The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (18 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 8.34 CLOVELLY, DEVON:

The quintessential English coastal village with vernacular housing clinging to the hillside above its little quay

.

HAPTER

9

| Dwellings |  |

FIG 9.1 LONGNOR, STAFFS:

Rustic stone houses and cottages lining the lane into this Peak District village complete the picture of an English village. Dwellings can range from grand mansions to Classical vicarages, and from large houses with three floors to single-storey cottages, the variety of the materials used and their form adding to the appeal of rural settlements

.

T

he estate of the Saxon thegn or medieval lord of the manor would have been managed from a large hall (although not every manor had one). It would have been important not just as a residence for the gentry and their entourage but also for the everyday running of the village and fields and the holding of the manor court. The earliest were timber halls, smaller versions of the medieval barns

you can visit today, and were usually set within a courtyard of outbuildings, surrounded by a wall and in some cases a moat. In the middle of the hall was an open hearth with the smoke from the fire escaping through a gap in the roof, while around it the lord and his entourage accepted guests, ate meals and slept communally.

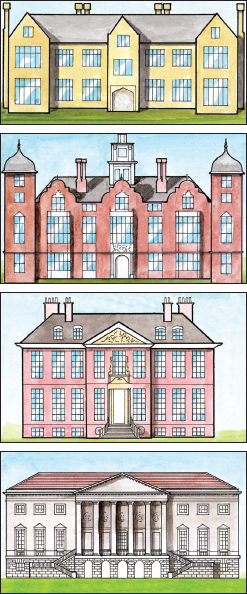

FIG 9.2:

In the north of England, where border skirmishes with the Scots were frequent, a defensive type of tower house developed from the 12th to the 16th century. The earliest ones were built for the upper end of the social order and would have stood within a walled enclosure like a castle, but by the 14th and 15th centuries lesser nobles and farmers were constructing modest versions with storage in the ground floor and a staircase accessing the upper hall and chambers. Where these survive today they are referred to as pele towers, their defended enclosures have gone and they are usually part of a later building as in this example, with a 16th-century extension to the left and a later wing in the foreground

.

By the 14th century taller timber-framed buildings were being erected with a large window at the end of the hall where the owner sat on a raised platform known as a dais. These new structures could be box-framed with individual walls made up of a grid of timber pieces raised into position to support the roof, which was popular in the south and east, or with cruck blades, pairs of matching slightly bent tree trunks fixed upright to form a row of upside down ‘V’s holding up the roof with low walls filling in the sides, which was more common in the north and west. Manor houses built in stone began to appear at the end of the 12th century for the wealthiest lords. In places where the stone was easily accessible, the house could take the form of a two-storey building with the main hall on the upper floor accessed by external steps or a ladder, while there was storage below in the undercroft. In the troublesome regions which bordered Wales and Scotland defensive walls, towers and moats could be added to form fortified manor houses, with only narrow window openings and access to the lower floors sometimes limited to an internal staircase.

The latest fashion accessory from the 13th century for your new manor house was a moat. Although originally a feature of castles it was rapidly becoming a cosmetic trimming in the less troublesome lowland parts of England. They may have been used for water storage or fish ponds but their primary purpose seems to have been to impress the guests. Hundreds of these survive as dry ditches in fields or still in water around farmhouses which themselves can contain architectural remains from the late medieval period, and can indicate where early manor houses would have stood.

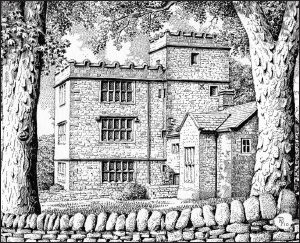

FIG 9.3:

Cut-away views with labels of key elements of medieval buildings of aisled (top), crucks frame (centre) and box frame construction (bottom)

.

In the later medieval period the lord of the manor and his family would have expected some privacy and a cross wing added to the top end of the hall was the most common way of creating chambers for them (the upper main room was known as the solar, although this name is also sometimes applied to the whole wing). A similar structure could also be added on the lower end of the hall in which certain food and drink was stored. The kitchen, due to its fire risk, was usually a separate structure

somewhere close to this service wing. In the Tudor period these forms of houses went through a radical makeover due to the addition of one new feature, the chimney. They had begun to be fitted to some large houses from the 14th century but by the 16th were fashionable with tall and elaborately decorated stacks on the finest examples. The old central hearth or smoke bay (a panelled-off end of the hall above head height to trap fumes) was replaced by fireplaces set in the wall, which meant the hall could now have a floor inserted creating a private chamber above in which the owner and his family could receive guests while the room below could be used by his household, completing the separation of the lord from his entourage.

FIG 9.4 STOKESAY CASTLE, SHROPSHIRE:

Although referred to as a castle, it is more of a fortified manor house built around 1290 for Lawrence of Ludlow, a successful wool merchant, with its defences protecting his cash rather than repelling armies. The large windows illuminate the hall and the steps at the left-hand end access the solar, the owner’s private chambers

.

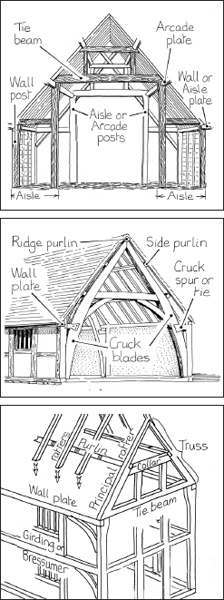

FIG 9.5:

From the 15th century medieval halls with an open fire (top) or a smoke bay up against the screens passage were fitted out with new fireplaces and chimneys so that a floor could be inserted to create a great chamber above (bottom)

.

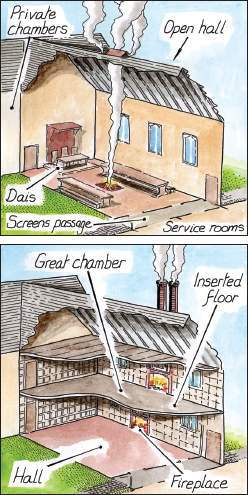

The role of the manor house as the place where the agricultural calendar was planned and from which judgements were cast was to gradually change as it became the country house – the grand home of dukes, baronets, lords and the gentry with its physical appearance and fashionable decoration designed to impress their ever-increasing guest list. During the 17th and 18th centuries new mansions were built at a comfortable distance from the village, or the village was moved a comfortable distance away! You can still find old timber-framed or stone buildings dating from the 13th to 16th centuries called ‘The Manor House’ within the village, while on the outskirts is the later mansion which superseded it. These new buildings were no longer vernacular, that is made from locally available materials using traditional methods, but became what is termed as Polite architecture, reflecting fashions from the Continent and being designed by architects (sometimes the owner himself). Timber-framed masterpieces like Little Moreton Hall were superseded by stone and brick mansions, often E-shaped in plan and with impressive displays of glass windows. By the late 17th century double-pile houses (two rooms deep) with hipped roofs and a line of white dormer windows above a symmetrical, flat Classical façade became fashionable. They in turn were replaced by Baroque with its tall sash windows, parapets hiding the roof, and bold decoration, only for the more refined Palladian style to dominate from the 1730s.