The Extinction Club (8 page)

Read The Extinction Club Online

Authors: Jeffrey Moore

The two-storey Edwardian rectory was made of yellowish-brown stone, like the wicked witch’s gingerbread house, and its severely pitched roof, built to ward off heavy winter snows, was a crazy quilt of grey and green bandages. Thick icicles shot with turquoise hung from the eaves. The doors were dark chocolate, as were the shutters on the small windows. Out front was an ice-coated wrought-iron fence, and a rusting gate that ground its teeth to let me pass.

Around the back, on a hemp mat by the door, was a pair of large army boots covered in dried mud, and inside each were orange rubber gloves. A sign tacked to the door bore handwriting I recognized:

BEWARE OF CATS.

I turned round.

In the middle of the backyard was a pole with a bird feeder, its wooden ledges strewn with millet seed. Was the sign a warning to the birds? On tiptoe, I felt inside the box and pulled out a ring of keys embedded in frozen bird droppings.

The first room I entered was the kitchen. Red-brick walls and wide-planked pine floors. A great black stove, a big round table. Items scattered willy-nilly, scarily, on the floor, including bottles and plates and knives, but on closer inspection they seemed less the work of a vandal than someone preparing to clean.

The first cupboard I opened contained rows of hardcover books. The second cupboard I opened contained rows of hardcover books. The third cupboard … If I opened the fridge or stove, I had little doubt I’d see even more books stuffed inside, perhaps paperbacks. The fourth cupboard contained food, most of which was cereal, children’s cereal: Frosted Flakes, Froot Loops, Fruity Pebbles, Cocoa Krispies, Cocoa Puffs, Reese’s Puffs, Cap’n Crunch, Corn Pops, Count Chocula, Honeycomb, Honey Smacks, Lucky Charms … The genre is full of “k” sounds, I noticed, like swear words. On the bottom shelf were metal bowls with embossed paws and rubber trim, and stacked tins of Fancy Feast Turkey & Cheese, Chicken & Salmon, Grilled Tuna. The cats, evidently, were not vegetarians.

I began emptying tuna into six bowls set a foot apart. “Here, kitty kitty kitty …” I yelled out the door, several times. No response. But why

would

they respond to my voice? They need a good scent. I stacked the six bowls on top of each other, three in each hand, and carried them outside. Standing on the hemp mat, next to the size-12 army boots, I called again.

Two cats emerged out of nowhere and were soon purring at my feet, rubbing their shoulders against my ankles. One

white, one black, both half-starved. Two or three others were feral and raced away, while another lay on its back, crying mournfully. I set the bowls down.

Back inside, not wanting to cramp their style, I watched them through the kitchen’s bay window, whose sill was covered with dried mud footprints. Five cats ate ravenously, while the last one, a wary calico, crouched slowly, belly to the ground, toward the sixth and last bowl.

On the kitchen table was a pile of mail, which I nosily pawed through. Bills, for the most part, which I stuffed into my two coat pockets, and flyers, including one from the SAQ, the only place you can get liquor in this province. Instead of the regular price of $19.99, they were selling a Californian Pinot Noir for $19.49. Could I get there, I wondered, before the stampede?

There was a doggy door in the kitchen but no dogs in sight. I wouldn’t have minded seeing one or two. I’d always been a dog man. Not because I was scratched in the eye by a kitten when I was five, or because I saw a cat eat a chipmunk when I was seven, or because an Abyssinian killed my grandfather when I was nine, walking between his legs and sending him headfirst onto a Chippendale lowboy. No, it was because of their notorious aloofness, their refusal to come when you called, to show their glee when you arrived home. A virtue, according to many poets, including Swinburne:

Dogs may fawn on all and some

As we come;

You, a friend of loftier mind,

Answer friends alone in kind.

Just your foot upon my hand

Softly bids it understand.

After the food was devoured I went back out with bowls of water. While they drank, or at least while two of them did, I went for a quick stroll through the cemetery rows. The most sociable of the beasts, a fluffy white cat with a red collar, followed me. She made little runs and darts across my path, as if trying to trip me. I was mystified at first, but then wondered if this were a ruse to get herself lifted from the frozen ground and carried. It was. The cat not only let me pick her up, but seemed to demand it. She rode back to the rectory on my shoulder.

The room at the top of the stairs, obviously the grandmother’s study, was designed in a more-is-definitely-more style. It contained two leather chairs and a wall-length, floor-to-ceiling bookcase crammed with century- or half-century-old books on diverse subjects: William Beebe’s

The Bird, Its Form and Function

, Albert Camus’s

The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

, Rilke’s

Das Buch der Bilder

, Voltaire’s

Candide, The Book of Common Prayer, The Atheist’s Bible, Bring Up Genius!, L’Enfant prodige

… