The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (19 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 9.6:

The development of English country houses, with an Elizabethan example (top), an early 17th-century Jacobean house with Dutch gables (centre top), a late 17th-century example with dormer windows (centre bottom) and an 18th-century Palladian house (bottom)

.

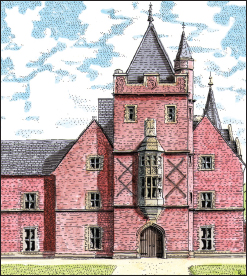

FIG 9.7:

In the mid 19th century the Gothic style of country house developed with an asymmetrical façade, Tudor and medieval style details and a love of towers and turrets

.

The Victorians erected huge Gothic, Italianate, Baronial, French and Classical mansions, often on the site of an earlier and now unfashionable house, while some new buildings especially for those who had made their money from industry and finance appeared on a fresh site. With large parties and hunting groups expected, the country house could develop into a massive complex with large service courtyards, stables and coach houses while many also had a tower, not just for display but to house the water tank to provide running water to taps. The 20th-century break up of these estates has seen many mansions converted into schools, hotels, military camps, and offices while some are now under the guardianship of the National Trust, English Heritage or private owners who open them to the public to help pay mounting bills. Surprisingly many though, were abandoned or demolished and in many villages it may be the old stable block, home farm or gatehouses which are the only remains to indicate their former glory.

FIG 9.8 WIGHTWICK MANOR, WEST MIDLANDS:

In the late 19th century architects gained inspiration from old manor houses and farmhouses rather than medieval churches. They revived traditional materials and methods of construction which flowered into the Arts and Crafts movement. Large houses in this period tend not to dominate the landscape but settle within it while timber-framed, stone, brick and rendered walls are juggled around to create an authentic appearance

.

FIG 9.9:

The 18th- or 19th-century vicarage will often be the most prominent large house after that of the lord of the manor, as in this example dating from 1716

.

The medieval local priest was often quite poor and lived in a house within the churchyard relying upon the tithe payment and his glebe on which to grow crops. The position of the clergy was elevated through the 17th and 18th centuries, as the local vicar or rector became better educated and was often the second son of a lord. He could now be married with a family, and benefit from the increased tithes due to agricultural improvements (a vicar was the incumbent of a parish where the tithes formerly were taken by a religious house or lord, while a rector was called such where the tithes had formerly been kept by the local priest). As a result they could build themselves finer houses to suit the genteel circles they mingled in, and old timber-framed cottages were replaced by impressive Classical houses with room for families and guests, while the church they were responsible for was largely ignored. With the new parishes and religious vigour of the Victorians many new brick and stone Gothic-style vicarages and rectories were built, only for economies in the last 50 years to see many sold off and replaced by more humble residences.

Houses

The successful farmers and merchants and later professional tradesmen, doctors and schoolmasters would have expected to live in a home of greater size and status than the labourers’ cottages around them. Only a few of these survive from the medieval period, some timber-framed with thick curving timbers and large panels, others in stone and brick usually of humble proportions. The growth in trade and agriculture from the Tudor period resulted in a housing boom starting in the south and east from the mid 16th century and spreading up into the uplands of the north and west by the 18th. This Great Rebuilding, as it has been termed, meant these successful members of the village could build themselves new houses, at first timber-framed with closely positioned verticals or decorative panels on the finest examples but then increasingly in brick. This had become popular in the eastern counties in the 15th century and spread progressively further south and west during the following 300 years although at this time it was an expensive product, usually made on site (local brickworks only became permanent in the 17th and 18th century or sometimes later) and was prominently displayed with decorative patterns picked out in grey bricks (daiper work). Stone was limited to where it was easily accessible and was often roughly hewn as there were few masons based in villages until the 17th century. These new houses and older ones which were renovated would have chimneys inserted; some brick and stone stacks were on an outside wall but many were built as stout blocks in the centre of the building and are distinctive when identifying houses from this period.

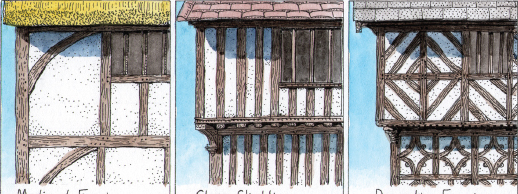

FIG 9.10:

Medieval frames had large panels with thick, sometimes irregular timbers (left). From the 15th century they became straighter with close studding (centre) and smaller square frames often with decorative inserts (right) found on the finest houses. The familiar black paint on the frame was a Victorian fashion, the exterior up until then could have been whitewashed all over or had the timber left to go grey with the panels in colours from off-white to pink and red

.

By the 18th century symmetrical-fronted houses, double-piled with three or five rows of sash windows across a plain façade, were within the scope of many of these individuals. Those who could not afford a new home would have older ones extended or re-fronted in the latest style. The new full time professionals and permanent tradesmen who grew in number during this period would either have outbuildings next to their modest houses in which to work or have new special structures built like a shop with accommodation above. Brick dominates the 19th century, replacing vernacular materials across the country. Some houses became asymmetrical, with finer quality materials, mass-produced decorative details and different coloured bricks inserted to enliven the façade. Masonry was more widely available from the 17th century as permanent quarries became established, with smooth square blocks and fine joints (ashlar) on the most exclusive houses and rougher stones with wider strips of mortar on the rest.

FIG 9.11:

A farmhouse for a prosperous yeoman dating from the late 16th century. The stout central chimney, with fireplaces below facing into the rooms either side, was the latest fashion and although the windows in this example were open with mullions (vertical divisions), glass was becoming widespread for houses of this class. The regular square panels and straight timbers are typical of this date

.

FIG 9.12:

Many timber-framed houses have the panels filled with bricks as in this example. This was sometimes done when originally built but more often is a later infilling (the bricks will be regular and sharp edged compared with 16th- or 17th-century ones which were thinner and variable in colour and shape)

.

FIG 9.13:

Houses built of stone and brick for the well-off members of the community became more widespread in the 17th century, as in this example with distinctive pointed gables with finials, cross-shaped windows and a large hood above the doorway (the latter feature common around 1700)

.