The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (12 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

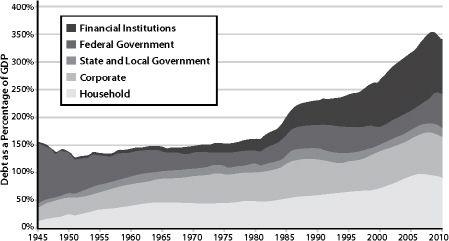

FIGURE 13.

Total US Debt as a Percentage of GDP, 1945–2010.

Percentages are based on nominal values of both debt and GDP for each year. Government debt (local, state, and federal) remains fairly constant as a percentage of GDP. It is household and financial sector debt that make the largest gains since 1945. We can see financial institutions begin to take on huge levels of debt beginning in the late 1980s, reaching a peak just before the crash of 2008. Source: The Federal Reserve, US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Also starting in the 1970s, economists and policy makers began arguing that, in order to end persistent “stagflation,” largely caused by high oil prices, government should cut taxes on the rich — who, seeing more money in their bank accounts, would naturally invest their capital in ways that would ultimately benefit everyone.

2

At the same time, policy makers decided it was time to liberate the financial sector from various New Deal-era restraints so that it could create still more innovative investment opportunities.

Some commentators insist that the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (since updated nine times) — which was designed to encourage commercial banks and savings associations to meet the needs of borrowers in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, and to reduce “redlining” — would later contribute to the housing bubble of 2000–2006. This notion has been widely contested. Nevertheless, the chartering by Congress of mortgage corporations Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 1968 and 1970 would certainly have implications much later, when the real estate market crashed in 2007.

3

But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

The process of deregulation and regulatory change continued for the next quarter-century. It included, for example, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, drafted by Senate Republican Phil Gramm and signed into law by Democratic President Bill Clinton in 2000, which legalized the trafficking in packages of dubious home mortgages.

These regulatory changes were accompanied by a shift in corporate culture: executives began running companies more for the benefit of management than for shareholders, paying themselves spectacular bonuses and putting increasing emphasis on boosting share prices rather than dividends. Auditors, boards of directors, and Wall Street analysts encouraged these trends, convinced that soaring share prices and other financial returns justified them.

4

America’s distribution of income, which had been reasonably equitable during the post-WWII era, began to return to the disparity seen in the 1920s in the lead-up to the Great Depression. This was partly due to changes in tax law, begun during the Reagan administration, which reduced taxes on the wealthiest Americans. In 1970 the top 100 CEOs earned about $45 for every dollar earned by the average worker; by 2008 the ratio was over 1,000 to one.

In the 1990s, as the surplus of financial capital continued to grow, investment banks began inventing a slew of new securities with high yields (and high risk). In assessing these new products, ratings agencies used mathematical models that, in retrospect, seriously underestimated their levels of risk. Decades earlier, bond credit ratings agencies had been paid for their work by investors who wanted impartial information on the credit worthiness of securities issuers and their offerings. Starting in the early 1970s, the “Big Three” ratings agencies (Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch) began to be paid instead by securities issuers. This eventually led to ratings agencies actively encouraging the issuance of high-risk collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).

Also in the 1990s, the Clinton administration adopted “affordable housing” as one of its explicit goals (this didn’t mean lowering house prices; it meant helping Americans get into debt), and over the next decade the percentage of Americans owning their homes increased 7.8 percent. This initiated a persistent upward trend in real estate prices.

The Internet as we know it today opened for business in the mid-1990s, and within a few years investors had bid up Internet-related stocks, creating a speculative bubble. The dot-com bubble burst in 2000 (as with all bubbles, it was only a matter of “when,” not “if ”), and a year later the terrifying crimes of September 11, 2001 resulted in a four-day closure of US stock exchanges and history’s largest one-day decline in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. These events together triggered a significant recession. Seeking to counter the resulting deflationary trend, the Federal Reserve sought to bring interest rates down so as to make borrowing more affordable.

Downward pressure on interest rates was also coming from the nation’s high and rising trade deficit. Every nation’s balance of payments must sum to zero, so if a nation is running a current account deficit it must balance that amount with funds earned from foreign investments, or by running down reserves, or by obtaining loans from other countries. In other words, a country that imports more than it exports must borrow to pay for those imports. Hence American imports had to be offset by large and growing amounts of foreign investment capital flowing into the US. Higher bond yields attract more investment capital, but there is an inevitable inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates, so trade deficits tend to force interest rates down.

Foreign investors had plenty of funds to lend, either because they had very high personal savings rates (in China, up to 40 percent of income is saved), or because of high oil prices (a windfall for oil-producing nations). A torrent of funds — a “Giant Pool of Money” doubling in size between 2000 and 2007 — was flowing into US financial markets.

5

While foreign governments were purchasing risk-free US Treasury bonds, thus avoiding much of the impact of the eventual crash, other overseas investors, including pension funds, were gorging on the higher yielding mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) and CDOs. The indirect consequences were that US households were in effect using funds borrowed from foreigners to finance consumption or to bid up house prices, while sales of mortgage-backed securities also amounted to sales of accumulated wealth to foreign investors.

