The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (13 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

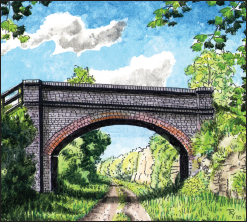

With the rebuilding of roads by turnpike trusts in the 18th century many new bridges were built. These were usually wider than earlier ones (although medieval bridges could have been widened) with long segmental arches and sometimes fashionable classical detailing on the keystone or parapet. Round and pointed arches were occasionally used but usually in parks or model villages where the architectural style was more important than the distance they could span. Around the turn of the 19th century cast-iron bridges were popular, being a cheaper and lighter structure than stone types, and then, in the 20th century, steel and concrete dominated as the road network expanded.

FIG 7.12 WYCOLLER, LANCS:

A rather distorted little packhorse bridge which demonstrates how masonry arches can withstand movement but still remain intact

.

River and coastal travel was an important method of moving large cargoes like masonry or timber around the country. The medieval boatman, though, faced just as many hazards and difficulties as encountered on land: flooding, drought, bridges which may not have been big enough to navigate through and weirs erected by millers to build up a head of water in order to turn their wheels, all made travel by boat unreliable. Although laws were put in place to clear obstructions it was not until the 17th century that the first major attempts were made to improve river navigation with new pound locks and short cuts around treacherous stretches. Those villages along navigable rivers benefited with wharfs giving them access to distant markets and employment around boatyards and maintaining the locks and weirs.

This form of travel, however, was no use if your quarry, mine, or factory was not near a suitable river or if you wanted to move goods across the country. The answer was to build canals and during the second half of the 18th and early 19th centuries thousands of miles of waterways were created linking industrial and agricultural areas with towns and cities. Unfortunately, the long-term commercial viability of the canals was limited by the dimensions of narrow locks (approximately 72 ft x 7½ ft), which therefore restricted the size of boat and more importantly the load it could carry. Although later ones were built wider, the restriction of the narrow locks somewhere along the journey affected the cost and speed of transporting goods, such that a large number of canals closed in the face of competition from the railways and roads.

FIG 7.13 ATCHAM, SHROPSHIRE:

An 18th-century Classical bridge with wide segmental arches and beautifully carved masonry. Behind it is the concrete arched bridge from the 1920s which replaced it

.

A canal could have benefited nearby villages with an increase in trade now they could transport agricultural produce and industrial goods cheaply and for greater distances. The building of wharfs, boatyards, and inns especially around canal junctions and flights of locks, also created employment and, as with the main roads of the day, drew housing towards them. Some villages were just a hamlet off the beaten track before the canal transformed them into bustling centres, only for the subsequent decline of the waterway to return them to obscurity. Just because a canal is not visible today does not mean there is not a disused one which was filled in, or it could be that one was surveyed and planned but never actually built. The documents, surveys and maps from these lost or failed projects may survive and along with the records of existing canals can shed light on the history of many villages.

FIG 7.14 AUDLEM, CHESHIRE:

A typical canalside scene with an inn, wharf and warehouse which could be found in many similar villages. The commercial decline of canals has meant that the original Georgian and Regency buildings were often never replaced

.

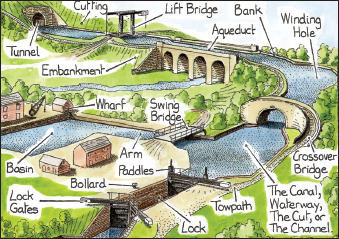

FIG 7.15:

A canal scene with labels of some of the common features which you can see today. Most villages close by would have had a wharf where local produce could be loaded and supplies like coal brought on land. Some were large with their own arm as here; others were just a building and crane alongside the canal

.

By 1830, when the potential of the new iron horses was realized, a massive network spread across the countryside in a matter of just a few decades. The speed and versatility of the railways quickly extinguished competition and transformed the villages which they served. Their priority initially was the transportation of goods and produce like milk, livestock, grain, fish, fruit and vegetables which could now be transported to distant markets as they would reach their destinations while still fresh. Natural commodities from the locality like stone, timber, clay, lime and slate, and products like iron and bricks could be moved in quantity for an expanding worldwide market, bringing increased profits to landlord, factory owner and farmer. At the same time they also brought coal into the village, which may have ended the coppicing of trees in local woods that had previously been the main source of fuel.

