The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (17 page)

Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

FIG 8.27 GREAT COXWELL BARN, OXON (NT):

Erroneously called tithe barns, these huge structures were usually for storing monastic produce and not the tithe (the ten per cent of produce paid by villagers to support the local priest)

.

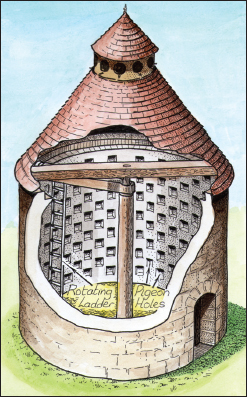

Another benefit of being lord of the manor was the exclusive right to own pigeons. In medieval times this food source, along with their eggs, was essential in maintaining a variety to the diet of a lord and his guests through the barren months of winter. They were typically tall, square or round planned structures with numerous recesses inside for the birds, and some type of ladder arrangement to enable their keeper to collect the eggs.

FIG 8.28:

A cut-away view of a dovecote showing the rotating ladder and holes. Sometimes these could be in the loft of a building, with holes in the gable wall

.

Inns and taverns can date back to the 14th century when they provided accommodation and refreshment for pilgrims and travellers along the main long-distance routes, their numbers booming in the 17th and 18th century. The village pub however, where locals could drink, only became common in its present form in the 19th century;

before this there were small alehouses, non-professional establishments which might be no more than a single room. Many Victorian breweries began running or building pubs with two bars, the ‘public’ with its games and gossip for the workers and the saloon fitted with superior furniture and a piano for the better-dressed clientele. Since the Second World War smaller family breweries have been bought out, with the dependant pubs either being forced to close or changing to suit the new owners, while the publican has become full time and has had to adapt to a wider social mix of clients and the drinks and food they demand.

Until the 19th century most villagers either grew their own food or bought it from the weekly market; any goods they required were either made at home or purchased from the craftsmen in the village, while special and exotic items could be bought at the annual fair. As markets declined and villagers, deprived of much of their land, became less self-sufficient, permanent shops appeared. With the introduction of the Penny Post in 1841 some shops took on the additional role of post office. The 20th century has not been kind to the village shop with newcomers to the community being more mobile and able to purchase their food from local towns. The invention of the car and the freezer has a lot to answer for! Shops have diversified to survive, selling all manner of goods, local crafts and paintings, and like the pub their success or failure can reflect the type of village which they now serve.

FIG 8.29:

Those villages which had a market but never made or retained their status as a town may still have buildings relating to it. Guildhalls (Thaxted, Essex, top), market houses, and butter crosses (Abbots Bromley, Staffs, bottom) provided shelter for stalls and often had space above for guilds and officials to meet

.

The parish constable (not a policeman in the modern sense until the mid 19th century but a local man who took on the duty of reporting on crime and disorder as an elected parish officer) would have had a lock-up to hold suspects, which could have been a small, single-cell square or round building or just part of an existing structure. Everyone is familiar with the scene of a man with head and arms dangling from a set of stocks while villagers throw rotten vegetables at him. These were used to dispense justice from the 13th to 19th centuries, although those which do survive, often preserved on the village green, are probably from the later period. Pounds, built to hold stray livestock, are more common but most have not been used since the parish fields were enclosed. Those which survive are built of brick or stone though many may have originally been just a fenced enclosure.

FIG 8.30: ALDBURY, HERTS:

This idyllic village, the backdrop for many films, comes complete with cottages, green, pond and an old set of stocks

.

Most village halls date from the last hundred years, after the formation of parish councils in the late 19th century. Some, however, are earlier, especially in estate villages where they were provided along with the communal package of church, school and water pump. It seems strange to think that some of the activities which today take place in the hall, like jumble, plant and cake sales, had their medieval equivalent held within the church itself!

The vast majority of village pumps were provided in the 19th century and are of the familiar dome-topped cast-iron variety, being very much a product of the industrial age. Some were presented to the village by the local lord or philanthropist and usually bear his name and a date. As mains water was laid on in the 20th century they became redundant and are rarely working today.

FIG 8.31:

The supply of water for a village is taken for granted today but has been a major problem for settlements in the past especially those in porous chalk and limestone regions. Where there were no reliable rivers, streams or springs, wells could be dug or ponds created, and rainwater off roofs collected. Little of this would have been consumed, though. Most people drank beer even at breakfast well into the 19th century. Village pumps, like this one at Hambleden, Bucks, and fountains were often supplied by a local benefactor, most dating to the second half of the 19th century. It was only in recent times that water towers in flat regions, raised up to create a good mains pressure, or reservoirs in hilly districts have been built to supply water to taps inside a house

.

FIG 8.32:

Buildings erected for a local industry can often be found in villages, like this imposing mill in Wildboarclough, Cheshire, built in the 1770s and used in recent years as a post office

.

Before the Industrial Revolution and the coming of the canals and railways most trades and crafts were carried out at home, either in an upper storey or cellar, or in a lean-to building or courtyard to one side. In fishing villages the preparation and storage of the catch was carried out in the same

places. It was not until improved transport became available in the early 19th century that larger-scale ventures could survive and purpose-built structures were erected for the task. Names on cottages and houses like ‘The Old Smithy’ may record a former use though the areas in which the business was actually carried on may have long since gone. Industrial-scale buildings can still be found in many villages, mostly dating from the past two centuries; some, like warehouses and breweries, may be easily identifiable while others will need further investigation using trade directories or old photographs to identify what they were used for.

FIG 8.33 BLAKENEY, NORFOLK:

This small port was planned as a town and superseded nearby Cley (see

FIG 5.4

) when its inlet silted up in the 1840s. The quay created in 1817 is mainly lined with warehouses built for the export of grain, with the gable ends facing the boats. As with many coastal settlements, decline in trade in the early 20th century was compensated for by increased tourism, in this case from bird-watching and sailing

.