The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler (4 page)

Read The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

The Strellbriggs’ attitude surprised Jane; they seemed indifferent to the anguish that they and their daughter were causing. Jane tried to interrogate them about their daughter’s possible whereabouts and what might have happened to her, but they were quite unhelpful. The Major at one point said that it was ‘a rum go’, and Daphne remarked that it was ‘most odd’, but that was the extent of their reaction. When they arrived towards evening at Lockington Magna, Jane found Mrs von Hohenheim’s bungalow locked and dark. She fetched a torch from the car and shone it through the windows. The house was not only deserted, it was empty: not a single item of furniture could be seen.

Jane wanted to scream loud and long, but she did not because she knew it would upset her mother. She steadied herself, returned to the car, got in and explained the situation to the Strellbriggs. The Major once again said that it was ‘a rum go’ at which Jane felt a strong desire to get the Strellbriggs out of the car with the luggage and leave them there stranded. Restrained by fifty or so years of self-sacrifice, she drove them back to her home. Repeatedly she asked them about their daughter, but the Strellbriggs’ ignorance or reluctance to communicate was phenomenal. The only fact that they were able to vouchsafe was that her husband Mr von Hohenheim had died many years ago.

In exasperation Jane asked if Mrs von Hohenheim really was their daughter.

‘Oh, yes!’ said the Major. ‘Daphne had her out in Africa. Funny little thing she was: looked like a monkey. Do you remember, Daphne, we used to call her “little monkey”?’

‘Little Monkey,’ said Daphne fondly.

‘And good old Pigby stood godfather at the christening in Kampala Cathedral. Gave her a mug made out of rhino horn.’

‘What is her Christian name?’ asked Jane who felt that these reminiscences had got out of hand.

‘Molly. No! Magda,’ said the Major.

‘No, Molly,’ said Daphne.

‘Well, she’d answer to “hi!” or any loud cry, as they say,’ said the Major with an ugly catarrhal chuckle. After that, the Strellbriggs lapsed into silence and would only respond to Jane’s questionings with the briefest of monosyllables. So she gave up.

**

It was a sleepless night, but fortunately one undisturbed by mysterious noises. The following morning, as soon as she could, Jane began to ring the offices of OPEN, demanding to speak to Martha Wentworth-Farrow. Mrs Wentworth-Farrow heard her out and expressed the deepest sympathy.

‘What are you going to do about it?’ demanded Jane.

‘Well, of course, we’ll do all we can. We’ll make enquiries immediately.’

‘Don’t you think that the time for enquiries was before you put Mrs von Hohenheim on your books?’

‘We don’t use references, as you know,’ said Mrs Wentworth-Farrow. ‘We operate on the principle of trust.’

‘A principle which in this instance has served you very ill,’ said Jane who liked the occasional literary turn of phrase. Even in these appalling circumstances she derived some satisfaction from scoring over Mrs Wentworth-Farrow.

‘Please do not take that attitude, Jane. It is very unhelpful.’ This attempt to regain the high ground failed. Jane simply rang off.

In the afternoon Jane rang the police. A pleasant policewoman came round to interview the Strellbriggs who were, as usual, genial but unhelpful. The policewoman recommended that Jane should ‘get on to the Social Services’. Jane did as she was told but was informed that a social worker was not available at the moment, and because this was not an emergency, she was not likely to receive a visit for another couple of days. Then Mrs Wentworth-Farrow rang to say that she had ‘done what she could’, which was to find out that the house in Wiltshire had been rented on a six month’s tenancy by a Mr Villach, that no references had been given as the rent had been paid in advance to the agent, and that no forwarding address had been given. Moreover, there seemed to be no records of anyone of the name of either Villach or von Hohenheim or Strellbrigg existing in this country. Jane asked Mrs Wentworth-Farrow what she was going to do about this mess, to which Mrs Wentworth-Farrow replied that while she was doing all she could, the responsibility of her organisation did not extend beyond the periods during which the exchange of old people took place. Jane once more put the phone down. It immediately rang again, the caller this time being her brother Tony making his regular monthly enquiry after his mother. Taken off guard, Jane told him about her difficulties to which Tony responded by saying that if only she had consulted him before embarking on the venture, he ‘personally’ (a favourite word of his) would have advised against it. He also recommended that she should ‘get on to a solicitor and sue Mrs Wentworth-Farrow’.

Meanwhile the Strellbriggs were in her living room calmly consuming large quantities of tea and Bourbon biscuits. Their equanimity in Jane’s eyes amounted to a kind of madness, or pathological callousness at the very least.

That night the house was once more full of noises until about three in the morning when it suddenly became quiet. In the silence that followed, Jane’s ears, attuned by rage and anxiety to an abnormally high degree of sensitivity, caught the faint creak of a window being opened in the sitting room which was below her bedroom. She went to her own window and looked out.

In the yellow glare of street lamps she saw a large, crouched shape in striped pyjamas climb out of her sitting room window. It was bent low so that its hands almost touched the ground. She could not see the face, only the back of its head on which wayward, uncombed grey hairs stuck out in all directions. It shambled across the front lawn, moving crookedly yet with some fluidity; then, instead of passing through the front gate, it scrambled awkwardly onto the low garden wall and wriggled through a gap in the privet hedge. Once behind the privet hedge Jane could no longer see it, but it must have passed along the other side of the wall, still crouched low, until it was out of sight from the house.

Jane felt her heart beating fast. A detached part of her worried that what she had seen would give her a heart attack; and then what would become of mother? What had she seen? It must have been the Major, except that it did not quite look like him, and certainly the creature’s movements were not those of a ninety-year-old man.

The thumping of Jane’s heart made her so breathless that she had to sit down on the bed. At some point after that she fainted. When she came to there was a hint of early morning in the sky. Jane listened for noise, but there was none. She went downstairs and into the sitting room. All windows were closed and bolted on the inside. She told herself that she had had a peculiarly vivid dream, but she lied.

The following day a social worker called Lorna came. She asked a great many questions and wrote down the answers on a notepad attached to a clipboard. Jane thought that she had been interrogated rather aggressively, as if she was to be held responsible for the situation. After this Lorna insisted on interviewing the Strellbriggs alone.

When Lorna came out of that meeting Jane saw confusion and shock on her face.

‘Did you get anything out of them?’ she asked.

Lorna took her notes off the clipboard and placed them in a large straw bag. ‘Mrs Capel,’ she said. ‘I will have to go back and discuss the case with my colleagues. We’ll get back to you as soon as possible.’

‘When?’

‘Our guidelines are to respond to these situations as soon as possible, Mrs Capel.’

‘In the meanwhile what do we do about them? I have two strange, unwanted old people cluttering up my house. I’m perfectly within my rights to turn them out onto the street.’

‘I’m sure you don’t want to do anything like that, Mrs Capel.’

‘But what are you going to do about it?’

‘Now, Mrs Capel. We will be prioritising your dilemma here, but I have to review the situation, discuss the case with my colleagues. I do assure you, I will be getting back to you as soon as possible.’

At that moment Jane hated Lorna, with her complacent professionalism, her fat, bespectacled face, her dreadful taste in jewellery, more than she had hated anyone since her schooldays. More than the Strellbriggs? Certainly. Jane found that she could no more hate them than she could the wind and the rain, or her poor crazed old mother. The white heat of her rage stifled all speech. She saw Lorna to the door in silence. Just before she left Lorna turned to Jane and, pointing to the sitting room where she had just interviewed the Strellbriggs, she said:

‘Mrs Capel, I have just been called a black bitch in there by that man. Now I don’t have to put up with that sort of thing. You won’t understand how much that hurts; but I tell you, I will do the best for you and your case, but I am not coming back into this house ever again.’ And with that, she left.

Jane rang up her solicitor and arranged to see him the following morning.

**

Normally Jane would not have left her mother in the care of the Strellbriggs for more than an hour at most, but she was past caring. She had to go into central London to see Mr Blundell, whose firm had dealt with her family’s affairs for years. Mr Blundell listened to Jane’s story with enormous professional sympathy. Could she sue Mrs Wentworth-Farrow? Possibly, but the expense might be prohibitive. Did she have the right simply to evict the Strellbriggs? Possibly, but then again. . . . He would have to do some research into that.

Jane came away from her meeting unsatisfied, but oddly soothed. She felt that Mr Blundell, however ineffectually, had been wholly on her side. She returned to Westwood rather late and found her guests the Strellbriggs waiting expectantly for lunch. For some minutes she was so preoccupied that she failed to notice that her mother was not with them.

‘Where’s mother?’ she asked eventually.

‘Oh,’ said Daphne. ‘Has she gone?’

‘Of course she’s gone. She was here in the sitting room with you. Did you put her back to bed or something?’

‘Why would we want to do that?’ said Daphne.

Jane looked all over the house. Everything that belonged to her mother was there but not her mother. When Jane returned to the sitting room she asked the Strellbriggs again where her mother was.

