The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (17 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

FIGURE 20A.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Allocation of funds of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. The economic stimulus bill passed by the Obama administration totaled around $790 billion, of which $665 has been spent so far. Of the $790 billion, close to 40 percent came not in the form of government spending, but rather in the form of lost revenues as a result of tax cuts. The second largest expenditure of the stimulus was the $90 billion allocated to states for Medicaid programs. Source: The Wall Street Journal, “Getting to $787 Billion,” February 17, 2009.

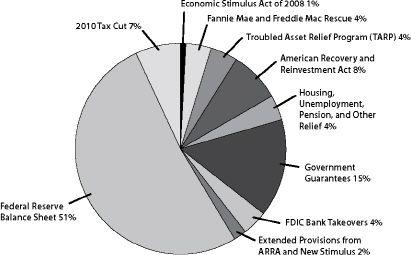

FIGURE 20B.

Stimulus and Bailouts — Maximum Amount Guaranteed.

Of the $11.8 trillion in funds allocated by the federal government for stimulus, bailouts, and bank guarantees, almost three quarters of the money comes in the form of an expanded Federal Reserve Balance Sheet and government guarantees for banks and other financial institutions. As of February 2011, not all of this money has been spent — only $4.6 trillion, of which $2.5 trillion has been added to the deficit. The remainder is on tap, to be used at the discretion of the Federal Government and the Federal Reserve. Source: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

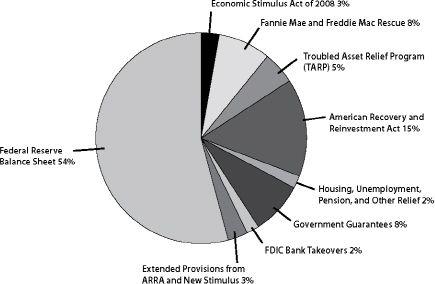

FIGURE 20C.

Stimulus and Bailouts — Amount Spent.

This chart shows a breakdown of the $4.6 trillion spent so far by the Federal Government to rescue the economy from collapse. The Federal Reserve spent the majority of the funds in order to stabilize systemically critical institutions. These expenditures took the form of loans, asset purchases, and guarantees. Source: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Actions By, and New Powers of, the Federal Reserve

While the US government stimulus packages were enormous in scale, the actions of the Federal Reserve dwarfed them in terms of dollar amounts committed.

During the past three years, the Fed’s balance sheet has swollen to more than $2 trillion through its buying of bank and government debt. Actual expenditures included $29 billion for the Bear Stearns bailout; $149.7 billion to buy debt from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; $775.6 billion to buy mortgage-backed securities, also from Fannie and Freddie; and $109.5 billion to buy hard-to-sell assets (including MBSs) from banks. However, the Fed committed itself to trillions more in insuring banks against losses, loaning to money market funds, and loaning to banks to purchase commercial paper. Altogether, these outlays and commitments totaled a minimum of $6.4 trillion.

Documents released by the Fed on December 1, 2010 showed that more than $9 trillion in total had been supplied to Wall Street firms, commercial banks, foreign banks, and corporations, with Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch borrowing sums that cumulatively totaled over $6 trillion. The collateral for these loans was undisclosed but widely thought to be stocks, CDSs, CDOs, and other securities of dubious value.

27

In one of its most significant and controversial programs, known as “quantitative easing,” the Fed twice expanded its balance sheet substantially, first by buying mortgage-backed securities from banks, then by purchasing outstanding Federal government debt (bonds and Treasury certificates) to support the Treasury debt market and help keep interest rates down on consumer loans. The Fed essentially created money on the spot for this purpose (though no money was literally “printed”).

In addition, the Federal Reserve has created new sub-entities to pursue various new functions:

•

Term Auction Facility

(which injects cash into the banking system),

•

Term Securities Lending Facility

(which injects Treasury securities into the banking system),

•

Primary Dealer Credit Facility

(which enables the Fed to lend directly to “primary dealers,” such as Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, which was previously against Fed policy), and

•

Commercial Paper Funding Facility

(which makes the Fed a crucial source of credit for non-financial businesses in addition to commercial banks and investment firms).

Finally, while remaining the supervisor of 5,000 US bank holding companies and 830 state banks, the Fed has taken on substantial new regulatory powers. Under the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, known as the Dodd-Frank law (signed July 21, 2010), the central bank gains the authority to control the lending and risk taking of the largest, most “systemically important” banks, including investment banks Goldman Sachs Group and Morgan Stanley, which became bank holding companies in September 2008. The Fed also gains authority over about 440 thrift holding companies and will regulate “systemically important” nonbank financial firms, including the biggest insurance companies, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc., and General Electric Capital Corp. It is also now required to administer “stress tests” at the biggest banks every year to determine whether they need to set aside more capital. The law prescribes that the largest banks write “living wills,” approved by the Fed, that will make it easier for the government to break them up and sell the pieces if they suffer a Lehman Brothers-style meltdown. The Fed also houses and funds a new federal consumer protection agency (headed on an interim basis, as of September 2010, by Elizabeth Warren), which operates independently.

