The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (20 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

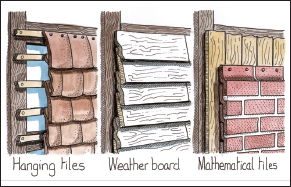

FIG 9.14:

In the north, many 17th- and 18th-century farmhouses were built with a barn as part of the structure. These laithe houses appear as larger versions of the old medieval longhouse but unlike the earlier types which were open into the byre the barns here were separate from the living quarters

.

FIG 9.15:

Fine quality 18th-century houses had symmetrical façades, sash windows and brick, stone or rendered walls scoured to look like masonry. Bay windows and fanlights as on the above example from Suffolk became fashionable in the second half of the century. The Venetian window in the middle has fine gauged bricks above which are distinctive of the Georgian period

.

FIG 9.16:

In the 18th century it was common to cover up old timber frames with cladding to disguise their outdated form. This could be done by coating plaster over strips of wood fixed to the front of the house, and then combing patterns into it. This process, called pargetting, was especially popular in East Anglia in the late 17th century, although most examples you see today are more recent. In coastal districts and across East Anglia, and later in the South-East, horizontal wooden boards were used as a weatherproof cover (centre). Hanging tiles were another form of covering used in the past, one which was also revived by Arts and Crafts architects (left). In the late 18th century mathematical tiles (right) could be hung on the outside to imitate brickwork (which also had the advantage of avoiding the brick tax from 1784 to 1850). By this time it was also common for cement to be applied to the front of the house to cover rough stone, poor timber and common brick and to give the rickety building Classic proportions. These refaced houses can be identified today by looking for an uneven level of windows, and for an exposed timber frame down the side and rear

.

FIG 9.17:

An early 19th-century house with a symmetrical façade, a central entrance halls, and fireplaces and chimneys on the end gable walls

.

The homes built before the industrial age for the labouring classes who made up the majority of the village population rarely exist today. What we generally regard as cottages were built for the better off, the houses constructed for and by the poor would only last a generation or two before needing rebuilding. From medieval times through into the 18th century in many places the single-storey long-house, with the family sharing one end and livestock the other (the byre), was a standard design found across the country. Its low walls would be made from local materials: stone where it could be collected off the fields, blocks of mud and straw, turf and flat stone slabs or flimsy timber frames filled with wattle and daub. Thatch was almost exclusively the roofing material and usually made from straw which the peasant would have as a by-product of his arable crop. Windows were unglazed with just shutters or animal skins to keep out the draughts, and there were no chimneys so the smoke from the fire just drifted up through the rafters.

FIG 9.18:

A medieval peasant’s longhouse, with the living space to one end and the byre for the livestock in the other

.

FIG 9.19 CASTLE HEDINGHAM, ESSEX:

Cottages could vary in form and materials but simple structures like these examples with dormer windows in the upper attic floor were widespread in the 18th and early 19th centuries

.

Improvements to labourers’ cottages were patchy and gradual, depending on the lord of the manor, local industry and individual success. In closed villages those workers that proved their worth might be rewarded with a fine quality stone or brick cottage for rent, often small in the 18th century but tending to be larger semis or terraces from the Victorian period. In open villages they could remain of more basic design but with less restriction on the occupants they could extend or rebuild with more freedom. In industrial villages and those influenced by canals and railways, rows of brick and stone terraces began to appear from the late 18th century, simple two up, two downs with a low front and casement windows (hinged to the side). By the mid Victorian period they were becoming taller with sash windows, and by the end of the century had rear extensions with a scullery.

The agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries hit labourers hard and although romantic pictures of tumble-down cottages from this period look charming they highlight what was often insanitary and undersized accommodation, often worse than in the city slums. It was only after the First World War that Government bodies started to erect council houses for agricultural workers, which still today line roads or form estates on the periphery of the village. These must have seemed like mansions to the first families moving into them! Another important development of the last century was the provision of mains water, sewerage and electricity. It is so often forgotten how very recently in historical terms some villagers were walking miles to collect water, suffering with insanitary conditions, and working by oil lamp and candlelight.