‘Haven’t an earthly,’ said the Major from behind his

Telegraph

.

‘Neither have I,’ said Daphne. ‘Awfully sorry.’

Jane stared at them. It was extraordinary how well and placid they looked. Their flesh had filled out; it was pink and unwrinkled.

‘Look. She was here with you when I left this morning. She can’t have just gone out without you noticing. Dammit, she can barely walk.’

‘Aha!’ said the Major. ‘The great disappearing mother mystery!’

‘It is

not

funny!’ replied Jane, stamping her foot, the tears starting from her eyes.

She went out into the street and looked up and down. Her mother could not have gone far. She searched the street, knocked on doors and asked neighbours. No-one had seen her, and Jane was getting suspicious looks. Someone asked: ‘Are those friends still with you, then?’

‘They are NOT friends!’ said Jane with a violence which startled even herself. More suspicious looks followed.

After two useless hours, she returned to her home to find that the Strellbriggs, together with all their bags and property, had also gone. She telephoned the Police.

The Police responded surprisingly quickly to Jane’s call and sent two men round, a Sergeant and a young Constable. As the Sergeant sat very patiently listening to the whole story, the Constable began a rather desultory search of the house and garden. Suddenly Jane and the Sergeant heard him cry out from the back yard.

They found him leaning against a wall, pale and in a state of shock. He pointed to something lying beside one of the dustbins. It appeared at first sight to be a withered and desiccated chipolata sausage. One end, a tangle of dark brown sinews and gristle, looked as if it had been chewed; at the other end were the chalky remnants of a finger nail. The object was still loosely encircled by Jane’s mother’s engagement ring.

The Sergeant lifted the lid of the dustbin, looked inside, and then replaced the lid very rapidly. Before Jane fainted, the last thing she remembered was the sensation of seeing stars explode in front of her eyes.

THE GARDEN OF STRANGERS

I was ambitious; that is why I wanted to meet him. I cannot honestly say that I felt compassion for the man, though now, fifty years after, I have come to believe that he deserved it.

It was in the summer of 1900, the year of his death, that I sought him out. I knew he was in Paris and, armed with that information alone, I made my way there. For a man so universally shunned he was surprisingly easy to find. It was all quite deliberate and coldly calculated on my part. I would offer to buy him dinner; he would accept out of necessity; I would then write the article for the

New York Sun

(with which I had some connections), and it was to make my name as a journalist. I even had a title fixed up; it was to be called: ‘I had dinner with Oscar Wilde’. I thought that was neat.

But somehow I never got to write the article, though I did have dinner with him. I’d like to say it was some kind of delicacy that prevented me, but I don’t think so. I funked it, I guess, and it’s only now that I can look at my efficient shorthand notes—made, it seems, by a stranger—and set down my account. Maybe it’s because Death is looking me in the eye, just as, fifty years ago, He was looking at poor Oscar.

Oscar used to say that when good Americans die they go to Paris. I don’t know about that—not just yet—but I do know that way back in 1900, there was quite a set of live Americans there who stuck together and prided themselves upon their cosmopolitan sophistication. They knew all about Oscar, though most of them kept their distance, as in those days he was still looked on as some kind of contagious disease. But someone put me in touch with the writer Vincent O’Sullivan who was American born, and he knew Wilde pretty well. He gave me some searching looks, but I told him I was an admirer who wanted to meet his hero. He just nodded: ‘You can usually find him every morning between eleven and one at the Café des Deux Magots on the Left Bank.’ So I thanked him and the next morning I headed off to that café.

He was not hard to recognise, even though the figure I saw was very unlike the photographs of him in his gorgeous heyday. There was something about the way he sat at the table outside the café that alerted me to a presence before I could even make out his features, that ‘curious Babylonian sort of face’, as someone once described it to me. He was sitting very upright, a glass of greenish liquid—chartreuse or absinthe?—on the table in front of him, and he seemed to be looking intensely at the crowd. As I discovered later this was not the case: his eyes were turned inwards on his own unhappy dreams. His right arm was stretched out horizontally, his large, clumsy hand resting on the gold head of a stout malacca cane. The pose was regal. He was kind of portly and, but for his subtle air of distinction, one might have taken him for a banker, or a financier taking a morning off from the Bourse.

