The Delaware Canal (16 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

The carpenter boats were used to transport workersâsometimes as many as fifteen menâwho would repair locks, bridges, company-owned houses and stables. Repairing a leak in the canal during operating months was complicated. The carpenters would build a “dam” around the spot, leaving enough room for a boat to pass, and pump the water out before using whatever materials would work to fill the creviceârocks, straw, leavesâand then the area would be covered with clay. Once the clay hardened, the dam was removed and the water would cover the repaired area while they all kept their fingers crossed that the repair worked.

The men on the flicker boats kept the banks clean. They cut away weeds, bushes and tree branches that could choke the canal and hinder movement of the boats. The flicker operators also filled in holes along the towpath to prevent mules and drivers from breaking an ankle.

“Bank bosses” were responsible for their own sections of the canal, blacksmiths took care of shoes for the mules and repaired tools and objects made of metal used on the boats or at the locks and watchmen took care of the waste gates during heavy storms. All had their part to play, and all contributed to the success of the canal.

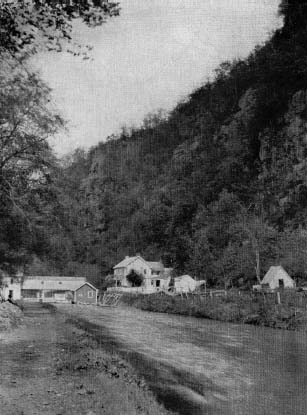

The cliffs at the Palisades in the “Narrows” rise abruptly along the river to three hundred feet, leaving very little room for the towpath and canal, but they contribute to the breathtaking scenery along the canal.

Courtesy of Historic Langhorne Association

.

When the Captains Were Kings

The boatmen made the transport of coal, iron ore, lumber and stone appear easy. But appearances aren't always what they seem, for each trip was at once backbreaking, dreary, dangerous and tedious. If the inventive geniuses of the newly formed nation were the brains of the American Industrial Revolution, it was the hardworking populace of America who were the backbone and muscleâthe miners who dug out the coal, the carpenters who built and maintained the structures and boats, the firemen who worked the furnaces, the men who gripped the shovels to dig the channels and the laborers who laid the rails.

And during the rise of the “navigation revolution,” it was the boat captains who were the kings of the narrow waterways. Their productive efforts during long, tiring days must be recognized as the valuable contribution it was to the economic growth of the country. Without the efficient and safe transportation of coal and other natural resources to the major cities of the East, the Industrial Revolution would have been much slower to evolve.

Each canalboat trip would begin when the boat captain pulled his boat up under the coal chutes at Mauch Chunk. Once his boat was loaded, he would move on to the weigh lock, get his paperwork from the lock tender there and then either continue on to Easton or wait until morning. Canaller Henry Darling said:

We'd tie up at one of the locks for the night. Then get an early start in the morning and be in Easton by 3 p.m., spend the night there, and be in Bristol by noon on the fourth day

.

63

That was if everything went as expected along the wayâno freshets (floods), no mishaps with the mules, no leaks in the canal, no problems at the locks, no holes in the boat.

They would begin their 106-mile trip that day, and when the canal season was over, if they were able to maintain a regular schedule, they would travel a distance of approximately 3,000 miles in that one seasonânormally lasting 212 days, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on the weather.

Once in Bristol, if the tide was right, they would unhitch the mules, leave them stabled in Bristol and shove out into the Delaware River, where the tugs would pick them up and tow them to Philadelphia. If they worked for the company, they stayed in Bristol, were given another boat and started back up the canal, and if that was the case, the boatmen didn't always get a boat of equal quality to the one they had just surrendered. Sometimes the cabins would be infested with bedbugs; sometimes there was less room in the cabin or stoves didn't work as well as they had on the last boat.

Captain Pearl R. Nye, who had been born on a canalboat and was the fifteenth of eighteen children of an Erie Canalboat captain and his wife, spent much of his life collecting folk songs written about or by canal men. These songs, recorded between 1937 and 1938, are now located in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. They uniquely describe and preserve the life of the nineteenth-century canal families. From one of those songs, “The Old Skipper,” we get a glimpse of how they felt about their work.

There's tanbark and hoop poles, wet goods, merchandise,

Clay, coal, brick and lumber, cordwood, stone, and ice

.

Yes, all that was needed, we boated, dear pal,

Best time of our lives we had on the canal

.

I will not be a rover, for I love my boat,

I am happy, contented, yes work, dream and float

.

My mules are not hungry, they're lively and gay,

The plank is pulled on, we are off on our way

.

64

Boatmen made anywhere from fourteen to twenty dollars a month, and some received around seventy-five cents to a dollar a ton for the coal they delivered. The company deducted 10 percent of their pay, and this money was given to them in January during the inactive winter. They always tried to make the return trip from Bristol to Easton profitable by carrying merchandise that arrived in Bristol's port for the local residents along the canal. If they were private captains, they paid tolls at several locks along the Delaware Canal. If they worked for the company, their boat number was logged and sent to the company.

