The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler (6 page)

Read The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

‘ “They succeeded, but Maria had been put into such a state of shock by their clumsy violence that she resisted all my efforts to calm her. Perhaps I tried too hard to pacify her, but she was overwhelmed by it all. In short—I will not burden you with the details, signor—she perished in my arms. I had crushed the flower which I longed to nurture. Then, of all the outrageous acts of hypocrisy, those guttersnipes I had hired to capture the girl suddenly became full of remorse, and unknown to me, they went to the authorities.

‘ “The morning after Maria had died—I had spent a virtually sleepless night on her account—I woke to the sound of a hammering on my door. I looked out of my bedroom window to see the Carabinieri at the head of a rabble howling for my blood. Fortunately I was still fully dressed and I had a way of leaving my house secretly through a passage in my cellar which let me in to the next door house. I had not a moment to lose though, so seizing a loaded pistol from a drawer—I always kept one by me for such eventualities—I made for the cellar and the secret passage. Barely had I bolted the cellar door behind me when that stinking rout of rogues and Pharisees burst into my house.

‘ “In the event I was only a few minutes ahead of them. I knew by this time that there was only one means of escape, so I climbed the hill towards the Garden of Strangers. I heard their baying behind me and knew fear, but also a strange kind of exhilaration. At least my death would not be a slow descent into neglect and debility. I was past sixty, with all the ills that attend such an age, but for a while the chase put blood and fire into my old limbs. I gained the gate of the Garden with the rabble still a few hundred paces behind me.

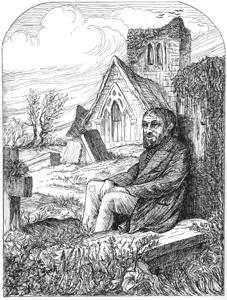

‘ “Even in death I won a victory. I cheated them. I reached this very bench with the mob hard on my heels. My old legs had begun to give way so that my pursuers had all but caught up with me. I showed them my gun, which held the cowards at bay, but my time had run out, and I prepared to die. I placed the muzzle of my pistol behind my left ear, slightly pointing upwards into the cranium. It was how an old Austrian General had once told me I should perform the act. That had been in my youth after the first of my disgraces, and I had repaid the General for his kind advice by using my pistol on him rather than myself. Then, as my persecutors closed in, I pulled the trigger. There was a momentary flash of agony, then I was dead and laughing at my persecutors with their shirt fronts and faces filthied by my blood and brains. So I remain, beyond them all, for ever.

‘ “I am not like the others here in this Garden of Strangers. I am one of the elect. I am not miserable like them; I am in ecstasy! I have an eternity to myself in which I can remember every twitch of pleasure, every gradation of the exquisite corruption of the flesh, every touch of my wrinkled finger on soft skin, every convulsion of pain, every scarlet scratch on the smooth white surface of youth, every hot tear that scalded the innocence of heaven. My soul still runs like fire through the lilies of God and scorches them with my everlasting lust!”

‘What else that monster shrieked in my ear—vile things that I will carry with me to my grave—I dare not repeat. I, Oscar Wilde—I, who thought he had plumbed the depths of sin!—could take no more of this. I knew that I must leave that garden at once; because, whereas my first two visitants had been sad creatures drifting through limbo, this last thing was a soul in Hell. I knew that I must escape him or risk eternal damnation.

‘The Count went on whispering his carnal litany in my ear as I tried to rise, but something physical was holding me there. I looked behind me and saw what looked like the black web of a great spider which had been woven onto the back of my coat, binding me to the seat of the bench. I tried to detach myself from it but my hand became ensnared. It stuck to me, this black and viscous horror.

‘Ah, you will say, it was merely pitch or black paint which I had inadvertently sat down upon. You Americans are irreconcilably prosaic, but that is because you are young. Youth is the oldest tradition of your nation, and the young are always prosaic. The young believe that poetry is only a beautiful way of telling lies; whereas the old know it to be the sole medium of bitter truth. Where was I?’

‘Still in the Garden of Strangers.’

‘Ah, yes. Well, I believe that I might have been caught forever in that dreadful web, but just then the sun broke from behind the hills overlooking the bay of Naples, and it was at last a new day. With the dawn all my spirits fled from me, their mist burned up by the sun’s morning rays. So I wrenched my coat off the seat, quitted the Garden of Strangers and never returned. My coat was ruined which saddened me because we had become attached to one another. After all, I owed my tailor a great deal of money for it.’

He broke off wistfully and stared into space for a moment. ‘The really precious things in life are those for which one cannot pay. Would you care for another brandy, or does your soul revolt against such excess?’