I had expected someone shabby and down at heel, but he wasn’t. He was very tidily dressed, though not exactly smart. Only when you looked close did you see that his cuffs were frayed and there were one or two tiny patches in his frock coat. I approached him and introduced myself as Jonah P. Ellwood, a friend of Vincent O’Sullivan (not strictly true), and a fervent admirer of Oscar Wilde (not strictly true either).

‘Any admirer of Oscar Wilde is a friend of mine,’ he said.

I duly laughed and I could tell he was pleased, but did not flatter myself that it was anything to do with me personally. I was company, that was all.

‘Mr Wilde, I would like to invite you to have dinner with me,’ I said.

‘My dear Mr Ellwood, you look far too young and indigent to be taking Oscar Wilde out to dinner at an expensive restaurant. I will take

you

out to dinner.’

Just imagine my delight!

‘However,’ he went on. ‘In order for me to do so, I shall require a small loan from you of a thousand francs.’

I hesitated for a moment. A thousand francs was a lot of dough, but I knew I could get a good return on my investment, so I arranged to meet him at the café that evening with the thousand francs. I may have been a greenhorn, but I wasn’t such a greenhorn as to expect that I would ever get the loan back. As Oscar said when we took our temporary leave: ‘Your reward will be in heaven, my boy.’ Then he added, characteristically: ‘Where mine will be is rather more problematic.’

That evening we met at the Café des Deux Magots where I handed him the one thousand francs. As soon as I had done so he became anxious that we should be on our way.

‘We will not go to Maxim’s or anywhere like that,’ said Oscar. ‘I know a place that is quite exquisite and even more costly: Bignon’s. We shall have a private room. They know me well there: in fact they know me so well that, out of courtesy, they always fail to recognise me. I who was once a votary of fame now worship anonymity. My reputation no longer precedes me; it dogs me like a shadow. Take my advice, my boy, and never become notorious: it is so horribly expensive.’

With an imperious gesture he summoned a fiacre which he ordered to take us to Bignon’s. When we were in the carriage he said: ‘After we have dined, I shall tell you all the dreadful secrets of my hideous life. That is what you want me to do, isn’t it?’

I tried to offer up some protest, but he waved it aside.

‘No, no. I could tell at once that you were a perfectly normal healthy young man and therefore eager to learn every sordid detail. It is quite natural. We love to contemplate the vices to which we have never been tempted. I, for instance, am always anxious to learn everything I can about the selling of insurance. It seems to me a most romantic and dangerous profession.’

At Bignon’s we were given a private room and Oscar ordered a sumptuous meal with all the best wines, making substantial inroads into that one thousand francs. During dinner, he asked me about myself and my life and seemed genuinely interested in the most minute and mundane details of my existence. I noticed that, though he plied me with food, he ate sparingly, and there were times when he appeared to be in pain, yet he said nothing of it. He consumed a great deal of alcohol by which he seemed quite unaffected, as the elegant flow of his conversation was unstemmed.

It was when the meal was almost over that Oscar began to talk about himself. He was obviously reluctant to discuss certain incidents in his career—in his present state both his triumphs and tragedies must have been equally painful to recall—so he confined himself to observations about life, art and his approach to them both. With many of these I was familiar, and I waited for an opportunity to probe beneath this urbane, epigrammatic surface. I knew I must do so subtly, because he would immediately shield himself against any crude attempt to crack the carapace. However, a moment came when I saw my chance.

‘I am one of those people,’ Oscar was saying, ‘like Théophile Gautier, “

pour qui le monde visible existe

”. For whom the visible world exists. As for the invisible world . . . ah, that is a more troublesome issue! I acknowledge its existence, I admire its advantages, but I have no experience of its attractions. One reads Dante, of course, but his charm for me lies in the certainty that he is reporting inaccurately. His

Divine Comedy

is like the best journalism, full of the most fascinating gossip that one may choose to believe or disbelieve according to taste.’

‘But there must have been times,’ I said, ‘when you would have been tempted to pierce the veil and find out for yourself.’

There was a pause during which Oscar stared at me, then he drained his glass of burgundy and said quite casually:

‘Suicide, you mean? I was never really tempted to kill myself. Even when a part of me died in Reading Gaol, I never thought seriously of that as a way out. What I felt was that I must drain the chalice of my passion to the dregs.’

‘You have written that “each man kills the thing he loves”.’

‘My dear Ellwood, what on earth makes you think that I love myself? Self admiration and self love are quite different things. To love oneself is the beginning of folly, to admire oneself is the beginning of an exquisite career, and perhaps the end of it too. Besides, to commit suicide is not to kill oneself. On the contrary, it is to destroy everything but oneself. Don’t you see? We can escape all things but ourselves. That is man’s glory and his tragedy; at least it is mine, and that amounts to the same thing.’

