The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (20 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

Scientists who study oil depletion begin with the premise that, for any non-renewable resource such as petroleum, exploration and production proceed on the basis of the best-first or low-hanging fruit principle. Because petroleum geologists began their hunt for oil by searching easily accessible onshore regions of the planet, and because large targets are easier to hit than small ones, the biggest and most conveniently located oilfields tended to be found early in the discovery process.

The largest oilfields — nearly all of which were identified in the decades of the 1930s through the 1960s — were behemoths, each containing billions of barrels of crude and producing oil during their peak years at rates of from hundreds of thousands to several millions of barrels per day. But only a few of these “super-giants” were found. Most of the world’s other oilfields, numbering in the thousands, are far smaller, containing a few thousand up to a few millions of barrels of oil and producing it at a rate of anywhere from a few barrels to several thousand barrels per day. As the era of the super-giants passes, it becomes ever more difficult and expensive to make up for their declining production of cheap petroleum with oil from newly discovered oilfields that are smaller and less accessible, and therefore on average more costly to find and develop. As Jeremy Gilbert, former chief petroleum engineer for BP, has put it, “The current fields we are chasing we’ve known about for a long time in many cases, but they were too complex, too fractured, too difficult to chase. Now our technology and understanding [are] better, which is a good thing, because these difficult fields are all that we have left.”

4

The trends in the oil industry are clear and undisputed: exploration and production are becoming more costly, and are entailing more environmental risks, while competition for access to new prospective regions is generating increasing geopolitical tension. The rate of oil discoveries on a worldwide basis has been declining since the early 1960s, and most exploration and discovery are now occurring in inhospitable regions such as in ultra-deepwater (at ocean depths of up to three miles) and the Arctic, where operating expenses and environmental risks are extremely high.

5

This is precisely the situation we should expect to see as the low-hanging fruit disappear and global oil production nears its all-time peak in terms of flow rate.

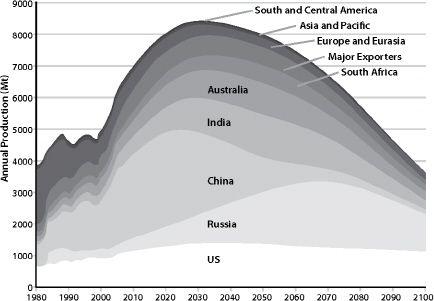

FIGURE 21.

Liquid Fuels Forecast, 1990–2035.

Source: International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2010.

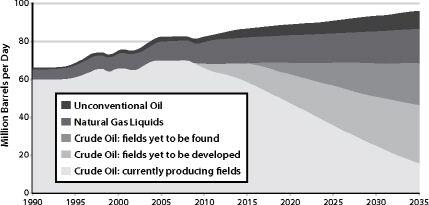

FIGURE 22.

World Oil Discoveries.

Source: Colin Campbell, 2011.

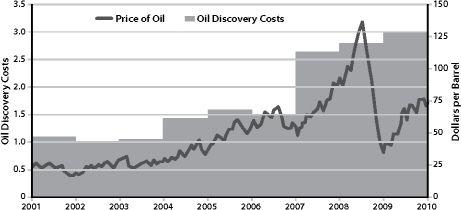

FIGURE 23.

Oil Discovery Costs.

Source: Thomson Reuters, Wood Mackenzie Exploration Service.

While the US Department of Energy and the IEA continue to produce mildly optimistic forecasts suggesting that global liquid fuels production will continue to grow until at least 2030 or so, these forecasts now come with a semi-hidden caveat:

as long as implausibly immense investments in

exploration and production somehow materialize

. This hedged sanguinity is echoed in statements from ExxonMobil and Cambridge Energy Research Associates, as well as a few energy economists. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that most serious analysts now expect a near-term (i.e., within the current decade) commencement of decline in global crude oil

and

liquid fuels production. Prominent oil industry figures such as Charles Maxwell and Boone Pickens say the peak either already has happened or will do so soon.

6

And recent detailed studies by governments and industry groups reached this same conclusion.

7

Toyota, Virgin Airlines, and other major fuel price-sensitive corporations routinely include Peak Oil in their business forecasting models.

8

Examined closely, the arguments of the Peak Oil naysayers actually boil down to a tortuous effort to say essentially the same things as the Peaksters do, but in less dramatic (some would say

less accurate and useful

) ways

.