I shook my head.

‘I should not have asked. One should never try to lead others astray: it is the one unpardonable sin and a privilege one must reserve for one’s self. I was once very nearly tempted into playing a game of football. Fortunately I was able to plead successfully that I had a feverish intellect, so they let me off. But had I succumbed, only think what dreadful consequences would have ensued. I might have become respectable.’

‘What is so wrong with that?’ I asked, hoping, I guess, to provoke him once more, but I got more than I bargained for.

‘My dear Ellwood,’ said Oscar, now without a trace of melancholy or languor in his voice, ‘respectability is the only crime because it is the betrayal of the self. Respectability is the taking up of moral attitudes and the denial of morality. It condemns the sinner in public, but in secret condones the sin. How could I, its most notorious victim, defend respectability? It prefers the simple lie to the bewildering truth. It is the comfort of cruel men, the ice on the mirror, the cloak that hides the dagger. It was the crucifier of Christ; it is the suicide of the soul. If I had murdered myself that day in the Garden of Strangers I would have become respectable because, in the eyes of my fellow countrymen, I would have “done the decent thing”. And there is no more indecent act in this world than to do the decent thing for the sake of respectability.’

When Oscar had finished there was a silence while the fire slowly departed from his eyes. He sighed as if suddenly exhausted by his own conversation; then summoned the waiter to order another cognac for himself. I asked him if, since his adventures in the Garden of Strangers, he had ever been tempted again to take his own life.

‘No. I was cured of that. You see, I knew that all three of those shades had killed themselves in vain. And when I thought that such would be the fate of my soul too, the temptation to kill myself left me and has not come back.’

‘And after all, how could you have imagined spending all your after-life in Naples?’ I said.

Oscar laughed: ‘No, the cooking is really too bad. At least I shall be dying in Paris where the cuisine approaches that which one can expect from the after-life at its best. When one is about to feast with the dead, it is as well to know what is on the menu.’

‘And who pays for that particular feast?’ I asked, as the waiter entered the room. Oscar settled the bill with an extravagant tip. As he struggled to rise from the table, he grimaced with pain, so I helped him to his feet. He acknowledged my assistance with a smile and a movement of the hand that was like the blessing of a dying pontiff.

‘My dear Ellwood,’ said Oscar, ‘a gentleman knows but never tells.’ Absently he patted the waistcoat pocket in which reposed the sad remnants of my one thousand francs.

AMONG THE TOMBS

‘I don’t think the Church of England will ever take kindly to the idea of sainthood,’ said the Archdeacon. ‘No. It won’t do. It’s not in our nature.’ The Archdeacon is one of those people who has decided views about absolutely everything, a useful if exhausting quality.

It was the first night of our annual Diocesan Clergy Retreat at St Catherine’s House. Most of the participants had gone to bed early after supper and Compline, but a few of us had accepted Canon Carey’s kind offer of a glass of malt whisky in the library. It was a cold November evening and a fire had been lit. Low lighting, drawn damask curtains, and a room whose walls were lined from floor to ceiling with faded theology and devotion contributed to an intense, subdued atmosphere.

I suppose whenever fellow professionals get together there will tend to be a mood of conspiracy and competition, and clerics are no exception to the rule. Serious topics are proposed so that individuals can demonstrate their prowess and allegiances. The Archdeacon, in any case, does not do small talk.

‘But there are people in our tradition whom we do revere as saints,’ said Bob Mercer, the Vicar of Stickley.

‘Name them!’ said the Archdeacon belligerently.

‘George Herbert, Edward King of Lincoln. . . . What about the martyrs Latimer and Ridley? And Tyndale?’

‘Yes, yes. But these are figures from the past. Anyway, ask the average man or woman in the pew what they know about Edward King. I mean that we have no living and popular tradition, no equivalent to Mother Teresa or Padre Pio.’

‘What about Meriel Deane who started the Philippians?’ said Canon Carey.

A young curate who had just crept in confessed he had never heard of Meriel Deane. I would have said so myself had I been less timid about showing my ignorance. Rather condescendingly the Archdeacon enlightened us. Meriel Deane, he said, had founded the Philippian Movement to help the rehabilitation of long term, recidivist prisoners who had just left gaol. They could spend their first six months of freedom at a Philippian House, usually in a remote country spot, supervised by one or two wardens. The regime pursued there was at once austere and easy-going. Inmates could come and go as they liked, and had no work to do apart from minor household chores, but there were regular meals and periods of silence and meditation. People were given space to reflect on their lives. The charity was named after the town of Philippi where St Paul had been imprisoned. The Philippians were still in existence and doing good work though their founder was now dead.

