The Delaware Canal (14 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

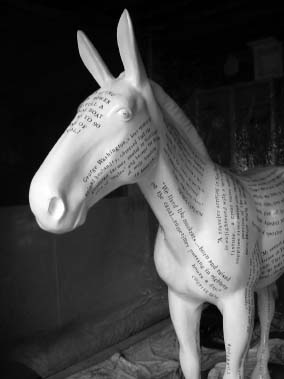

During the Miles of Mules project in 2003, 175 fiberglass mules were decorated by renowned artists, amateurs and students and placed in “paddocks” throughout the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor.

Courtesy Rosemary Tottoroto, Tutto Design and Communications

.

Using old newspaper articles and narratives by canal men, Rosemary Tottoroto tells the stories of the Delaware Canal in

Mule Tales

, which she designed for the Miles of Mules project.

Courtesy Rosemary Tottoroto, Tutto Design and Communications

.

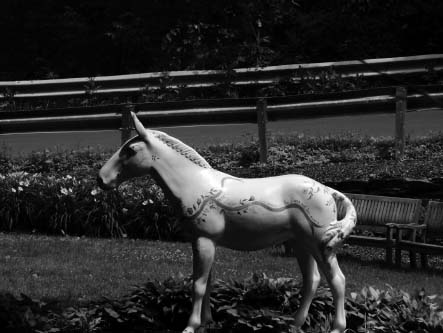

This whimsical mule decorates the gardens of the Golden Pheasant Inn in Erwinna.

Courtesy of Michel and Barbara Faure

.

Salvaged

, by artists Pete and Jennifer Miller, uniquely interprets the strength of the mule and the animal's “heart of gold.”

Author's collection

.

Sitting on the banks of the now quiet canal, Jim and Tina Greenwood's mule stands in tribute to the working animals that kept the canalboats moving from four o'clock in the morning until ten o'clock at night.

Courtesy of Jim and Tina Greenwood

.

Ben

was created by artist James Feehan and now lives in the garden of the lock tender's House No. 11. Surrounding

Ben

are John Thompson, Jack Thompson, Susan Taylor, Jan Wolters and Betty Orlemann.

Courtesy of the Friends of the Delaware Canal

.

When the “Summer of the Mules” drew to an end in November 2003, “The Mane Auction Event” was held in Bucks County, and forty-five of the decorated mules were sold at auction at the Michener Museum in New Hope. The proceeds of this auction benefited the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, the Michener Art Museum and other nonprofit groups such as Habitat for Humanity, Big Brothers Big Sisters of Bucks County, Artists in Residence, Fox Chase Cancer Center and many more worthy organizations.

Some of the owners of the mules have been kind enough to share them by displaying the mules around Bucks County for everyone to enjoy.

Chapter 8

The Canallers

Men, women and children worked the mule-driven canalboats from early spring to early winter, stopping only when ice prevented their boats from moving on the waterway. Babies were born on the canal, and death was a shadowy companion.

But who were they? How did their life's work become a boat, a mule team and a load of coal? Some of the earliest canal workers were from local towns and villages, farmers turned boatmen. Others were free men of color. Yet the majority of the canallers were drawn from the nineteenth-century immigrant pool, primarily the newly arrived Irish, Scotch and Germans. Some had worked in the anthracite mines, decided they couldn't take that life any longer and exchanged their Davy safety lamps for night hawkers. Others had worked on the excavation of the canal channel, and when it was complete, exchanged their shovels for rudders.

Immigrants to Pennsylvania in the colonial period were mainly English, with a large population of Germans (150,000 by 1775) and Scotch-Irish (175,000 by 1775). Approximately 5 percent of the population was French, Dutch, Welsh, Swedish, Jewish, Irish or Swiss. When the American Revolution began, the population of “Penn's Woods” had grown to nearly 300,000 and was one of the largest colonies in America with the most diverse population. After the American Revolution, immigration continued at a rate of approximately 60,000 a year, mainly from Western and Northern Europe. In the early and mid-nineteenth century, those numbers increased greatly with Germans fleeing Europe because of crop failure and religious persecution, and the Irish escaping the potato famine. Between 1830 and 1860âthe height of the canal ageâmore than 2,000,000 Irish and approximately 1,500,000 Germans arrived in America.

