The Cost of Courage (5 page)

Read The Cost of Courage Online

Authors: Charles Kaiser

The prediction is nearly correct. By the end of the month, Germany has conquered Poland, and Hitler divides up the country with Stalin. Organized Polish resistance is over by the first week in October.

*

The British diplomat and politician Duff Cooper, who quotes this passage in his autobiography, points out that by this time “anybody who read the newspapers” was already aware “not only of the hideous persecution of the Jews which [Hitler] had initiated, but also of the blood-bath of June 1934 [Night of the Long Knives] in which he had slaughtered without trial so many of his own closest associates.” (

Old Men Forget,

p. 197)

†

At the end of World War I, Canadian general Andrew McNaughton said of the Germans, “We have them on the run. That means we will have to do it over again in another 25 years.” Or, as satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer put it in 1965, “We taught them a lesson in 1918 — and they’ve hardly bothered us since then.”

Throughout the ’30’s, France and Britain had been slow, often indecisive and hopelessly outmaneuvered by Hitler’s devilish strokes. The ponderous bourgeois gentlemen in heavy suits and hats who led the Western democracies didn’t have a chance against the cunning gangster.

— Stanley Hoffmann

T

HE CONCLUSION

of the German campaign in Poland in the fall of 1939 marks the beginning of the Phony War. This period of relative calm will last seven months on most of the European continent. Churchill calls it the Twilight War. In France it is

drôle de guerre

(funny or strange war); in Germany,

Sitzkrieg

(sitting war — a pun on

Blitzkrieg.

)

While Russia invades Finland at the end of November, and Germany and Britain engage in occasional skirmishes at sea, French and German troops remain mostly silent, as they gape “at each other from behind their rising fortifications” on France’s eastern front, throughout the winter of 1939.

After her father moves his wife and daughters out of Paris in the fall of 1939, Christiane Boulloche embraces her new life at the lycée in Fontainebleau. Her classes are smaller than they were in the capital, and she excels with very little effort. Her parents agree to board a French officer who teaches at the artillery school

in Fontainebleau, and his twenty-something students are frequent guests at the Boulloche dinner table — a beguiling circumstance for a fifteen-year-old girl.

At the end of 1939, most French officers still believe in France’s military superiority, and that is the opinion Christiane hears at her dinner table. Like most French people (except de Gaulle), the Boulloches still hope that they will be protected by the Maginot Line, the massive fortifications France has built above- and belowground along the German border between 1929 and 1940. They also think that when the war finally comes to France, it will be a short one.

Christiane enjoys the period before Germany invades France. It feels like a “new and exciting adventure.” But she is jealous of her brothers, because they are actually able to

do something,

by being in the army. Predictably, her brother André is dissatisfied with his calm life as a lieutenant with the 6th

régiment du génie

(engineers) on the eastern front. Starving for action, he snares a transfer to the aviation officers’ school in Dinard.

As the Phony War continues through the winter, more and more children are evacuated from the northeast corner of France in anticipation of the expected invasion. While their parents stay behind to work, the children are relocated to places like the golf club in Fontainebleau. The children’s presence, and a nightly blackout, are the only things Christiane experiences that make the possibility of an actual war seem real. Jacqueline, who has recently graduated from Sciences Po (the institute of Political Science in Paris), spends her days working with the refugee children from the north.

The eight-month-long lull between the time Britain and France declare war on Germany and the moment when full-scale hostilities begin does not work to the Allies’ advantage. After Hitler and Stalin announce their nonaggression pact in August 1939, the French Communists take their cue from Moscow and end their active

opposition to the Nazis. They denounce the war as “an imperialist and capitalist crime against democracy.”

Meanwhile, morale plunges among French troops, who are undermined by shortages of socks and blankets, as well as simple inaction. Even the weather conspires against the French: The winter of 1939–1940 is the coldest France has shivered through since 1893.

In November 1939, Jean-Paul Sartre writes in his diary that the men who were mobilized with him were “raring to go at the outset,” but three months later they are “dying of boredom.”

WHEN THE GERMANS

finally storm into Holland and Belgium on May 10, 1940, the impact is felt almost instantly in Fontainebleau. Christiane experiences the effects of the crushing advance of the enemy, as thousands flee in front of the German blitzkrieg, traveling in horse-drawn carriages and cars overflowing with exhausted women and children.

No one has expected the Germans to roll over the French Army so quickly, not even Germany’s own generals. In England, Neville Chamberlain resigns as prime minister, as his dream of “peace for our time” evaporates, and the king summons Winston Churchill to Buckingham Palace to form a new government to fight the war.

Churchill is appalled by the speed of the German onslaught. The new prime minister learns that German tanks are advancing at least thirty miles a day through the French countryside, passing through “scores of towns and hundreds of villages without the slightest opposition, their officers looking out of the open cupolas and waving jauntily to the inhabitants. Eyewitnesses [speak] of crowds of French prisoners marching along with them, many still carrying their rifles, which were from time to time collected and broken under the tanks … The whole German movement was

proceeding along the main roads, which at no point seemed to be blocked.”

With hundreds of thousands of refugees now surging southward, Jacques Boulloche once again tries to move his wife and daughters out of danger. This time he sends them to an aunt’s house in Perros-Guirec, in Brittany, in the northwest corner of France, far from the Germans’ invasion route. Christiane is miserable because she has a new puppy that she isn’t allowed to bring with her, and she never sees that dog again.

But when the three Boulloche women flee Fontainebleau at the end of May, they are much more fortunate than the refugees who had been housed at the golf club. The cars carrying those children are bombarded from the air, and scores of them are killed.