A crew of three was required at the beginning of the canal age. In

The Whig

newspaper, on June 15, 1836, Supervisor Joseph Hough published this notice:

To boatmen on the Delaware Canal

It will hereafter be required for every boat navigating on the Delaware Division Pennsylvania Canal, to have a Steersman and Bowsman on each boat, either descending or ascending said Canal, and also a boy with the tow horse

.

That rule didn't last long once the company ascertained that a crew of two could handle operation of the boat. Having a smaller crew, however, left them more vulnerable to problems that would arise.

Traveling in an open boat along a readily accessible route, with a towpath on one side and a berm on the other and surrounded by deserted farmland for most of the trip, boatmen could be victimized by bandits. There was a canalboat captain named John Reigal who carried a pouch of gold pieces around with him to settle his debts and pay for his provisions. His fellow canal men told him how dangerous this was, but it took quite a while before he was convinced that putting his gold in a bank was safer. Reports of theft along the canal finally persuaded him.

It wasn't uncommon for people to “rob” coal from the hold when a captain left his boat for some reason, and that would reflect on him when the coal was delivered and weighed. Even some lock tenders would “raid” a boat and sell the extra coal to make some money.

In truth, many boatmen themselves benefited from selling coal along the route, and it was gravely frowned upon by the company, which hired a Pinkerton agent to investigate. The LC&N expected some of the coal on a boat to “disappear” and considered it a hazard of the business. It wasn't always deliberate on the part of the boatmen; the “shovellers” who took the coal off the boat at the destinations along the way weren't always very careful, and coal, called “sweepings,” accumulated at the bottom of the hold. Other times, the shovellers were careless on purpose, especially when a bottle of Bushkill whiskey was involved. In 1890, the company hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to find out who of the boatmen were the worst offenders, and they sent an undercover agent to hitch rides on the boats to observe. Although most of the boat captains were careful not to talk too much, the agent was able to report some captains. He even reported that at one of the hotels along the canal, the “hookers” would go onboard and carry off some of the coal for use in the hotel while the boatman went inside for a quick beer.

65

In the last years of the canal age, a seal was put on the hatches after the coal was loaded, and it didn't bode well for the boatmen if the seal was broken when they delivered their load.

The camelback bridges that crossed over the canal may be picturesque, but they were nuisances for the canal men. When a boat was light and riding higher on the water, clearance under the bridges was too low, and many boatmen were injured. Ill-behaved children and teenagers were known to throw rocks or food over the bridges at the canal men, then run away laughing. In some of the rougher areas along the route, there were incidences when containers of trash were thrown on the canalboats. In one episode, a canal man was cooking his breakfast on deck when one of the boys urinated down into the pan. The canallers' irritation was compounded by the fact that it was difficult for a canal man to jump off the boat in time to catch the miscreants.

The camelback bridges along the canal are picturesque, but boatmen considered them a hazard. There wasn't much headroom beneath the bridges, and people standing on them would sometimes throw rocks or garbage at the boats.

Courtesy of Historic Langhorne Association

.

And then there were the swimmers who thought nothing of grabbing onto the boat for a ride, which could create a delay or even damages to either the boat or the sides of the canal if the captain couldn't steer properly. Some captains were good-natured about it, and often the swimmers would acquiesce quickly and allow the boat to move on, but sometimes not. One captain reported in Yoder's

Delaware Canal Journal

, “So there were these two in a canoe who grabbed on my rudder. I said, âPlease get off it's hard for me to steer.'” When the two wouldn't comply, the captain went down into the cabin, grabbed his chamber pot and threw the entire contents onto the culprits. “You ought to see them dive for water. They took the boat number and from that time on we had no more trouble.”

66

Some captains realized that they would avoid more trouble if they were agreeable. Captain Joe Reed would let them get on and dive off, and before long the boys could be coaxed to let him move on.

Although there were 116 regulations devised by the canal commissioners at the beginning of canal operations in 1833, there were really only a few important rules that couldn't be violated. The passing rule was one of them. The loaded boats stayed toward the berm side, and the lighter empty boats moved along the towpath side, having the right of way. The towline of the loaded boat was dropped to the bottom of the canal so the approaching boat could pass over it. Every boat had to have a guard plate attached to the keel, extending under the rudder to cover the opening between the sternpost and rudder to prevent fouling the towline. If a boat was found without that guard, the captain would be penalized with a fine and have to pay for all damages.

Several covered bridges, like this one in Uhlersville, crossed over the canal and continue to be part of the Bucks County landscape today.

Courtesy of Historic Langhorne Association

.