The Dragons of Winter (20 page)

Read The Dragons of Winter Online

Authors: James A. Owen

Tags: #Fantasy, #Ages 12 & Up, #Young Adult

Neither Uncas nor Quixote turned to look in the direction Aristophanes indicated, but simply dropped some coins on the table and followed him out the door.

The detective instructed Uncas to drive the Duesenberg back to the Summer Country, to a wooded hilltop in Wales, where he said they would camp for the night.

“This ought to be safe enough,” Aristophanes said as he removed his hat and ran his fingers through his hair. “The

Welsh mind their own business, and not everyone else’s.”

Both Uncas and Quixote, who were taking some camping supplies out of the boot of the Duesenberg, stopped short at the sight of the hatless detective. They had both known he was a unicorn, but thus far in their acquaintanceship, he had never removed the hat.

The base of his horn spread a full five inches across his forehead, like a thick plate of cartilage, and the markings from his having filed it down were easily visible. But from the base, a wicked-looking point had begun to grow, and it was already curving upward several inches from his brow.

“I like to grow it out when I’m working,” said Aristophanes. “And besides, where we’re going, no one will notice anyway.”

“No one noticing is pretty much why I don’t wear pants,” said Uncas.

“I like to sleep under the stars,” Quixote complained as he and Aristophanes unfolded the seemingly endless tent. “I really don’t see why we have to go to so much trouble.”

The Zen Detective nodded his head to the eastern horizon. “Those clouds are why. There may be weather later, and I’d rather not spend the night in a downpour, thank you very much.”

“I’d really rather have stayed at th’ Flying Dragon,” Uncas grumbled as he struck some flint to spark a fire.

“Not while we’re being observed,” said Aristophanes. “For all we know, that fellow was someone sent by Song-Sseu, to see what we’re using the parchment for.”

“She seemed like such a nice lady,” said Uncas.

“Everyone,” Aristophanes said as he handed his own knapsack

to the badger, “can be bought. Get the bedrolls set out. I have to go find a peach tree to water.”

“You have a peach tree in Wales?” asked Quixote.

The detective groaned. “I have to pee, you idiot.”

“Hey,” Uncas whispered as the detective cursed his way to the trees. “Look at this!”

It was the Ruby Opera Glasses. They were inside the knapsack.

“Manners, my squire,” Quixote scolded. “You shouldn’t be looking in his bag. And besides, those won’t do us much good out here, anyway.’

“They might,” Uncas disagreed, tipping his head at the tent flap. “Anyone can be bought, remember?”

The knight shook his head. “Being a thug for hire and giving oneself entirely to the Echthroi are different things. If he has simply been bought, the glasses wouldn’t show it, would they?”

“If he’s a Lloigor,” the badger replied, “they will.”

Quixote chewed on that thought a moment. It might be worth having a quick peek at the detective—just to be sure he was, as he claimed to be, on the side of the angels.

“What are you doing?” Aristophanes exclaimed as he suddenly entered the tent. “I told you those are only good for . . .” He made the connection and scowled, then smirked. “Oh. I see. Wanted to check out your partner, did you? You were wondering if I was an Echthros?”

“Technically, you’d be a Lloigor,” Uncas said as Quixote elbowed him in the arm. “Uh, I mean, well, yes. Sorta.”

“Hmph,” the Zen Detective grunted as he sat next to the old knight and opened a bottle. “I suppose I can’t blame you,” he said as he tipped back the bottle to have a drink. “Very well, then. If it’ll make you feel better, go ahead and have a look.”

With a nod from Quixote, Uncas held the opera glasses up to his eyes and peered through them at the detective.

“Well?” asked Aristophanes. “Satisfied?’

Uncas nodded and handed the glasses to Quixote. “He’s not one of them. Not a Lloigor.”

“You just needed to ask,” Aristophanes said, a genuine note of hurt in his voice. “I could have told you.”

“Not to degrade our already shaky position with you,” Quixote said, clearing his throat, “but couldn’t you just have lied?”

“Maybe,” said the detective, “but not about that. I’m a unicorn—we can’t be possessed by Shadows, nor can we lose our own. It’s one of our more useful features.”

“Ah,” exclaimed Quixote. “So that’s why Verne trusts you.”

“No,” Aristophanes corrected. “That’s why Verne uses me. He sent you two along precisely because he doesn’t trust me. And, it appears, neither do you.” Without waiting for a response, he got up and opened the tent flap. “I’m going to go stretch my legs. I’ll be back later . . .

“. . .

partners

.”

The way he said that last word left Uncas and Quixote both flustered enough that they couldn’t say anything. Worse, they realized there wasn’t much they

could

say. Aristophanes was right. They didn’t trust him. They hadn’t trusted him from the beginning.

“But Verne didn’t . . . doesn’t,” said Uncas. “Is it really any wiser of us if we chose to, just to avoid hurting his feelings?”

“Something I have learned in my long years as a knight,” said Quixote, “is that everyone rises to the level of trust they earn. Your part in that is to simply give him a chance to rise or fall as his actions dictate.”

The little mammal’s whiskers twitched as he looked from the knight to outside the tent and back again. At last he smacked his badger fist into the other paw. “Then I’ll do it,” he declared. “I’m going to trust him.”