of a Village

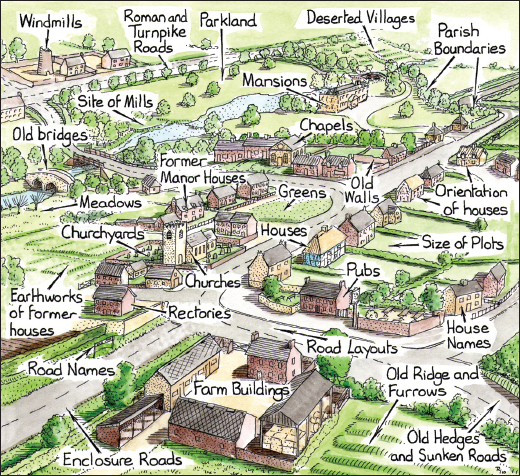

FIG 10.1:

Before burying your head in books and documents, it is worth spending some time walking around the village and surrounding fields and familiarising yourself with features and names. The above drawing lists some of the things to look out for. Having a first-hand knowledge of the area will make research a whole lot easier and it also may help identify some features which will be worthy of more detailed investigation

.

I

f

you have been inspired to look in closer detail at one particular place, then the following are some useful leads to take your studies further. Fortunately you do not have to be an historian or archaeologist to gain access to many of the documents and discoveries which can help you. There are books, TV programmes, magazines, evening classes, museums, history groups and local records offices. The internet has also made this process much easier and there are some suggested sites to try at the end of this section. Today the enthusiastic amateur with an open-minded approach and a bit of time can trace a surprisingly comprehensive village history.

These are essential tools in revealing the origins of villages. There are enthusiastic individuals and groups – including the English Place-Names Society – who have worked out the meaning of the different parts of the title of each village, and books are widely available listing them. Many are divided into two parts, the first often being an individual’s name, type of flora, or local topographical feature. The second part describes the type of settlement or setting for it and below are some common examples:

| borough | |

| or burgh | a stronghold |

| - by | a Norse word for a hamlet or farm |

| - don | a hill |

| - ey | an island |

| - ham | a homestead or meadow |

| - ing | the people of … |

| - ley | an area cleared of trees |

| - stead | general term for a place |

| - stock | site with stumps of trees |

| - stoke | smaller settlement |

| - stow | a place where people gathered |

| - street | a Roman road |

| - ton | a farm or estate |

| - thorpe | a Norse word for a hamlet |

| - thwaite | a Norse word for a clearing |

| - worth | an enclosure |

The interpretation of these details, however, is often more complicated and it is all too easy to get carried away and imagine the literal meaning as physical facts. For instance, the village Burham may be found to be ‘Beorn’s homestead’ as in Fig 2.5 but this does not mean he simply turned up and established a settlement which grew into the village. The name could be of the estate which an incoming Saxon or Viking had fought for, been rewarded with or simply purchased, and it was only at a later date that the farmsteads and hamlets within it formed into the central village, which retained the name of the estate. It is also possible that a new lord of the manor had an existing settlement, which may have been standing for centuries, renamed after him. Perhaps some were even named after important figures or by natives wishing to show respect to incoming invaders, as today there are cities named Victoria all around the old British Empire. It was also common in recorded times for Norman families to affix their names to that of an existing settlement, especially if it was

composed of more than one manor held by different lords. Sometimes the common name was later dropped, leaving just the family names applied to the present villages.

Field names can be of great importance and frequently record the presence of an old building or structures, the properties of the land, and previous uses of it. For instance, a mysterious mound which could be a Bronze Age burial turns out to be more recent when you discover it is standing in Windmill Field. These names may be known by the farmer or recorded on old estate, enclosure and tithe award maps.

If there is already a book published about your village, it will be worth reading, although try and digest the facts rather than opinions of the author as your interpretation of documents may differ. Do not let its presence put you off your own project, as previous writers may not have looked closely at the physical signs still present and the wealth of documents now available.

In addition to local studies there will also be a number of history books covering your county which may have additional information on your village and can be useful in showing how your settlement fitted into the local picture. For instance, the flow of traffic through my old village was north to south towards the nearest town, but it turned out that this had only sprung up in Victorian times around a new railway station. In reading the county history I found the nearest market before this was in a different direction, which explained why the older houses in the village were aligned on a west to east axis, and that what is now just a track was once the main road to this town. Some of these county histories can date back to the 19th or even earlier centuries and although their interpretation of ancient remains is dubious in the light of modern work, the facts they contain about what was then recent history can be invaluable.

From 1899 work started on a series of books to cover the history of every parish in every county of England. A hundred years on and the work is still continuing; some counties are complete while others are partly done, but only the West Riding of Yorkshire has nothing at all. If you are fortunate your parish will appear in one of the volumes held at your county or local library. Sections include the local geology and history of the manors, estates, churches and industries in and around your village. These are a fantastic starting point as they save you having to plough through old Latin documents to get an outline history of your community, although there will be further information available in your local records office.