‘But there must have been times, nevertheless . . . ?’

Another long pause followed, and I thought he was not going to rise to my challenge, but eventually he said: ‘You are quite right, and there was one occasion when I thought of ending my life. There is at Naples a garden where those who have determined to kill themselves go. It is called, I believe,

il Giardino dei Stranieri

, the Garden of Strangers. I do not know if the name has some sinister import or if it was called that long before it began to be put to such deadly use. Well, some two years ago, after Bosie had gone away, I was so cast down by the boredom of leaving the villa at Posilipo, and by the annoyance that some absurd friends in England were giving me, that I felt I could bear no more. Really, I came to wish that I was back in my prisoner’s cell picking oakum. I thought of suicide. Yes! Oscar Wilde, the passionate worshipper at the shrine of life, once contemplated such a thing.’

‘Did you go to this garden with the means of performing the act? What did you take with you? A gun? Prussic acid?’

‘Oh, my dear Ellwood, nothing so vulgarly practical.’ He laughed. ‘I suppose I had a vague notion that someone would be there to sell me the means, just as in pleasure gardens there may be sellers of balloons or ice cream. Incidentally, dear boy, talking of ice cream, they do a

Bombe

here which is a work of art. It is the

Mona Lisa

of ices. Shall we indulge, before our cognac?’

We ordered our ices and he continued.

‘It was too far to walk from my hotel in Naples so I determined to take a carriage. I tried any number of drivers, but they refused, even for ready money. They seemed to look upon the act of driving me to my grave as ill-omened. Eventually I secured the services of a villainous old fellow who was prepared to take me there in his dreadful old

carrozza

for a perfectly ridiculous sum of money.

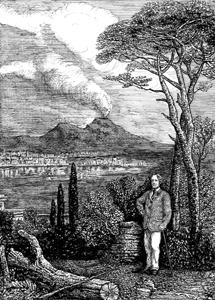

‘The Garden of Strangers is situated on a little hill overlooking the bay of Naples. I had occasion to reflect that the rather absurd injunction to “see Naples and die” had an ironic appropriateness for me. At any rate the view was, I suppose, as views go, a good one. Personally, I have very little time for views. Views are like women of a certain age: the vaster they are, the less they have to offer. Give me a simple silver-crowned olive tree to contemplate, or a dew drop upon a rose. It is the small things which enlarge the soul.

‘As for the garden itself, I understand that it had once been attached to the villa of a Neapolitan nobleman who, in a fit of misguided philanthropism, had left it upon his death to the Municipality. He had evidently disregarded the universal truth that what belongs to everyone, belongs to nobody; but perhaps his bequest was a subtle act of revenge on the world, for the Marchese di Catalani del Dongo—yes, that was his extravagant name—died by his own hand. It was the old story: unrequited hatred. He could not bear the fact that the friend whose wife he had so callously seduced was still very fond of him. Can you imagine a more cutting insult to an Italian lover? In England and France they do things differently, of course. In France they are realists and know that it is always the lover and not the cuckolded husband who is the true injured party, so they shrug their shoulders. In England respectability is everything: in private you threaten to horsewhip your wife’s lover; in public you take him out onto the golf course and offer him an insulting three stroke advantage. The Italians know nothing of golf: that is the secret of their charm, and the origin of their misfortunes.

‘Well the garden is not a very exciting affair. A few dusty paths wind between overgrown and uncared-for shrubberies. Tall sentinels of cypress—that most melancholy of trees—pierce the sky. There are a number of terraces where one may sit down upon a stone bench to contemplate the view, and, presumably, commit the awful act. So I went and sat down upon one of these.

‘It was a dull evening, thick and oppressive, and I knew that the coming night would be unblessed by stars. I was relieved to see that there was nobody about, nobody living, that is; but I immediately became aware that I was, nevertheless,

not alone

. I felt, as one sometimes feels when walking along a busy street in a great city, oppressed by the massed crowd of strangers whose lives are unknown to you, who pass by uncaring, who mean nothing to you and to whom you mean nothing. I thought then that the garden was well named.

‘Actual physical impressions were slight. I heard a rustling noise which might only have been the fluster of a bird in the shrubberies, and a sighing which could have been the breeze. Cloud-like things seemed to cluster round me, but that could merely have been the evening mist. But there was life there, of a sort, I was sure of it: the very stillness was like a live thing, and no bird sang.