The Archdeacon concluded his lecture by saying ‘I met Meriel Deane on several occasions. The woman was nuts. No doubt a good person in her way, but completely off her head, so not in my view a candidate for sanctification.’

‘Oh, yes, she was rather disturbed at the end, but she wasn’t always like that,’ said a voice none of us recognised.

The speaker was an elderly priest whom I noticed had been placidly silent all through supper. He wore a cassock rather like a soutane which put him on the Anglo-Catholic wing of the church, an impression which was confirmed when I heard him being addressed as ‘Father Humphreys’. He must have been past retiring age, a small, stooped man with a wrinkled head, like a not very prepossessing walnut; but, as he spoke, his face gradually assumed character, even a certain charm.

‘So you knew her, Father?’

‘Very well, for a time. One of her first ‘Philippian’ houses was in my parish, Saxford in Norfolk.’

‘And she wasn’t potty?’

‘She was not potty

then

.’

‘So when and how did she go potty?’ asked the Curate. The Archdeacon was frowning. He obviously felt that repeated use of the word ‘potty’ was lowering the tone.

‘Well,’ said Father Humphreys, who had sensed the Archdeacon’s unease and seemed amused by it. ‘That’s not the adjective I would use, but something definitely went wrong. As things do. One wonders why, but there is no real answer. Not this side of the grave at any rate.’ The last sentence was spoken faintly, as if he had forgotten the presence of others and was talking to himself.

‘Do you know what exactly “went wrong”, as you put it?’ asked Canon Carey.

‘No. Not exactly. But I’ll tell you what I know if you like. It would be quite a relief. I’ve never told anyone before, and it might be good to unbosom.’

The rest of us began to settle into armchairs and sofas. A bedtime story! What a treat! That word ‘unbosom’ had marked him out in my mind as an unusual and interesting person. And yet—and I don’t think this is merely hindsight—I am sure I felt uneasy, even a little fearful about what Father Humphreys was going to reveal. Despite offers of a more comfortable seat he established himself on a low footstool in front of the fire. In that pose, crouched with his knees almost up to his chin, there was something in his appearance which made one think of a little old goblin out of a book of fairy tales. As he spoke he barely looked at us, but addressed most of his story to the pattern on the threadbare rug at his feet.

**

Was Meriel Deane a saint? She had saintly qualities certainly, but I tend to think that true saints are less self-conscious about their sanctity, and less disposed to remind you of it. Let us just say that in her eccentric way Meriel was on the side of the angels and leave it at that.

I had been the Rector of Saxford for about five years when she came to our village and I remember clearly the first time I met her. One’s first and last images of a person are often the most vivid. With Meriel, it was the same one: the back of her head. Which was appropriate, I suppose, because she was as distinctive in appearance from the back as from the front.

Every morning I would open the church at seven, say prayers and then go to the Rectory for breakfast. In those days—I am talking about 1964—we were less careful about keeping the church under lock and key. I don’t know whether any of you know St Winifred’s, Saxford? Not very special, but some nice Norman corbels in the porch and a painted rood screen which somehow managed to survive both the Reformation and Cromwell’s iconoclasts. One of the panels has a rather lively depiction of St George and the Dragon on it.

I mention that because one morning in March 1964 when I returned to the church after breakfast I found it to be occupied. A woman was kneeling, very upright, in one of the front pews, directly opposite that painting of St George and the Dragon. She did not move an inch as I entered. She was wearing a coat and skirt of some loosely knit woollen fabric, rather indeterminate in colour, but it was her head which attracted my attention. It was small and neatly shaped; her iron grey hair, obviously long, had been coiled up into an elaborate bun on the back of her head. It reminded me of a sleeping snake.

I don’t know what you think is the correct etiquette when you find someone praying in your own church. I tend to sit down quietly in a pew and wait for them to finish. I read a prayer book and tried not to look at her too much, but she did rather fascinate me. She was formidably motionless: evidence of a disciplined, perhaps rather rigid, piety.

After about five minutes she got up, turned round and smiled directly at me.

‘You must be Father Humphreys, the Rector,’ she said. ‘I am most frightfully sorry. I should have come to introduce myself before, but we’ve just moved in to the Old Tannery in the village and chaos has been reigning supreme. This is positively the first instant I’ve had to myself. I’m Meriel Deane.’ She came forward and shook me firmly by the hand.