Cornucopian pundits like Daniel Yergin of Cambridge Energy Research Associates speak of a peak not in

supply

, but in

demand

for petroleum (but of course, this reduction in demand is being driven by rising oil prices — so what exactly is the difference?).

9

Or they emphasize that the world is seeing the end of

cheap

oil, not of oil

per se

. They point to enormous and, in some cases, growing petroleum reserves worldwide — yet close examination of these alleged reserves reveals that most consist of “paper reserves” (claimed numbers based on no explicit evidence), or bitumen and other oil-related substances that require special extraction and processing methods that are slow, expensive, and energy-intensive. Read carefully, the statements of even the most ebullient oil boosters confirm that the world has entered a new era in which we should expect prices of liquid fuels to remain at several times the inflation-adjusted levels of only a few years ago.

Quibbling over the exact meaning of the word

“

peak

,”

or the exact timing of the event, or what constitutes “oil” is fairly pointless. The oil world has changed. And this powerful shock to the global energy system has just happened to coincide with a seismic shift in the world’s economic and financial systems.

The likely consequences of Peak Oil have been explored in numerous books, studies, and reports, and include severe impacts on transport networks, food systems, global trade, and all industries that depend on liquid fuels, chemicals, plastics, and pharmaceuticals.

10

In sum, most of the basic elements of our current way of life will have to adapt or become unsupportable. There is also a strong likelihood of increasing global conflict over remaining oil resources.

11

Of course, oil production will not cease instantly at the peak, but will decline slowly over several decades; therefore these impacts will appear incrementally and cumulatively, punctuated by intermittent economic and geopolitical crises driven by oil scarcity and price spikes.

Oil importing nations (including the US and most of Europe) will see by far the worst consequences. That’s because oil that is available for the export market will dwindle much more quickly than total world oil production, since oil producers will fill domestic demand before servicing foreign buyers, and many oil exporting nations have high rates of domestic demand growth.

12

BOX 3.2

The Mutually Reinforcing Conundrums of

Peak Oil and Peak Debt

The energy returned on the energy invested (EROEI) in producing fossil fuels is declining as we finish picking the low-hanging fruit. According to Charles Hall, who has conducted pioneering studies on “net energy analysis,” the EROEI for oil produced in the US was about 100 to one in 1930, declined to 30:1 by 1970, and then to 12:1 by 2005. EROEI figures for coal and gas are also declining

,

as the easily accessible, high-quality resources are used first.

As EROEI declines over time, an ever-larger proportion of society’s energy and resources need to be diverted towards the energy production sector.

Meanwhile, in the social sphere, since money comes into existence via loans but the interest to service those loans isn’t created at the same time, the amount of total interest due, society-wide, grows each year.

Thus in the same way that lower EROEI necessitates a shift in investment of energy and other resources from non-energy sectors of the economy towards the energy sector, the interest-servicing requirement of our monetary system diverts more and more resources from the non-finance productive economy towards interest payments.

The result: with time, less of both energy and money are available to support basic processes of production and consumption that drove economic growth earlier in the cycle and that support the needs of the population.

13

Other Energy Sources

Oil is not our only important energy source, nor will its depletion present the only significant challenge to future energy supplies. Coal and natural gas are also pivotal contributors to global energy; they are also fossil fuels, are also finite, and are therefore also subject to the low-hanging fruit principle of extraction. We use these fuels mostly for making electricity, which is just as essential to modern civilization as globe-spanning transport networks. When the electricity goes out, cities go dark, computers blink off, and cash registers fall idle.

As with oil, we are not about to

run out

of either coal or gas. However, here again costs of production are rising, and limits to supply growth are becoming increasingly apparent.

14

The peak of world coal production may be only years away, as discussed in my 2009 book

Blackout: Coal, Climate and the Last Energy

Crisis

. Indeed, one peer-reviewed study published in 2010 concluded that the amount of energy derived from coal globally could peak as early as this year.

15

Some countries that latched onto the coal bandwagon early in the industrial period (such as Britain and Germany) have been watching their production decline for decades. Industrial latecomers are catching up fast by depleting their reserves at phenomenal rates. China, which relies on coal for 70 percent of its energy and has based its feverish economic growth on rapidly growing coal consumption, is now using over 3 billion tons per year — triple the usage rate of the US. Declining domestic Chinese coal production (the national peak will almost certainly occur within the next five to ten years) will lead to more imports, and will therefore put pressure on global supplies.

16

We will explore the implications for China’s economy in more detail in Chapter 5.