The Delaware Canal (13 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

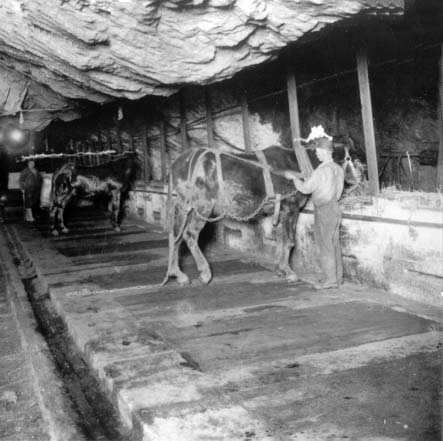

Mules were stabled underground in the mines where boys would care for them. They were rarely brought above ground after being put to work in the mines.

Courtesy of Robin G. Lightly, Mineral Resources program manager, Bureau of Mining and Reclamation, PA Department of Environmental Protection

.

The mules' compact builds were perfect for working in the narrow passageways of the mines. They lived deep in the mines, in stables that were cut out of rock and other materials located near the “cage,” where the miners entered and left. Some never saw the light of day, which is disturbing considering how much they love to roll in the grass and stretch their muscles after a long day of work. Yet, the mine bosses knew that the mules were important to the productivity of the mines, and the animals were well cared for, perhaps even more so than the human workforce. The stables were cleaned out daily and the mules were combed, checked for sores and fed well on oats, corn and alfalfa.

The boys who took care of the mules usually became very close to the animals, and some of them would even ask their mothers to pack sandwiches or fruit for their mules when extra food was available. Not that it was necessary since the mules would help themselves to whatever was in the boys' lunchboxesâeggs, pork chops, bananas, bread crusts. The boys even shared plugs of tobacco with their mules, and some of the mules grew so addicted to the tobacco that they refused to work until they were given their share.

54

According to Susan Campbell Bartoletti's book,

Growing Up in Coal County

, mineworkers came to depend on the intelligence of the mules and their good memories. Miners believed that mules knew their way through the tunnels better than anyone else did, and if they lost their way, they unharnessed the mule and allowed the animal to lead them to safety.

Their intelligence could be frustrating, however, since they knew exactly how many cars they were supposed to pull, and should a driver sneak another one on the train, the mule wouldn't budge until it was removed. It never paid for a mule driver to be mean to a muleâthe animal never forgot and usually got even no matter how long it had to wait to do so. Weeks after a boy would twist a mule's ear or beat him with a stick, he could count on receiving a kick in the stomach or seat of his pants.

Four-legged Canallers

Mine mules' lives were very different from those of the boat-pulling mules, just as life was different for the boys who drove the mules along the scenic canal than for those who worked in the black, dank atmosphere of the mines. Yet close relationships developed between the humans and the mules above ground just as they did below.

The mules that walked the canal were usually better “dressed,” too. Canallers would decorate their mules' harnesses with bells that jingled a melodious tune. The bells came in useful when a boat moved through dense fogâthe boatman at the rudder could steer by listing to the sound of the bells. Many of the mules wore straw hats that were tied under their chins with holes cut out on the brim to make room for their ears.

Sensible boatmen looked down on others who were cruel to their mules. They knew the invaluable contribution mules made in keeping the boats moving along the canal, and a good mule team, once it was trained properly, could travel the towpath and pull a boat without a driver for long stretches between locks.

In an article in the

Bulletin

, Grant G. Emery, once a canalboat captain, told reporter Henry R. Darling:

A half decent mule with any brains at all was a lot better than a horse. After a couple of trips, the mules knew the canal as well as we did. They knew when to start, stop, and slow down. You didn't drive the mules. You let them go by themselves

.

Inspectors made regular rounds on the towpath to check the condition of the mules, and a captain could be arrested for improper treatment of his mule. Emery recalled in Bill Yoder's

Delaware Canal Journal

:

They had a woman down there, she'd make you stop the mules and lift the collar; and, if there was a sore on his shoulder, you had to take that mule out, you couldn't use him. They'd slap a fine on you. She was all through the Delaware

.

55

Emery was referring to Eva Huston, who was the SPCA representative on the Delaware Canal at the time. Eva's concern was well-founded considering the complicated tack the boat-pulling mules had to wear, which included harnesses, fly nets in the summer and waterproof blankets to cover their backs and shoulders in stormy weather.

Of course, mules didn't always need someone else to “speak” for them when they weren't happy. Many mule drivers received a swift kick that would send them into the canal, and if the hoof hit them in the wrong place, it could mean a seriousâor even fatalâinjury.

Normally there would be a team of two mules, often three, and occasionally a horse would be part of the team. They were harnessed in tandem, with the lead mule in front and the second mule or horseâcalled the shafterâbehind the lead. There was what was called a spreader, which kept the traces (lines) spread between the first and second mule to protect their legs from becoming chafed. The mule that was attached to the towline was harnessed to a cross stick called a stretcher.