Although the arrival of a railway brought prosperity to many lowland regions, it was in the industrial, fishing and upland farming communities where the benefits were really felt, with a rapid expansion of hamlets into villages and even towns. As passenger travel developed and cheaper tickets became available in the second half of the 19th century, villagers could visit towns and cities they had previously only heard about, and the urban folk could go to the country or seaside as the train made a day trip a possibility for the first time.

In turn, though, the railways’ rigid routes and minimum viable loads could not compete with the more versatile road transport and from as early as the 1930s lines started to close. The Beeching Report of 1963 led to the sudden closure of a fifth of the railway network and a third of stations nationwide, though those which survived this threat are probably still running today. Searching the records of old railways and discovering where the stations and goods loading areas were situated can reveal which products were being transported, what the landscape around could have looked like then and how it affected the development of a village.

FIG 7.16:

Today, there are many signs of where railways once ran through villages. Old bridges, embankments and cuttings may survive, some like this example having been turned into longdistance trails. What appears as a wide speed bump in a road can be the site of an old level crossing while station buildings are often turned into homes or industrial estates. There may be a clue in a name, like a pub called the Railway Arms or Station Hotel

.

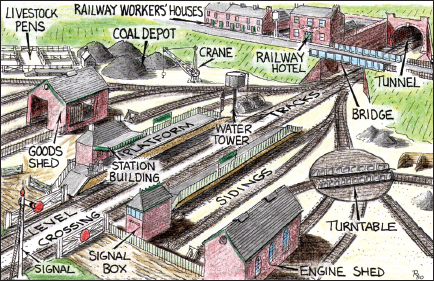

FIG 7.17:

A diagram showing some of the common features around a railway station which may still exist today

.

HAPTER

8

| Buildings |  |

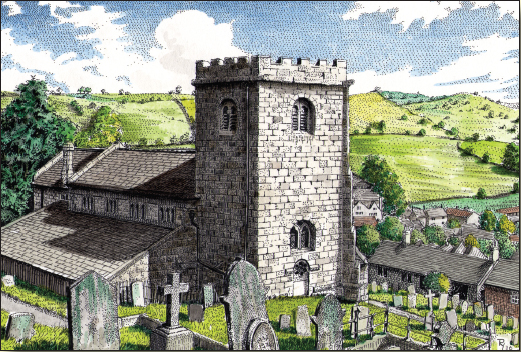

FIG 8.1. BRASSINGTON, DERBYS:

The church dominating the village below is just one of the major buildings which characterises settlements. This chapter explains the basic features and details by which these principal communal, agricultural and industrial structures can be recognised and dated

.

T

he church will usually be the oldest building in a village and even if a later edifice stands upon the site there will often be parts or fittings still evident from the earlier structure, like a section of original wall, a blocked Saxon window or an old font. Apart from those built from scratch in the past 300 years they are rarely all of one date. Most will have had parts rebuilt and additions made to

the ancient core and will today be a conglomeration of styles and forms. A church may even predate the settlement itself, having been founded in the early Saxon period when it served a group of surrounding hamlets, only for a village to be established around it later, perhaps when an open field system was introduced. Although there are around 15,000 medieval churches surviving today, each with its own peculiarities and regional characteristics, there are some common details and features which can help date the parts and often identify a prosperous period in a village’s history.

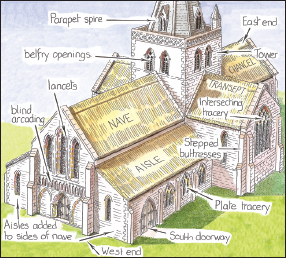

FIG 8.2:

A labelled drawing of a church as it may have appeared in the 14th century. Churches are laid out with the altar at the east end, a ceremonial doorway and often a tower at the west end and the everyday entrance to the south. The parts will usually be of different dates with towers, aisles and chapels being common later additions. Most walls were originally limewashed or rendered; the removal of this during restoration usually reveals a rustic patchwork of material showing where bits were added or repaired. The nave, which was the responsibility of the parish and hence could have a wealthy benefactor, was frequently reconstructed on a grander scale while the chancel in the hands of the poor priest was just patched up as parts wore out and may have been only rebuilt in the Gothic revival of the Victorian period. When churches have been excavated they are often found with a series of ever smaller foundations from earlier buildings under the floor of the nave, like a set of Russian dolls

.

