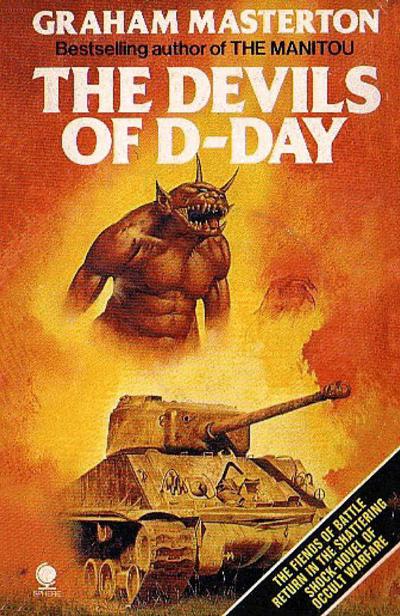

The Devils of D-Day

Read The Devils of D-Day Online

Authors: Graham Masterton

Tags: #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Fiction

The Devils of D-Day

by

Graham

Masterton

ARMY OF EVIL...

At

the bridge of Le Vey in July I944, thirteen black tanks smashed through the

German lines in an unstoppable all-destroying fury ride.

Leaving

hundreds of Hitler’s soldiers horribly dead.

Thirty-five

years later, Dan McCook visited that area of Normandy on an investigation of

the battle site. There he found a rusting tank by the roadside that was

perfectly sealed, upon its turret a protective crucifix.

Sceptical

,

he dared open it, releasing upon himself and the innocents who had helped him

an unimaginable horror that led back to that black day in I944. And re-opened

the ages-old physical battle between the world and Evil Incarnate...

From

today’s master of the occult thriller, here is a riveting, mega-chill novel of

modern-day demonism.

THE DEVILS OF

D-DAY

IS ABOUT A NEW

SATANIC KIND OF WAR.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

All of the devils and demons that

appear in this book are legendary creatures of hell, and there is substantial

recorded evidence of their existence. For that reason, it is probably

inadvisable to attempt to conjure up any of them by repeating out loud the

incantations used in the text, which are also genuine.

I would like to point out that the

Pentagon and the British Ministry of

Defence

strenuously deny the events described here, but I leave you to draw your own

conclusions.

-

Graham

Masterton

, London, 1979

I

could see them coming from almost a mile away: two small muffled figures on

bicycles, their scarves wound tightly around their faces,

pedalling

between the white winter trees. As they came nearer, I could hear them talking,

too, and make out the clouds of chilly

vapour

that

clung around their mouths. It was Normandy in December – misty and grey as a

photograph – and a sullen red sun was already sinking behind the forested

hills. Apart from the two French

labourers

cycling

slowly towards me, I was alone on the road, standing with my surveyor’s tripod

in the crisp frosted grass, my rented yellow Citroen 2CV parked at an ungainly

angle on the nearby verge. It was so damned cold that I could hardly feel my

hands or my nose, and I was almost afraid to stamp my feet in case my toes

broke off.

The men came nearer. They were old, with donkey-jackets and

berets, and one of them was carrying a battered army rucksack on his back with

a long French loaf sticking out of it. Their bicycle

tyres

left white furry tracks on the hoar frost that covered the road. There wasn’t

much traffic along here, in the rural depths of the Suisse

Normande

,

except for occasional tractors and even more occasional Citroen-

Maseratis

zipping past at ninety miles an hour in blizzards

of ice.

I called,

‘Bonjour,

messieurs

,’ and one of the old men slowed his bicycle and dismounted. He

wheeled his machine right up to my tripod and said,

‘Bonjour,

monsieur,

Qu’est-ce

que

vous

faites

?’

I said, ‘My French isn’t too good. You speak English?’

The man nodded.

‘Well,’ I said, pointing across the valley towards the cold

silvery hills, ‘I’m making a map.

Une

carte

.’

‘Ah,

oui

,’ said the old man.

‘

Une

carte

.’

The other old man, who was still sitting astride his

bicycle, pulled down his scarf from his face to blow his nose.

‘It’s for the new route?’ he asked me.

‘The

new highway?’

‘No, no. This is for someone’s history book. It’s a map of

the whole of this area for a book about World War II.’

‘

Ah, la guerre

,’

nodded the first old man.

‘

Une

carte

de la

guerre

,

hunk

?’

One of the men took out a blue packet of

Gitanes

,

and offered me one. I didn’t usually smoke French cigarettes, partly because of

their high tar content and partly because they smelled like burning horsehair,

but I didn’t want to appear discourteous – not after only two days in northern

France. In any case, I was glad of the spot of warmth that a glowing cigarette

tip gave out.

We smoked for a while, and smiled at each other dumbly, the

way people do when they can’t speak each other’s language too well. Then the

old man with the loaf said

,

‘

They

fought all across this valley; and down by the river,

too.

The

Orne

.

I remember it

very clear.’

The other old man said: ‘Tanks, you know?

Here,

and here. The Americans coming across the road from

Clecy

,

and the Germans

retreating back up the

Orne

valley. A very hard

battle just there, you see, by the Pont

D’Ouilly

. But

that day the Germans stood no chance. Those American tanks came across the

bridge at Le Vey and cut them off. At night, from just here, you could see

German tanks burning all the way up to the turn in the river.’

I blew out smoke and

vapour

. It

was so gloomy now that I could hardly make out the heavy granite shoulders of

the rocks at

Ouilly

, where the

Orne

river

widened and turned before sliding over the dam

at Le Vey and foaming northwards in the spectral December evening. The only

sound was the faint rush of water, and the doleful tolling of the church bell

from the distant village, and out here in the frost and the cold we might just

as well have been alone in the whole continent of Europe.