There are fiction and non-fiction books written in the past which are very good at adjusting your mind to everyday life in a certain period. These can range

from the classics like Chaucer’s

Canterbury Tales

, written in the 14th century, to the diaries of country folk like Flora Thompson’s

Lark Rise to Candleford

. There may also be contemporary fiction which was set in your area, such as Thomas Hardy’s epics mainly based in Dorset, with many details of life at the time in between the tragic tales.

This series covering every county was written originally by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner in the 1950s and 1960s and describes and dates the buildings of architectural note within towns and villages. It is an essential guide for anyone interested in understanding more about old buildings although some of the old copies may have only brief entries. If your county has a new revised edition, it will be more comprehensive. Another important source is copies of surveys of listed buildings, which may be found in the county or local library; this should describe them with their appropriate grades, along with a short piece on features and dates. There may also be other books worth consulting on regional architecture but these will tend to concentrate only on major houses and the parish church.

Your county library or local museum should hold the records of regional archaeology and local history groups. Some publish a new book every year with reports from the latest digs down to the most minor of finds and their back catalogue can date from the mid 19th century. Most counties also have some form of monuments record which contains maps, aerial photographs and surveys of historic sites in the county.

From 1801 a national census has been held every ten years with the exception of 1941, although those from 1801 to 1831 are of limited use. Vital information can be obtained not only from the listings of village families and their occupations, but also from the population statistics produced by the government. All the censuses from 1841 to 1911 are available to search online, and record offices hold copies for their locality on microfilm.

Directories of professionals and tradesmen for towns or counties, and importantly the place where they worked within your parish, date back to the 19th century and again there are usually copies stored in your local library.

Since the turn of the 19th century the Ordnance Survey has been responsible for accurately mapping the country, and the earliest of the large-scale maps are a great source of information not only in how your village has developed but also in recording features and names which have since gone or been forgotten. The library should hold copies, while you can view or buy many online. From the 16th up until the 19th century, maps

were produced for local estates, or for enclosure acts and tithe awards. Although the older ones may not be accurate geographical surveys they are an excellent source of information and are one of the rare glimpses you may get into the physical appearance of your village in a bygone age.

There are countless books full of old photographs dating from the mid 19th century onwards, while local individuals and groups may hold other copies. They can be surprisingly useful in dating and understanding structures and buildings from their previous forms, as well as the social and economic state of the village.

Provincial newspapers appeared in the 18th century, and then boomed in the late 19th century. Old copies are usually held on microfilm at the county library. Magazines like

Country Life

can also be of historic value just as present-day publications like

Current Archaeology

can contain useful research and discoveries. The Newspaper Library of the British Library, based at Colindale, holds copies of all the newspapers and magazines published in this country.

Copies of the Domesday Book are widely available, so if your village was already established in the 1070s and 1080s it should be easy to find. It must be remembered though that William the Conqueror was interested in the value of an estate and not a physical description of a village or details of the people within, so an entry with the correct name might refer to a farm and not the village which was established nearby in later years.

The following describes just some of the important documents you may find useful, copies of which may be held at The National Archives, local records office, or the British Library

.

From the mid 16th until early 19th century the parish was the centre of local organisation and the records maintained are of immense value to the historian. The parish register in which christenings, weddings and burials were recorded is the most well known source, but other documents like parish accounts and records of the churchwardens, constables, overseers of the poor and surveyors of roads will also be enlightening. There are many other documents associated with the Church which can prove useful, including records of monasteries and their possessions, Church courts, and the visitations by senior clergymen to the parish.

There may be existing documents produced in the everyday running of the local estate, from lists of accounts and the records of the manor court, to the renting and selling of land and the surveys and maps associated with it.

There have been numerous surveys of

the population over the centuries for information and collection of taxes for kings, queens and their governments. The Domesday Book is probably the best known, but others include Hundreds rolls, poll tax, lay subsidy rolls, hearth tax, and muster rolls. The records of these can be fragmentary and it is worth consulting a book or expert about the interpretation of their contents, as well as the translation of some of the earlier ones. Judicial records of the various bodies of law also date back to the medieval period.

The most useful of personal records are probably wills and probate inventories in which were listed the processions of the deceased, helping to reveal the standards of living of the villagers. It is also worth enquiring to see if any family letters or personal diaries from past centuries have survived from within the parish.