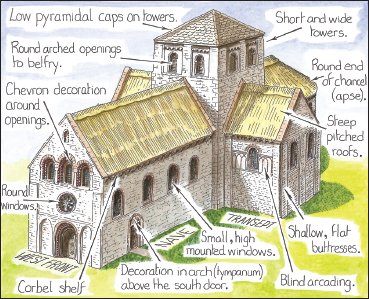

The earliest churches which survive today date from the 7th and 8th centuries and around 1,000 of them have parts or features which predate the arrival of the Normans in 1066. These are of stone, which at the time was an exclusive building material in most areas, so many of them could have been central minsters or associated with monasteries. Their distinctive characteristics are tall thin naves, thick walls, small round or triangular headed windows, doors with a semi-circular top and long and short stones up the corners. Most Saxon churches were built in timber and so have long since gone (though one example remains at Greensted, Essex).

The invading Normans brought with them experienced masons and as they became established in their new domain they began building churches primarily in stone. These late 11th and

early 12th-century edifices were still simple structures relying upon thick walls and stout columns to give them stability, which is revealed at window openings and doorways, both of which had semi-circular heads. Towers were rare at this date but those which the Normans erected tended to be in the centre between the nave and chancel and although many have since been replaced by a later structure at the west end, there may still be evidence of where they once stood. The chancel often had a semi-circular addition at the end called the apse in which the clergy could sit during mass; a few survive although there are many more Victorian copies. By the late 12th century these simple structures were becoming lavish in decoration with bands of figures under the eaves, receding bands of chevrons and other patterns around openings and dramatic scenes carved within the semi-circular head of doorways called a tympanum.

FIG 8.3 EARLS BARTON, NORTHANTS:

A late-Saxon tower with distinctive triangular and round arched openings and long and short stones up the corners. The vertical stone bands may have been replicating forms used on the more common timber churches at the time

.

FIG 8.4:

A drawing with labels of a large Norman church as it may have appeared when first built. Most buildings had thatched roofs and if there was a tower it might have had a low pyramidical roof. The outside was probably limewashed or rendered with splashes of colour picking out the decorative details

.

FIG 8.5 KILPECK, HEREFORD AND WORCS:

A notable late-Norman church with (from left) nave, chancel and the distinctive round apse. Many parish churches may have originally looked like this before having aisles, towers and large windows added in later centuries

.

FIG 8.6:

The inside of a medieval church would have been a riot of colour and full of mystery. Walls were painted with scenes from the Bible to warn an illiterate congregation of what would happen if they strayed from the faith. The various ceremonies and mass were conducted at the altar and in Latin, hidden from view behind the rood screen. The villagers standing in the nave (there would have been no pews) would have seen little and understood less of what was spoken or chanted. Wall paintings were whitewashed over during the Reformation and have only been rediscovered in the past hundred years or so during restoration

.

The introduction in the late 12th century of the pointed (Gothic) arch gave the builder more flexibility to create lighter structures with thinner walls, larger windows and finer columns. In its first phase, known as Early English, tall thin windows set in threes and fives called lancets were a distinctive feature. By the late 13th century the sections of wall between them were reduced to just ribs of masonry known as tracery, with simple geometric patterns at first but by early in the next century these had developed into elaborate curving and repeating designs, usually at their finest in the east window above the altar. This latter Decorated period of church architecture is also notable for elaborate doorways and window surrounds, often using an ogee arch (one with a reverse ‘S’-shape both sides) and spires. The booming population in the 13th and early 14th centuries demanded more space in which to pray. The easiest way of expanding the church was the addition of aisles, lean-to extensions along the north and south side of the nave with the old walls between cut through and fitted with columns. As these pushed the windows further back a row of small openings was made in the old wall above the columns, a clerestory, which allowed light into the nave.