The Cost of Courage (7 page)

Read The Cost of Courage Online

Authors: Charles Kaiser

André’s last sentiment did not turn out to be prescient.

His father’s response has not survived. But ten weeks after writing his letter, André has returned to France to resume the struggle against the Germans.

*

This led, of course, to Churchill’s famous riposte eighteen months later: “Some chicken. Some neck!”

†

Later, de Gaulle said of France’s collapse in 1940, “We staggered, it is true. But was this not, first of all, a result of all the blood we had shed twenty years before in others’ defense as much as our own?” (

Complete Wartime Memoirs

, p. 461).

‡

De Gaulle spoke on June 18, but Christiane thinks she didn’t hear the broadcast until it was repeated the following evening.

§

At the height of his fame, Lindbergh became one of Hitler’s most naïve supporters.

The Resistance was irresistible.

— André Postel-Vinay

T

HE FEARS

Jacques Boulloche described in his letters of a permanent separation from his family were premature. At the end of the summer of 1940, his wife and daughters return to the French capital from Brittany, and they move back into the family’s spacious apartment.

Jacques’s youngest daughter, Christiane, has a visceral reaction to what she sees in the newly occupied capital. The French

tricolore

has been banned. In its place there are huge swastikas swaying in the wind, freshly painted street signs in German — “black on yellow,” she remembers clearly — and German drummer boys in front of Wehrmacht soldiers goose-stepping down the Champs-Élysées. “There would be parades in the morning and they would sing. And they sang well — that was especially annoying!”

Christiane is stunned by all of this. She sees it as “the visible proof of our defeat. Seeing the Germans in Paris is ghastly. You feel like you are no longer at home. We were touching the reality of the Occupation with our fingers. It was a succession of shocks.”

A German soldier complained to an attractive Parisian girl that her city seemed sad. “You should have been here before you got here,” she replied.

This is when Christiane begins to ride a bicycle, when there is no longer any heat in her parents’ apartment, and when she begins to feel hungry all the time. Jacqueline goes to work for an organization that sends packages to French soldiers who are imprisoned in Germany.

Jacques and Hélène Boulloche share their children’s revulsion at the German Occupation. As early as July 1940, Jacques writes to his wife that the new anti-Semitic campaign is going to make life difficult for one of his colleagues. Three months later, the government publishes its first “Jewish law,” which excludes Jews from the higher levels of public service, as well as professions like teaching and the press, where they might influence public opinion.

Back at her Paris lycée in the fall of 1940, Christiane and her friends take up a collection for Mademoiselle Klotz, a much-loved history teacher, who is fired after the publication of the new law. Christiane is shocked by the persecution of the Jews, especially when one of her classmates, Janine Grumbach, is forced to start wearing a yellow star.

Beginning in October 1940, all foreign Jews can be interned at the discretion of prefects. On November 1, even in the unoccupied zone, every Jewish-owned business must display a yellow poster in the window:

ENTREPRISE JUIVE

.

By the start of 1941, some forty thousand Jews are held in seven main camps, in atrocious conditions. Some three thousand Jews perish in the French camps even before the Final Solution has begun.

In June 1942, every Jew over the age of six in the occupied zone is ordered to wear a star over the heart, and they are forced to buy three of them from their local gendarmerie. Adding insult to humiliation, those purchases are even deducted from their clothing coupons. In July, they are banned from all public places: cinemas, main roads, libraries, parks, cafés, restaurants, swimming pools, and phone booths, and they can only ride in the last car of the Métro.

By 1941 the swastika was everywhere in Paris. Here the former (British) WHSmith had become a German bookstore on the rue de Rivoli.(

photo credit 1.8

)

Christiane considers all of this outrageous, and she thinks that her parents are helping some of their Jewish friends to escape. Her family is also directly affected by the new law, because one of her cousins, a surgeon named Funck-Brentano, has a Jewish wife, and she is forced to go into hiding.

*

IN SPITE OF

their shared hatred of the Boches, the two halves of the Boulloche family choose very different paths after the fall of France. Unlike their three youngest children, neither Jacques nor Hélène will ever join the Resistance.

Jacques and Hélène both turn fifty-two in 1940, and they share the caution of middle age. Jacques helps some Jewish friends to go into hiding, but he is always discreet. He is also careful not to do anything that might jeopardize his family’s safety, or weaken the nation, to which he and his ancestors have devoted decades of service.

As the British historian Julian Jackson observed, “Conduct which might be described as collaboration could incorporate a myriad of motives including self-protection, the protection of others, even patriotism.”

Christiane doesn’t consider her father “pro-German at all.” She thinks he merely wants to make France work for the French, “not for the Germans.” The Boulloches defiantly listen to the BBC at home. They realize that if the British don’t stay in the fight against Hitler, their only hope for the future will be extinguished.

