The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (27 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

Literature and Culture of the Republic

In This Chapter

- The growth of Latin literature

- Roman attitudes toward literature

- The Golden and Augustan Ages of Latin literature

- Principle authors of Latin literature

Most people are more aware of Roman conquest than they are of Roman (Latin) literature. That's a shame. Latin literature is rich and complex, influential and well worth the effort. But compared to Roman conquests, Latin literature had a late start: It didn't get going until the second century

B

.

C

.

E

. and came into its own in the first century

B

.

C

.

E

. In the time of Augustus (63

B

.

C

.

E

.â

C

.

E

. 14), it flourished into a supernova, burned bright through the first centuries, and slowly faded until Boethius's

Consolation of Philosophy

but twinkled from his prison cell into the approaching dark ages.

In this chapter, we'll look at the rise and development of Latin literature and culture through the end of the Republic and the Augustan Age. I've chosen to tell you this story through short biographies of six writers from each period. You can pick up the literary story from where this trail leaves off in Chapter 21, “

Cogito Ergo Sum:

The Life of the Mind.”

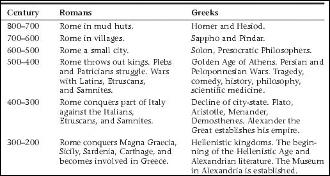

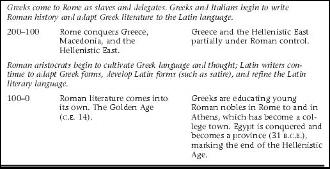

When thinking about Latin literature and culture in time, it's interesting to compare it to a rough timeline of Greek literature and culture.

As you can see, Roman literature doesn't really begin until the second century

B

.

C

.

E

. There are several reasons for this late start. First, literary culture needs a certain

amount of stability, time, and critical mass that the Romans just didn't have until they had established their presence broadly across Italy. Second, literary culture needs cultural place and value. High literature and culture weren't a part of the general Roman self-image nor were they among the values of the aristocracy (the class that typically cultivates literary pursuits). The

last

thing a Roman noble wanted to be known for was sitting around thinking and writing. Romans increased their political power, wealth, and

auctoritas

and

dignitas

. Romans, well,

did

things.

Â

Veto!

It's simplistic to say that the Romans copied or borrowed all their literature and culture from the Greeks. Romans decidedly had their own culture. Their literature developed from Greek models, but it, too, became uniquely “Latin” and “Roman.” To say otherwise would be like claiming that contemporary Americans have no literature or art of their own because it has roots in European and African cultures.

Â

When in Rome

Tragedy

(a play about inescapable and inordinate suffering brought on by the human condition) and

comedy

(a play about the humorous interaction of people, events, and ideas) were invented by the ancient Greeks and came into full development in Athens during the fifth century

B

.

C

.

E

.

Consequently, during the conquest of Magna Graecia and Greece, Latin literature was mostly the work of ethnic Greeks from southern Italy. Writers began to compose the kinds of works that their conquerors wanted: translations of Greek works, comedies to entertain, and histories that took the Romans into account. Some of the important early writers were . . .

- Livius Andronicus

(284â204

B

.

C

.

E

.), a Greek from the captured city of Tarentum. As a captive, Andronicus translated Homer's

Odyssey

into Latin according to a native Latin meter, and adapted Greek comedies and tragedies to Latin but kept Greek costume. Only about 100 lines of his work remains. - Cornelius Naevius

(270â201

B

.

C

.

E

.), a Roman plebeian who wrote comedies and plays on historical themes and used Roman costumes. Naevius got into trouble for his political attacks on the nobility and died in exile. He also wrote a patriotic Roman epic in Latin meter about the first Punic War. No work remains. - Titus Maccus Plautus

(254â184

B

.

C

.

E

.), a great Umbrian comic playwright and lyricist. Roman literature really begins with Plautus. About 20 of Plautus's comedies surviveâall versions and adaptations of ancient Greek “New Comedy” (a combination of sitcom, musical theater, and vaudeville). Plautus's

wordplay, themes, and humor are decidedly Roman in sensibility and make for great reading. - Quintus Ennius

(239â169). If you asked the Romans who was the father of Latin literature, Romans would point to Ennius. Ennius was from southern Italy in Calabria. He was trilingual, saying that he had three hearts: one Oscan (his native tongue), one Greek, and one Latin. Ennius was famous for his wit and learning, for adapting the Latin language to Greek epic and elegiac meters, and for making an epic of Roman history. He wrote tragedies, comedies, and other minor works, but his greatest achievement was the

Annales,

a patriotic epic reaching from mythological antiquity to the events of his own day. The

Annales

also featured portraits of famous Romans and their virtues; it was a foundation text of Latin school learning and influential on later Roman epic and history. Only fragments of Ennius's work survives. Ennius was connected with prominent Romans of his time. He was brought to Rome by Cato the Elder to lecture and accompanied his patron, Marcus Fulvius Nobilior, on a campaign in Greece to write about his patron's achievements. Through these and other connections, Ennius was awarded Roman citizenship.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Hint: Want to see something really close to a Plautine comedy? Rent yourself a copy of

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,

which comes complete with music, dance, stock characters, and the three-house set. Want something a bit more literary? Try Oscar Wilde's

The Importance of Being Earnest.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Think the

Simpsons

are something new?

Au contraire.

Situation comedy began in Greece in the fourth century

B

.

C

.

E

. and came to its high point in the Greek comedies of Menander (342â292

B

.

C

.

E

.) and the Latin comedies of Plautus. Menander's plays featured funny situations and stock family characters that everyone could recognize. There was the

senex

(old man), usually the crabby, stingy, lustful father of the family, or the

matrona

(woman), his nagging and worried wife. Plautus's comedies featured a stock set of three buildings and a long stage on which characters sing, dance, interact, escape, or overhear one another without exits.