers when it came to the Chinese and how many there were likely to be in battle: “How many hordes to a platoon?” went one line; “I was attacked by two hordes yesterday and killed both of them” went another. When Chipyongni was over, there was a new sense, not just among the commanders but among the fighting men themselves, that if they held the right positions with the right fields of fire and had the right leadership, the burden of battle would be on the less heavily armed Chinese. Equally important, when it was over, the Chinese knew it too.

Chipyongni was one of those many small Korean villages that war celebrates as peace does not. It was fairly typical for the country—a mill, a school, and a Buddhist temple. Along the main street ran a small stream. All in all, it was not much, at least by Western standards. By the time the Twenty-third Regiment arrived to take up its positions, the mill had been demolished, the school and the temple destroyed, and most of the villagers were gone. In that way it was also all too typical of the Korean countryside of that moment—competing armies came and went in this war, and every time one of them arrived, there was less of the village left. But to both sides it had a disproportionate strategic importance, because it controlled passage—by rail east and west, by road north and south—through the central part of the country, where there were few other routes of any consequence.

To the surprise of Freeman and his men, they entered Chipyongni without opposition. For whatever reason, the Chinese, who were moving a great many men around in the sector, let the Americans take it unchallenged. Though his defense was eventually cited as a textbook case in the use of limited forces, in the beginning Paul Freeman was not entirely pleased with his situation. He would have greatly preferred, as he told Captain Sherman Pratt, to hold a series of hills around the village that were much higher than those he finally settled on, but given the limited number of men at his disposal, his forces would have been spread too thin if he had. His very first decision was subsequently viewed by experts in infantry tactics as unusual, but in the end brilliant. The most basic rule for an infantry commander, especially one contemplating a defensive stand against an enemy with vastly superior numbers, is to hold the high ground. Nominally the higher hills or mountains in that area would have created an almost impregnable defensive barrier. But to man them would have necessitated a ridgeline defense some twelve miles long, and a perimeter with a four-mile diameter, which would have required a division, not a regiment. A perimeter that large might have been a much easier one for the Chinese to break through at key points, rolling the entire defensive line up as they preferred to do.

So Freeman wisely chose to concentrate his defense on the smaller but closer hills. That gave him a rectangular defensive perimeter only one mile in depth by two miles in length. On almost all sides he held ground high enough to present serious problems for any attacking troops. In a way he was setting up the kind of defense that a good many American commanders had been pondering since they were first hit by the Chinese along the Chongchon. No less important was what he was

not

doing. He was not preventing his heavier guns from supporting one another; he was not making it impossible for one of his reserve units to come quickly to the aid of a troubled position.

He was also, he hoped, exploiting a great weakness of the Chinese, their lack of heavy artillery pieces. The Chinese would hold the distant higher ground, to be sure, but the Americans would have the advantage in long-range artillery. As for machine guns, the Chinese would have plenty of them, but planted on the distant higher ground they would be of little or no value. The Chinese, he had to expect, would have mortars and would surely use them well. But perhaps UN airpower would be able to take some of them out, if the weather broke just right. The other crucial advantage that Freeman had was time. He was the first American commander to have the luxury of time in this new war and some idea of what to do with it. His troops arrived in Chipyongni on February 3; the Chinese attack did not come until the evening of February 13: ten precious days to prepare his positions. Every man in the Twenty-third

was aware of the regiment’s vulnerability and that their lives depended on how well they dug in (though the Army historian Roy Appleman walked their foxholes in August 1951 and was surprised that they were not deeper). Fields of fire were measured for mortars and artillery pieces, marking precisely all potential avenues of approach. Barbed wire was strung until it ran out. Mines were planted until they had no more of them. A small airstrip was cleared, which would allow them, if need be, to bring in supplies and evacuate the wounded.

For the first time, Freeman believed that he had almost too much ammunition. On that, he learned soon enough, he was wrong. Spotter planes flew overhead every day trying to pick up any Chinese movements in the surrounding hills. Every day, Freeman sent recon patrols out, trying to find out what the Chinese were up to. As the days passed, and they got closer to the Chinese D-day, there was just one hitch. In a battle that was both separate and yet

very

connected, ROK forces attacking north from nearby Wonju, about ten miles to the south and east, had collapsed, and American and Dutch forces fighting with them were now in danger of being overrun and annihilated. The drive of UN forces north of Wonju that had begun on February 5 was by February 14 going very badly. The ROK advance that had initiated the larger battle on Wonju was, a number of senior people in the division, including George Stewart, believed, part of an ill-conceived, almost bizarre Almond plan. He had sent the ROKs north as the lead element, which had amazed everyone. When the Chinese struck the ill-prepared ROKs—and estimates were that there were four Chinese divisions operating in the Wonju area—they had quite predictably destroyed the ROKs, and it had opened up vast avenues for the Chinese into the American and Dutch forces. That greatly endangered the entire Wonju area, and quite possibly Chipyongni as well. Thus even before the battle of Chipyongni began, its defenders were in ever greater jeopardy. Not only did the battle of Wonju have a priority on any call for airpower, but there was now a fear that unless the balance at Wonju was redressed, the Chinese might soon be free to throw even greater forces, perhaps four more divisions, at Freeman.