57

Many of these new immigrants made their way to Pennsylvania.

The German influence on both the Lehigh and Delaware Canals was very strong. In fact, on the Lehigh there were so many German canalboat captains and lock tenders that even the Irish and the African Americans who worked the canal learned the German dialect.

58

On the canal, the light boats returning to Easton had the right of way. Martha Best, whose laundry is hanging on the line of her husband's boat, steers toward the berm to allow LC&N boat 267 to pass.

Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Canal Society Collection, National Canal Museum, Easton, PA

.

The German Immigrants

For many years they were erroneously called “Pennsylvania Dutch,” but in fact, not all German-speaking immigrants were from the Netherlands. Many were Palatine German, Alsatian, Swiss, Hessian and Huguenot, and although they were primarily Quakers, German-speaking groups of various religious affiliationsâincluding Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptists (Amish, Hutterites and Mennonites) and Catholicsâalso settled in the colonies.

The earliest German immigrants in America came to Philadelphia County during the years 1683â85, and more came in the early 1700s. They left their European homes at the invitation of William Penn, whose First Frame of Government promised religious freedom and economic growth. Penn was particularly impressed with the organized Quakers in Holland and Germany long before he was granted land from the King Charles II, and when he was establishing his colony in America, he campaigned to persuade all persons interested in economic opportunity and freedom from religious persecution to immigrate to Pennsylvania by offering five-thousand-acre tracts of land at £100 per tract.

Germantown in Philadelphia County was where most of the German-speaking immigrants settled. In 1689, William Penn signed a charter incorporating Germantown, appointing Francis Daniel Pastorius as the first bailiff. (Later, Pastorius was to draw up a written protest against African slavery in 1688; it was the first in American history.)

All immigrants shared a common method of journeying to the shores of Americaâthey came by ship. Each voyage was unique, and some fared better than others, but there were many immigrants who did not survive. It was a common practice that when a ship approached the shore, the dead were brought off first and buried in ditches along the beach. Those who were left onboard faced the New World alone. Sometimes they were orphans; other times they were parents who had dreamed of a better life for their children but now had empty arms.

In Philadelphia, by the mid-1700s, there were sixty-five docks covering the west bank of the Delaware River, and those docks were crowded with new immigrants. When ships approached the shores of Pennsylvania, people gathered on the wharf, some to greet family members, others to find workers. Merchants were alerted by newspaper advertisements when German servants for “sale” were arriving by ship.

All the immigrant passengers disembarked and were taken to the courthouse, where they pledged an oath that they would conduct themselves as good and faithful subjects of the British Crown and that they would renounce any allegiance to the pope. They signed their names to two papersâone belonged to the king and the other to the government of Pennsylvania.

59

Many of the new colonists who had come with money didn't remain in Philadelphia. According to settlement patterns in southeastern Pennsylvania, they flocked to the countryside where they could purchase homesteads and begin to farm their landâtheir

own

landâhappy to have shrugged the yoke of tenant farming in their European homes. The farther away from Philadelphia, the more affordable land was. For the most part, Germans attempted to settle in pockets, since it was easier to communicate with each other and help one another when they planted their crops and built their homes.

Newly arrived Germans settled in Lancaster, Berks, Northampton, Bucks and Montgomery Counties. They walked over Native American paths through dense woods or traveled in canoes on the river and following Indian creeks to find their settlements. They brought with them skills as craftsmen and millers. They grew corn, squash and wheat in fertile soil, and they raised healthy livestock. Their barns were so well built and impressive that English settlers started to adopt their methods. And they established schools.

Before long, the Germans were holding public office. They worked diligently to establish their presence in their new country. They wanted religious freedom, a government that would allow them to control their own lives, land and success, all of which they found.