Shadow Banks and the Housing Bubble

By this time a largely unregulated “shadow banking system,” made up of hedge funds, money market funds, investment banks, pension funds, and other lightly-regulated entities, had become critical to the credit markets and was underpinning the financial system as a whole. But the shadow “banks” tended to borrow short-term in liquid markets to purchase long-term, illiquid, and risky assets, profiting on the difference between lower short-term rates and higher long-term rates. This meant that any disruption in credit markets would result in rapid deleveraging, forcing these entities to sell long-term assets (such as mortgage-backed securities) at depressed prices.

Between 1997 and 2006, the price of the typical American house increased by 124 percent. House prices were rising much faster than income was growing. During the two decades ending in 2001, the national median home price ranged between 2.9 and 3.1 times median household income.

This ratio rose to 4.0 in 2004, and 4.6 in 2006. This meant that, in increasing numbers of cases, people could not actually afford the homes they were buying. Meanwhile, with interest rates low, many homeowners were refinancing their homes, or taking out second mortgages secured by price appreciation, in order to pay for new cars or home remodeling. Many of the mortgages had initially negligible — but adjustable — interest rates, which meant that borrowers would soon face a nasty surprise.

Wall Street had connected the “Giant Pool of Money” to the US mortgage market, with enormous fees accruing throughout the financial supply chain, from the mortgage brokers selling the loans, to small banks funding the brokers, to giant investment banks that would ultimately securitize, bundle, and sell the loans to investors the world over. This capital flow also provided jobs for millions of people in the home construction and real estate industries.

Wall Street brokers began thinking of themselves as each deserving many millions of dollars a year in compensation, simply because they were smart enough to figure out how to send the debt system into overdrive and skim off a tidy percentage for themselves. Bad behavior was being handsomely rewarded, so nearly everyone on Wall Street decided to behave badly.

By around 2003, the supply of mortgages originating under traditional lending standards had largely been exhausted. But demand for MBSs continued, and this helped drive down lending standards — to the point that some adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) loans were being offered at no initial interest, or with no down payment, or to borrowers with no evidence of ability to pay, or all of the above.

Bundled into MBSs, sold to pension funds and investment banks, and hedged with derivatives contracts, mortgage debt became the very fabric of the US financial system, and, increasingly, the economies of many other nations as well. By 2005 mortgage-related activities were making up 62 percent of commercial banks’ earnings, up from 33 percent in 1987.

As a result, what would have been a $300 billion sub-prime mortgage crisis when the bubble inevitably burst, turned into a multi-

trillion

dollar catastrophe engulfing the financial systems of the US and many other countries as well.

Between July 2004 and July 2006, the Fed began to pursue policies designed to raise interest rates on bank loans. This contributed to an increase in 1-year and 5-year adjustable mortgage rates, pushing up mortgage payments for many homeowners. Since asset prices generally move inversely to interest rates, it suddenly became riskier to speculate in housing. The bubble began deflating.

What Goes Up...

In early 2007 home foreclosure rates nosed upward and the US sub-prime mortgage industry simply collapsed, with more than 25 lenders declaring bankruptcy, announcing significant losses, or putting themselves up for sale.

The whole scheme had worked fine as long as the underlying collateral (homes) appreciated in value year after year. But as soon as house prices peaked, the upside-down pyramid of property, debt, CDOs, and derivatives wobbled and began crashing down.

FIGURE 14.

US Home Prices.

Conventional Mortgage Home Price Index since 1970. Home prices rose consistently from 1970 until their peak in 2007, with the steepest rise occurring after 2000. Source: Freddie Mac.

For a brief time between 2006 and mid-2008 investors worldwide fled toward futures contracts in oil, metals, and food, driving up commodities prices. Food riots erupted in many poor nations, where the cost of wheat and rice doubled or tripled. In part, the boom was based on a fundamental economic trend: demand for commodities was growing — due in part to the expansion of economies in China, India, and Brazil — while supply growth was lagging. But speculation forced prices higher and faster than physical shortage could account for. For Western economies, soaring oil prices had a sharp recessionary impact, with already cash-strapped new homeowners now having to spend eighty to a hundred dollars every time they filled the tank in their SUV. The auto, airline, shipping, and trucking industries were suddenly reeling.

Between mid-2006 and September 2008, average US house prices declined by over 20 percent. As prices dove, many recent borrowers found themselves “underwater” — that is, with houses worth less than the amount of their loan; for those with adjustable-rate mortgages, this meant they could not qualify to refinance to avoid higher payments as interest rates on their loans reset. Default rates on home mortgages exploded. From 2006 to 2007, foreclosure proceedings increased 79 percent (affecting nearly 1.3 million properties). The trend worsened in 2008, with an 81 percent increase over the previous year and 2.3 million properties foreclosed. By August 2008, 9.2 percent of all US mortgages outstanding were either delinquent or in foreclosure; in September the following year, the figure had jumped to a whopping 14.4 percent.