All of this makes the Federal Reserve a far more powerful actor within the US economy. The justification put forward is that without the Fed’s bold actions the result would have been utter financial catastrophe, and that with its new powers and functions the institution will be better able to prevent future economic crises. Critics say that catastrophe has merely been delayed.

28

Actions by Other Nations and Their Central Banks

In November 2008, China announced a stimulus package totaling 4 trillion yuan ($586 billion) as an attempt to minimize the impact of the global financial crisis on its domestic economy. In proportion to the size of China’s economy, this was a much larger stimulus package than that of the US. Public infrastructure development made up the largest portion, nearly 38 percent, followed by earthquake reconstruction, funding for social welfare plans, rural development, and technology advancement programs. The stimulus program was judged a success, as China’s economy (according to official estimates) continued to expand, though at first at a slower pace, even as many other nations saw their economies contract.

In December 2009, Japan’s government approved a stimulus package amounting to 7.2 trillion yen ($82 billion), intended to stimulate employment, incentivize energy-efficient products, and support business owners.

Europe also instituted stimulus packages: in November 2008, the European Commission proposed a plan for member nations amounting to 200 billion euros including incentives to investment, lower interest rates, tax rebates (notably on green technology and eco-friendly cars), and social measures such as increased unemployment benefits. In addition, individual European nations implemented plans ranging in size from 0.6 percent of GDP (Italy) to 3.7 percent (Spain).

The European Central Bank’s response to sovereign debt crises, primarily affecting Greece and Ireland but likely to spread to Spain and Portugal, has included a comprehensive rescue package (approved in May 2010) worth almost a trillion dollars. This was accompanied by requirements to cut deficits in the most heavily indebted countries; the resulting austerity programs led, as already noted, to widespread domestic discontent. Greece received a $100 billion bailout, along with a punishing austerity package, in the spring of 2010, while Ireland got the same treatment in November.

A meeting of central bankers in Basel, Switzerland, in September 2010 resulted in an agreement to require banks in the OECD nations to progressively increase their capital reserves starting Jan. 1, 2013. In addition, banks will be required to keep an emergency reserve known as a “conservation buffer” of 2.5 percent. By the end of the decade each bank is expected to have rock-solid reserves amounting to 8.5 percent of its balance sheet. The new rules will strengthen banks against future financial crises, but in the process they will curb lending, making economic recovery more difficult.

After All the Arrows Have Flown

What’s the bottom line on all these stimulus and bailout efforts? In the US, $12 trillion of total household net worth disappeared in 2008, and there will likely be more losses ahead, largely as a result of the continued fall in real estate values, though increasingly as a result of job losses as well. The government’s stimulus efforts, totaling less than $1 trillion, cannot hope to make up for this historic evaporation of wealth. While indirect subsidies may temporarily keep home prices from falling dramatically, that just keeps houses less affordable to workers making less income. Meanwhile, the bailouts of banks and shadow banks have been characterized as government throwing money at financial problems it cannot solve, rewarding the very people who created them. Rather than being motivated by the suffering of American homeowners or governments in over their heads, the bailouts of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the US, and Greece and Ireland in the EU, were (according to critics) essentially geared toward securing the investments of the banks and the wealthy bond holders.

These are perhaps facile criticisms. It is no doubt true that, without the extraordinary measures undertaken by governments and central banks, the crisis that gripped US financial institutions in the fall of 2008 would have deepened and spread, hurling the entire global economy into a depression surpassing that of the 1930s.

Facile or not, however, the critiques nevertheless contain more than a mote of truth.

The stimulus-bailout efforts of 2008–2009 — which in the US cut interest rates from five percent to zero, spent up the budget deficit to ten percent of GDP, and guaranteed trillions to shore up the financial system — arguably cannot be repeated. In principle, there are ways of conjuring more trillions into existence for such a purpose, as we will see in Chapter 6. However, in Washington the political headwinds against further government borrowing are now gale-force. Thus the realistic likelihood of another huge Congressionally allocated stimulus package is vanishingly small; if more trillions materialize, they are likely to appear in the form of Fed-funded bailouts or quantitative easings. The stimulus-bailout programs constituted quite simply the largest commitments of funds in world history, dwarfing the total amounts spent in all the wars of the 20th century in inflation-adjusted terms (for the US, the cost of World War II amounted to $3.2 trillion). Not only the US, but Japan and the European nations as well may have exhausted their arsenals.

But more will be needed as countries, states, counties, and cities near bankruptcy due to declining tax revenues. Meanwhile, the US has lost 8.4 million jobs — and if loss of hours worked is considered that adds the equivalent of another 3 million; the nation will need to generate an extra 450,000 jobs each month for three years to get back to pre-crisis levels of employment. The only way these problems can be allayed (not fixed) is through more central bank money creation and government spending.

Austrian-School and post-Keynesian economists have contributed a basic insight to the discussion: Once a credit bubble has inflated, the eventual correction (which entails destruction of credit and assets) is of greater magnitude than government’s ability to spend. The cycle must sooner or later play itself out.

There may be a few more arrows in the quiver of economic policy makers: central bankers could try to drive down the value of domestic currencies to stimulate exports; the Fed could also engage in more quantitative easing. But these measures will sooner or later merely undermine currencies (we will return to this point in Chapter 6).