The mules would work a sixteen-hour day, resting only when the boat went through a lock, and they pulled their load at a steady pace of 2 to 4 miles per hour. They made the round trip from Mauch Chunk to Bristol and back, which was 212 miles, in seven or eight days. At the end of the day, when their harnesses were removed, they would lie down in the grass and roll in great delight, twisting their necks and flexing their legs. This was their way of relaxing, and it also revived them. In fact, if a boat was close to a lock or at the end of the canal near Bristol, but the mules were showing fatigue (and when they were tired, no amount of pulling, prodding or cajoling would get them to move), boatmen would unharness the mules, allow them to roll in the grass and then hitch them up again to make the last few miles to the basin of the canal.

Although feed bags were attached to their harnesses every four hours, sometimes mules that weren't muzzled would stop along the towpath to graze. They were especially fond of eating poison ivy. And, like the mules that lived and worked in the mines, boat-pulling mules were just as fond of tobacco. If a mule driver was careless enough to leave his tobacco in his back pocket, the lead mule would pull it out with his teeth, and trying to get it back could result in a swift kick.

Boatmen stabled their mules at night in private or company-owned stables along the canal. It cost fifteen cents to stable a mule for the night; twenty-five cents for two mules.

Courtesy of Jim and Tina Greenwood

.

The New Hope Canal Boat Company, with the help of Captain Dave, mule driver Charles and mules Dot, Dolly, Joe and Daffodil, keeps canal history alive during interpretive canalboat rides in New Hope.

Author's collection

.

Mules weren't fond of water, which also made them perfect for canal work. Where a horse might decide to take a swim in the canal, the mule would back away from it. They took drinks at overflows and sometimes in the canal, but kept a safe distance.

Occasionally, and always with great chaos involved, mules would fall or be pulled into the canal. If one mule went into the canal, the other was bound to follow since their tack bound them together, and if they weren't assisted out immediately, they would drown. When it happened, the mule driver or captain would try to cut the traces as quickly as possible, because the loss of a muleâor worse, a teamâmeant a loss that a captain may not be able to recoup.

The great inventor and head of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, Josiah White, found the intelligence of mules very interesting. As mentioned in an earlier chapter, when he completed the gravity railroad in Mauch Chunk, White decided that the mules that worked outside the mines would be carried down the mountain in specially built carsâcalled “wagons”âon the loaded train in order to save time. Once the coal was unloaded from the train, the mules would pull the empty cars back up to the mine. During an annual report of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, White included a note about the mules. It read:

So strong was their attachment to riding down, that in one instance, when they were sent up with the coal waggons

[sic],

without their mule waggons, the hands could not drive them down, and were under the necessity of drawing up their waggons for the animals to ride in

.

56

Miles of Mules

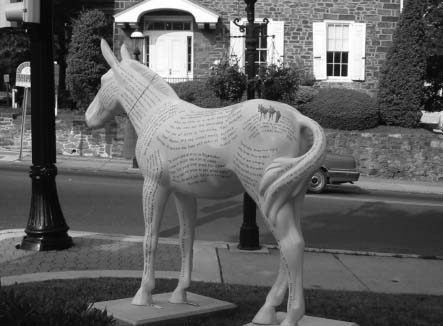

Mules are an icon of our national heritage because of the importance they played in the nation's economic development. In the summer of 2003, a public art project was launched throughout the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor; that is, towns and villages in Bucks, Lehigh, Northampton, Carbon and Luzerne Counties. The project featured more than 170 life-sized fiberglass mules.

The Miles of Mules program in Pennsylvania was sponsored by businesses, schools, individuals, families and nonprofit organizations. A committee of fifteen volunteers in Bucks County called the “Grooming Committee” reviewed artists' applications and ideas on how they wanted to decorate a fiberglass mule. When their applications were accepted, they received a $1,000 honorarium to cover expenses.

The mules were decorated by renowned local artists, amateurs and students who worked together to decorate the mules as school projects, all of whom used unique mediums and reflected their own styles and personalities or that of the region. There were traditional mules, colorful mules and sometimes outrageous mules, and all were unique. The project pulled together extensive community and business involvement. Once decorated, the mules were put on display throughout the region in public “paddocks” all along the canal corridor.

Rosemary Tottorato, who owns a graphic arts and communications company in Newtown, created a mule she called

Mule Tales

. Using this unusual medium, she wanted to communicate the important events that took place during the canal era. “The challenge was how to do it on a life-sized fiberglass mule.” She went to the National Canal Museum Archives in Easton for research, and then with two sizes of rubber stamps, Rosemary told the stories of the canallers by carefully stamping quotes and newspaper articles all over her white mule. It took her seventy-five hours to complete.