Quixote nodded approvingly as his little companion busied himself with getting their bedrolls ready to sleep for the night—but inwardly, he felt a twinge of regret. Not that the little badger was so willing to be trusting, but because, in Quixote’s experience, such trust could be easily justified . . .

. . . and just as easily betrayed.

Outside, there was a flash of light, followed by a low rumble of thunder. Moments later the first drops of rain began to speckle the ground outside.

“Looks like Steve was right about the storm,” Uncas said as he rolled over to sleep. “G’night, sir.”

“Good night, my little friend,” Quixote replied as the rain began falling harder, and a second burst of lightning illuminated the tent.

The knight could see that outside, silhouetted against the firelight, the detective had once again donned his hat. The rain didn’t seem to be bothering him, so Quixote decided that rather than press the issue, he’d just follow Uncas’s example and go to sleep. The detective could do as he wished.

Quixote wondered as he blew out the light which choice Aristophanes might make, to justify or betray the trust the badger—the trust that both of them—were giving to him. And he wondered what Uncas was going to feel if they were proven wrong.

He was still wondering when, finally, he drifted off to sleep. It was still raining.

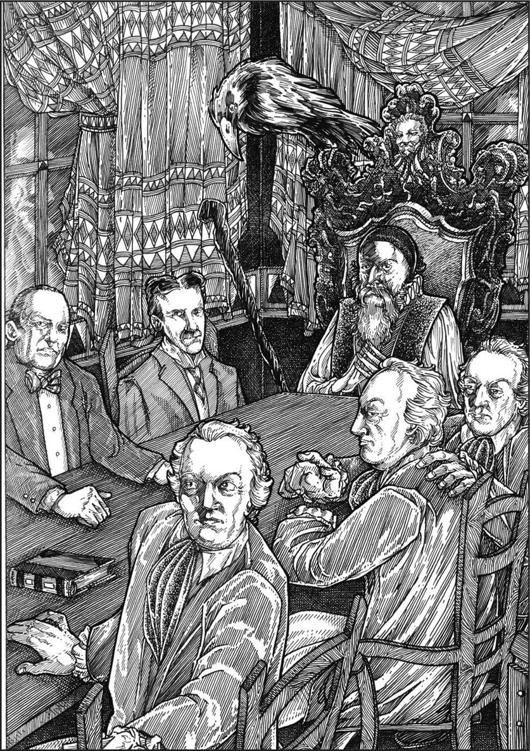

The Cabal seldom met in full quorum . . .

“I hope you’re ready

for another shock, young John,” Verne said as he put his arm around the shoulders of the man who had entered with Wells. “This is the true leader of the Mystorians, and the one without whom the Caretakers would have been lost long ago.

“John,” Verne continued in introduction, “I’d like you to meet William Blake.”

Almost involuntarily, John jumped backward, ignoring the man’s outstretched hand.

“Blake?”

he exclaimed angrily. “John Dee’s right-hand man? The second great betrayer of the Caretakers?”

“

My

right-hand man,” said Verne, “and the one who has given us what few actual advantages we have over the Cabal.”

“I understand your misgivings, John,” Blake said, unruffled by the younger man’s reaction, “but what I’m doing is very similar to Kipling’s own covert missions among the ICS—I’m just playing a deeper game.”

“It’s the idea that it is a game at all that bothers me,” John said testily. “Our circumstances are far more serious than that.”

“It is exactly that degree of importance that makes it a game

worth playing,” Wells cut in. “The Little Wars, the small games of conflict, and one-upmanship, all add up into history. The timeline of the world has ever been nothing but games.

“And,” he added, “as Heraclitus said, those who approach life like a child playing a game, moving and pushing pieces, possess the power of kings.”

“Is that what the Mystorians are?” John asked. “Kings playing games?”

“No,” Wells replied. “The Caretakers are the true kings. We’re just the ones who make sure no one removes you from the board.”

John sighed and turned to Verne. “I can see why he’s your secret weapon. He’s smarter than we are.”

Verne laughed, as did Blake. Wells merely smiled and removed his coat, nodding in greeting to the other Mystorians.

“It was always my strategy to use those whom I recruited only in their own Prime Time,” said Verne, “but then as events started to accelerate, I realized the value of having them available to consult with, and so in secret, we established the hotel, and this room, to better serve the cause.”

“Thereby having the help of men like Dr. Franklin both in life and in death,” said John. “I understand that. But why, ah, continue to work with them as ghosts, rather than create portraits, as with the Caretakers?”

“The portraits only work within the walls of Tamerlane House,” said Verne. “Outside, they would only last a week. And we needed to preserve the secrecy of our operations.”

John chuckled. “It almost seems like cheating,” he said blithely. “To continue to draw on all these great minds, after their deaths.”

“How is that any different from influencing the minds of those who read our books?” Carroll asked. “Or our overinflated autobiographies, in some cases.”

“Noted,” said Franklin.

“Your books are full of thoughts you’ve already, ah, thought,” said John, “but everything you’re doing here is . . .”

“New?” said Franklin. “So our influence should end, just because our earthly lives have?”