Jacques Boulloche never confronts the German occupiers directly. He keeps his government job, and he commutes to Vichy, the seat of the collaborationist government. His family notices he is always particularly depressed when he returns from Vichy. He never tells his children whether he has signed an oath of loyalty to the Vichy government, but he is almost certainly required to do so.

Jacques and Hélène’s oldest son, Robert, serves in the army during the German invasion, but he avoids capture after the armistice. Now he has returned to his job as an inspector for the Finance Ministry, in Toulouse.

Robert shares his parents’ prudence and their commitment to the French government. Like his father, Robert probably sees some value in keeping France functioning for the French, despite the invasion of the Germans.

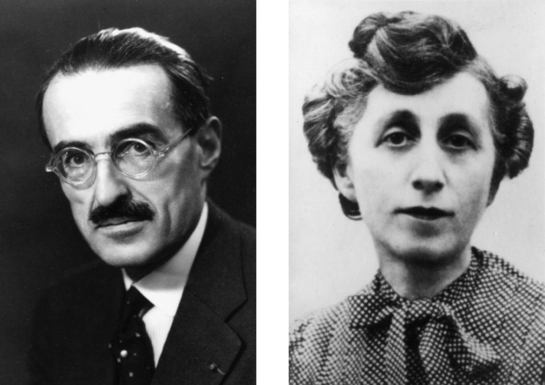

Jacques and Hélène Boulloche. Jacques was the family patriarch, who kept his job as the director of the national bureau of highways after the Occupation began. Like her husband, Hélène never joined the Resistance. But when her daughters told her that they had, she said, “That’s what I would have done.”(

photo credit 1.9

)

A twenty-seven-year-old bachelor, Robert is not as good-looking as his younger brother, André. But he has a terrific sense of humor, a passion for art, and an impressive collection of original paintings.

At the end of 1940, Robert becomes the first member of his family to be asked to join the Resistance. The invitation comes from André Postel-Vinay, who had met Robert two years earlier, when the two of them took the exam to become finance inspectors together.

Postel-Vinay is a strikingly handsome twenty-nine-year-old, with delicate features set off by a broad forehead and an aquiline nose. As a lieutenant in the 70th Régiment d’Artillerie in 1940, he is celebrated for his bravery and his exceptionally accurate shooting. On June 17, he is captured by the enemy, but he manages to escape a week later. After three days on foot, he makes it back to his parents’ home in Paris, utterly exhausted.

Robert Boulloche was the oldest son in the family, and shared some of his parents’ caution. He declined André Postel-Vinay’s invitation to join the Resistance at the end of 1940 — but he predicted that his younger brother would be eager to join the fight against the Germans.(

photo credit 1.10

)

The apartment is empty, because his parents are in Brittany. The next morning, he is awakened by a German military ceremony taking place in the street below. When he goes to the window, he has the same reaction as Christiane and thousands of others. He is appalled by the savage sight of German soldiers holding gilded crosses in the air as they parade down the street.

LIKE JACQUES BOULLOCHE

, Postel-Vinay had seen the war coming many years earlier. After the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, when Hitler ordered the execution of Ernst Röhm, the gay commander of the Nazi SA, two army generals, and at least a hundred others, Postel-Vinay decided that “war is the only way

to communicate with the Nazis — because even among themselves, they behave like butchers.”

(In a speech to the Reichstag after the bloody massacre, Hitler freely admitted that what he had done was completely illegal. The legislature quickly passed a law that retroactively legalized his butchery.)

After France’s collapse in 1940, Postel-Vinay thinks that any victory over the Nazis will take a very long time, if it ever comes at all. But he is propelled by the conviction he shares with the small number of very early

Résistants

: He believes that his life will have no meaning until he finds a way to fight for the Germans’ defeat.

By October 1940, he has linked up with one of the earliest British Resistance groups in the Paris region, which is helping downed British airmen escape back to England through Spain. Then he connects with a group of French officers from the army’s intelligence service, the Deuxième Bureau, who are collecting information on German troop movements and relaying it to London.

Postel-Vinay also makes contact with a group of anti-Fascist intellectuals at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, who have begun to organize in the summer of 1940. Most of them are leftists, and some of them aren’t French, including the group’s most active member, Boris Vildé, a linguist with anarchist leanings and Estonian origins.

The group at the Musée de l’Homme is one of the very first Resistance groups. In December 1940 it starts to publish the newspaper called

Résistance.

During the next three years, dozens of other clandestine newspapers will appear all over France. Delivering some of these publications is one of Christiane Boulloche’s earliest acts of resistance.

When Postel-Vinay asks Robert, his former classmate, if he will join the Resistance to collect intelligence about the Germans for the British, Robert shows no interest. He doesn’t seem to think the work will be very useful, and as the oldest son in his family, he probably shares some of his parents’ caution.