By February 10, the small patrols that Freeman was sending out had determined that the area was swarming with Chinese and his terrain was shrinking by the hour. That Paul Freeman is now considered one of the three or four most distinguished regimental commanders of the Korean War, his reputation based largely on his performance at Chipyongni, is not without considerable irony. For in the days immediately preceding the battle, he wanted badly to pull back, fearing the immense buildup of Chinese all around his perimeter. By February 12, it was clear to him that his men were soon to be encircled by an overwhelming force. That was bad enough. Worse yet, American forces in two

of the Thirty-eighth Regiment’s battalions were being cut up just north of Wonju, and it was possible that the rest of Tenth Corps might not be able to hold the town itself. Already two relief forces sent out to reinforce Freeman, one of them the British Commonwealth Brigade, had been hit hard and found themselves unable to break through. To Freeman, his lonely salient facing what seemed to him like all the Chinese ever sent to Korea was “sticking out like a sore thumb.”

When he asked for permission to pull back, he was told that Ridgway wanted him to stay put. As the moment when the Chinese would attack grew even closer, all the senior officers of the Twenty-third knew that some kind of argument was going on at a pay level far above theirs. All the other UN units in the area were pulling back—but not the Twenty-third. Their orders on February 12, as recorded by the regimental operations officer, were to stay put: “We are to remain. By order of Scotch.” (Scotch was the code name for Ridgway.) On that same day, Major John Dumaine, the regimental operations officer, told Captain Pratt that Freeman wanted to pull back, but he was doubtful they would be able to get out now, partly because of the masses of Chinese moving in around them: “I don’t think we could withdraw now if we wanted to. The latest report by Shoemaker [Major Harold Shoemaker, the regimental intelligence officer, who would die at Chipyongni] is that the road south, our only avenue of escape, is already swarming with Chinese and is closed. Even if we got permission to withdraw, we would have to fight another gauntlet to get out. I think we are going to stay and fight it out.” That seemed to seal it; a siege was already on and airdrops of supplies already taking place. For those at Chipyongni, their destiny, they now knew, was something they would have to determine themselves. They were on their own.

But Freeman and Ruffner at Division still hoped to get their orders changed. Even Almond agreed, in part because of the growing failure of other units under his command. Almond had flown in to meet with Freeman around noon on February 13, aware that the battle around Wonju was going very badly, which placed Chipyongni in even greater jeopardy. He found Freeman anxious, talking about the possibility of losing his entire regiment in this battle. Freeman asked for permission to withdraw on the morning of the fourteenth. He wanted to retreat to Yoju, about fifteen miles south, even though there was an increasing likelihood that the Chinese had cut the road. His position, he said, was very fragile. He had the approval of Ruffner, the division commander, to move back, and now Almond seemed to agree as well.

Inside the Twenty-third perimeter, word got around very quickly that they were going to pull back. In fact the commander of the RCT (Regimental Combat Team) antiaircraft battery, sure that they were soon to retreat and believing

he had too much ammunition to take out with him, asked for permission to fire some of it into the distant hills. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Meszar, the regimental executive officer, told him to wait another day just to be sure. By the time Almond got back to his corps headquarters, Freeman had changed his mind—he no longer felt he could wait an additional day and wanted to go out on the thirteenth. Right after his meeting, Freeman sent a message to Division headquarters: “Almond here about 1

1

?2 hours ago, asked my recommendation when I could move back to Yoju. I told him in the morning. I have changed my recommendation to as early as possible this evening…. Pass this request to CG Xth Corps and relay answer to me as soon as possible.” Now the decision belonged to only one man, the man who had wanted this particular battle in the first place. Ridgway remained immune to additional pleas from inside Chipyongni. What he did promise was that, if Freeman stayed and fought, he would make sure a relief force punched through. If need be, he said, he would send the entire Eighth Army to rescue them.

As an old airborne man, he was convinced that Freeman’s troops, well dug in and with a good deal of firepower, could be resupplied with ammunition and other needs by air. This then was the test battle he had been hoping for; imperfect perhaps, but one never got the perfect battle. It pitted, if things worked out, superior U.S. firepower against superior numbers, in a venue more or less chosen by the Chinese rather than by us, and as such ought, Ridgway hoped, to be a litmus test for the rest of the war.

Sometime in the late afternoon of the thirteenth, Sherman Pratt visited Freeman and found him fatalistic. Freeman showed Pratt a map that reflected their complete encirclement by perhaps four divisions of Chinese troops, he said. He told Pratt simply, “If they [the Chinese] want it, they are going to have to come and fight for it. I think we are ready—that we can fight well where we are now.” Early on the evening of the thirteenth, Freeman called his commanders together. There had been a lot of talk about pulling back, he said, but it wasn’t going to happen. “We’ll stay here and fight it out.” He wanted every commander to check each foxhole and each field of fire one last time. The attack, he said, might come that night.

He had placed the First Battalion on the northwest sector, the Third Battalion on the northeast and east sectors, the French battalion to the west, and the Second Battalion to the south. He had some fifty-four hundred men under his command, a beefed-up regiment, a regimental combat team. The Chinese, it was believed, had elements of five divisions, a force of perhaps thirty to forty thousand men. Chipyongni was to be not just a battle but a siege. The only way for Freeman’s forces to get more ammo and food was by parachute airdrops.