The old man with the loaf said, ‘It was fierce, that

fighting. I never saw it so fierce.

We caught three Germans but it was no difficulty. They were

happy to surrender. I remember one of them said: “Today, I fought the devil.” ‘

The other old man nodded.

‘Der

Teufel

. That’s what he said. I was

there. This one and me, we’re cousins.’

I smiled at them both. I didn’t really know what to say.

‘Well,’ said the one with the loaf, ‘we must get back for

nourishment.’

‘Thanks for stopping,’ I told him. ‘It gets pretty lonely

standing out here on your own.’

‘You’re interested in the war?’ asked the other old man.

I shrugged. ‘Not specifically. I’m a cartographer.

A map-maker.’

‘There are many stories about the war. Some of them are just

pipe-dreams. But round here there are many stories. Just down there, about a

kilometre

from the Pont

D’Ouilly

,

there’s an old American tank in the hedge. People don’t go near it at night.

They say you can hear the dead crew talking to each other

inside it, on dark nights.’

‘That’s pretty spooky.’

The old man pulled up his scarf so that only his old wrinkled

eyes peered out. He looked like a strange Arab soothsayer, or a man with

terrible wounds. He tugged on his knitted gloves, and said, in a muffled voice,

‘These are only stories. All battlefields have ghosts, I suppose.

Anyway,

le potage

s’attend

.’

The two old cousins waved once, and then

pedalled

slowly away down the road. It wasn’t long before they turned a corner and

disappeared behind the misty trees, and I was left on my own again, numb with

cold and just about ready to pack everything away and grab some dinner. The sun

was

mouldering

away behind a white wedge of

descending fog now, anyway, and I could hardly see my hands in front of my

face, let alone the peaks of distant rocks.

I stowed my equipment in the back of the 2CV, climbed into

the driver’s

scat

, and spent five minutes trying to

get the car started. The damned thing whinnied like a horse, and I was just

about to get out and kick it like a horse deserved, when it coughed and burst

into life. I switched on the headlights, U-turned in the middle of the road,

and drove back towards

Falaise

and my dingy hotel.

I was only about a half mile down the road, though, when I

saw the sign that said Pont

D’Ouilly

, 4 km. I looked

at my watch. It was only half past four, and I wondered if a quick detour to

look at the old cousins’ haunted tank might be worthwhile. If it was any good,

I could take a photograph of it tomorrow, in daylight, and Roger might like it

for his book. Roger

Kellman

was the guy who had

written the history for which I was drawing all these maps, The Days

After

D-Day, and anything to do with military memorabilia

would have him licking his lips like Sylvester the cat.

I turned off left, and almost immediately wished I hadn’t.

The road went sharply downhill, twisting and turning between trees and rocks,

and it was slithery with ice, mud and half-frozen

cowshit

.

The little Citroen bucked and swayed from side to side, and the windshield

steamed up so much from my panicky breathing that I had to slide open the side

window and lean out; and that wasn’t much fun, with the outside temperature

well down below freezing.

I passed silent, dilapidated farms, with sagging barns and

closed windows. I passed grey fields in which cows stood like grubby

brown-and-white jigsaws, frozen saliva hanging from their hairy lips. I passed

shuttered houses, and slanting fields that went down to the dark winter river.

The only sign of life that I saw was a tractor, its wheels so caked with ochre

clay that they were twice their normal size, standing by the side of the road

with its motor running. There was nobody in it.

Eventually, the winding road took me down between rough

stone walls, under a tangled arcade of leafless trees, and over the bridge at

Ouilly

. I kept a lookout for the tank the old cousins had

talked about, but the first time I missed it altogether; and I spent five

minutes wrestling the stupid car back around the way it had come, stalling

twice and almost getting jammed in a farm gateway. In the greasy farmyard, I

saw a stable door open, and an old woman with a grey face and a white lace cap

stare out at me with suspicion, but then the door closed again, and I banged

the 2CV into something resembling second gear and roared back down the road.

You could have missed the tank in broad daylight, let alone

at dusk in the middle of a freezing Norman winter. Just as I came around the

curve of the road, I saw it, and I managed to pull up a few yards away, with

the Citroen’s suspension complaining and groaning. I stepped out of the car

into a cold pile of cow dung, but at least when it’s chilled like that it

doesn’t smell. I scraped my shoe on a rock by the side of the road and then

walked back to look at the tank.

It was dark and bulky, but surprisingly small. I guess we’re

so used to enormous Army tanks these days that we forget how tiny the tanks of

World War II actually were. Its surface was black and scaly with rust, and it

was so interwoven with the hedge that it looked like something out of Sleeping

Beauty, with thorns and brambles twisted around its turret, laced in and out of

its tracks, and wound around its stumpy cannon. I didn’t know what kind of a

tank it was, but I guessed it was maybe a Sherman or something like that. It

was obviously American: there was a faded and rusted white star on its side,

and a painting of some kind that time and the weather had just about

obliterated. I kicked the tank, and it responded with a dull, empty booming

sound.

A woman came walking slowly along the road with an

aluminium

milk pail. She eyed me cautiously as she

approached, but as she drew near she stopped and laid down her pail. She was

quite

young,

maybe twenty-three or twenty-four, and

she wore a red spotted headscarf. She was obviously the farmer’s daughter. Her

hands were rough from pulling cows’ udders in cold dawn barns, and her cheeks

were bright crimson, like a painted peasant

doll’s

. I

said:

‘Bonjour, mademoiselle

,’ and

she nodded in careful reply. She said, ‘You are American?’ ‘That’s right.’