As France’s army is being pulverized at the end of May, a gigantic crowd gathers in front of Sacré-Coeur on the hill above Paris to pray for victory. At the end of the emergency service, fifty thousand voices belt out “The Marseillaise.” More than six million French citizens have already abandoned their homes.

Across the channel in London, a thirty-year-old foreign correspondent named James Reston writes in the

New York Times

that a German invasion of the British Isles is now considered nearly certain.

*

Looking down from a plane, the writer-pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry observes that the mobs of refugees below look like a massive anthill, kicked by a giant.

ON JUNE

3, more than one hundred German bombers attack Paris. The French authorities claim they have shot down twenty-five of the planes, but the bombardment kills more than 250 Parisians and wounds 600 more.

“This is what we dreaded for so long, and what we hoped might never happen,” the

New York Times

declares on its editorial page the next day.

It seems worse, somehow, than any of the other crimes perpetrated by Germany in this war … Great cities … are more than aggregations of men, women and children. They are the treasure-houses of the Western spirit. Whoever strikes at them strikes at all that man has built through ages of sacrifice and suffering …

Free men will not endure these things without a new resolve to destroy the forces of evil that have sent the German bombers on their errand. The great columns of smoke and flame that rose above Paris yesterday … were also the first fires of a wrath such as our world has never known. If this kind of fiendishness continues, if Paris and London are to become shambles of ruined buildings and murdered civilians, the fires of hate will not be quenched in our time. The anger of civilized peoples will burn so fiercely that it will consume the hateful German system which has loosed these horrors upon the world.

The

Times

is almost alone in its prescience. Certainly no one in France is optimistic about the eventual defeat of the Nazis the day after the bombardment of Paris.

SIX DAYS LATER

, the French government prepares to evacuate Paris. Jacques Boulloche, the director of the national bureau of highways, is ordered to leave the capital for Royan, three hundred miles to the south on the western coast of France. That evening he heads for his country house in Fontainebleau, but his car breaks down on the way, and he doesn’t get there until four o’clock in the morning.

The next day he opens his fountain pen to write a letter to his wife:

The Boulloche country house in Fontainebleau, where Jacques Boulloche retreated as the Germans advanced on Paris in 1940.(

photo credit 1.5

)

I can’t describe my feelings when I got here, considering all that we’ve had to abandon. And yet, we are among the lucky ones … The peace of the garden and the fragrant smells make the unfolding tragedy seem like nothing more than a bad dream …

The same day as Jacques writes to his wife, Norway surrenders to the Nazis, and Italy declares war on Britain and France.

The capital Jacques has left behind is filled with smoke from burning archives and incendiary bombs. On June 10, the French government declares Paris an open city, meaning it will no longer be defended — after the Germans are already inside the city’s gates. There are twenty thousand people jammed outside the doors of Gare d’Austerlitz, trying to force themselves onto trains leaving the capital.

The

New York Times

reports on June 13, “The German guns are battering at the hearts and minds of all of us who think of Paris when we try to define what we mean by civilization … Of all cities it expresses best the aspiration of the human spirit.”

Paris falls the next day, on June 14. By then, its population of three million has shrunk to eight hundred thousand.

Jacques Boulloche is distraught. His boys are at the front, and his wife and daughters are hundreds of miles away in Brittany. He is terrified that he may never see any of them again. He and his wife have an exceptionally strong bond. They are so close, their children sometimes complain that it’s hard to find any room for themselves in between them.

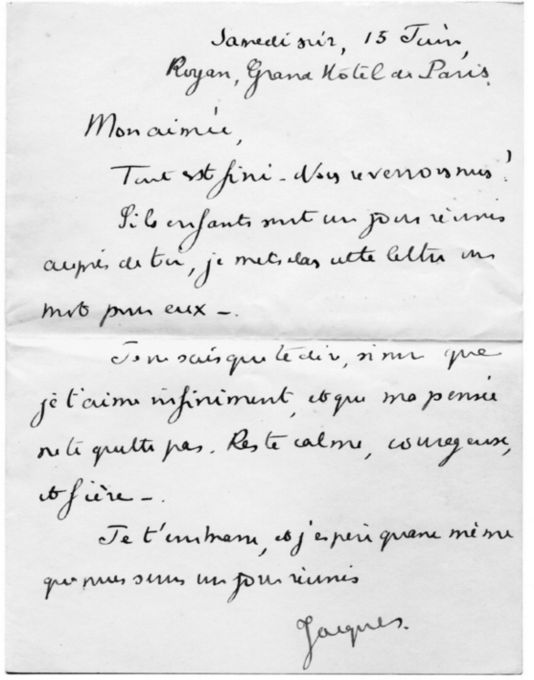

On the afternoon of June 15, Jacques sits down at the desk in his room at the Grand Hôtel de Paris in Royan to write another anguished letter to his wife:

My Beloved,

Everything is finished. Will we ever see each other again?

In case you are reunited someday with the children, I have included a message for them in this letter.

I don’t know what to say, except that I adore you, and I can’t stop thinking about you. Stay calm, courageous and proud.

I love you, and I still hope that someday we will be reunited.

Jacques

And this is what he writes to his children:

If I never see you again, know that my last thoughts will have been about the four of you.

I hope you will once again see a free and joyous France.

I love you with all my heart.

Your Father

Jacques

In a letter to his family, Jacques Boulloche pours out his fears about what the German invasion will bring.(

photo credit 1.6

)

*

In the underground bedroom Churchill slept in during much of the war, his bed faced a map that highlighted all the possible invasion points of the British Isles.