I rather liked her. I suppose she must have been in her late fifties. She had a handsome, apple cheeked, sexless face and strangely bright eyes. Her body was tall, spare and without shape; she moved in long, determined strides. She seemed completely unselfconscious, oblivious of the effect she was having on people, like a schoolgirl before her first erotic awakening, but not at all gauche or ungainly. Her voice was an upper class, intellectual bleat, like a Girton professor, easily parodied and in itself unattractive, but not offensive in her because she spoke without affectation.

I had vaguely heard of Meriel Deane and the Philippians, but she filled me in on her work. The Old Tannery was her third Philippian House, and she was going to stay to run the place herself for at least a year. By the end of our first meeting I had offered to take Compline for them at the Old Tannery on Friday evenings and had given her a spare key to the church so that she could go in any time she liked and, as she put it, ‘have a little pray’.

I was soon a regular visitor at the Old Tannery. It was a pleasant atmosphere. The furnishing was rather Spartan—very few easy chairs, rush mats on the floors—but it was always warm and clean.

You might think that the village would have objected to an invasion by this strange woman and her gang of ex-convicts but reaction was very muted. The men who stayed with her were all middle-aged to elderly. One would occasionally see them lumbering about the village, usually in small groups of twos and threes, rarely alone. They bought sweets and tobacco at the local post-office-cum-general-store, but otherwise kept themselves to themselves. They did not go into the pub, having been forbidden it by one of Meriel’s few House Rules. Otherwise, they had little impact on the community.

I do not remember Meriel’s men as individuals. In my memory they all seem to merge into a single generalised portrait. They were big people with simple, troubled faces, and plain, monosyllabic names like Bill and John and Pete. Meriel behaved towards them like a kindly schoolmistress in charge of a class of not particularly bright infants, a treatment to which they responded surprisingly well.

‘They are Life’s Walking Wounded,’ Meriel used to say to me. There was something about that phrase, or perhaps the way she said it, that I did not particularly like. It was just a little smug, I thought. That was the one aspect of her which I found mildly objectionable. She could appear rather pleased with herself; but then she had good reason to be.

I say that all these Johns and Bills and Petes were indistinguishable in my mind, but there was one very notable exception. This was a man whom I shall call Harry Mason, and he was distinctive in every way.

He arrived in the summer of that first year, round about July when the air was heavy and hot and green with growth. I noticed him at once because he was one of the few men who always walked alone around our village.

He was maybe a fraction younger than the average run of Meriel’s inmates, early forties I should say. He was of average height, but thin with spindly arms and legs. He had a very prominent lower jaw and lip, a near deformity which made him look as if he were permanently and joylessly grinning. This Hapsburg trait, combined with a neat moustache and beard, gave him a striking resemblance to the Emperor Charles V, as portrayed by Titian. Had he cultivated the likeness? It is possible, because, unlike the others at the Old Tannery, he was clearly an educated man.

I never knew what he had been ‘in for’; I never asked and I doubt if Meriel knew herself. She had a habit of acting as if her charges had no past and that only the present mattered.

One Friday evening soon after he had arrived I conducted Compline as usual at the Old Tannery. These occasions were not in any way solemn or pompous. We all gathered in the main room and seated ourselves in a rough circle. There was no kneeling or anything like that. The men would often follow the service with a prayer book in one hand and a mug of tea in the other, sometimes slurping it noisily during the pauses. But nobody minded and there was a good deal of chatter and laughter when it was all over. Compline is in any case the most simple and beautiful of services.

The Gospel reading for that evening was from Mark Chapter 5: the possessed man called Legion who dwelt among the tombs and whose Devils Jesus cast out into the Gadarene Swine. It had been in the lectionary for that day, but I remember wishing I had taken thought before and chosen a rather less sinister passage. Meriel read it for us in her clear, high bleat, and it was heard in an unusually intense silence. The customary shuffles and sippings of tea for once were banished.

After it was over normality returned. I was pressed to stay for cocoa and a ginger biscuit, and there was general chat of a not very interesting kind. Meriel was trying to recruit some of the men to go with her in a week’s time to an organ recital at a neighbouring church. There were few takers, and she was being mildly teased about her enthusiasm for such things. While this was going on I had an opportunity to observe Harry Mason, the new resident to whom Meriel had briefly introduced me before the service.

He was standing by the window, apart from the others, looking on but not participating. I saw one of the other men pass him carrying a tray laden with mugs of cocoa. It seemed to me that the man made studious efforts to keep as far from Mason as he could. When it was Mason’s turn to be provided with a cup of cocoa the man did not hand it to him directly but put it on an adjacent table where Mason could pick it up.

Mason noticed that I had observed his tiny humiliation. He picked up his mug and saluted me with it before drinking. I returned the compliment.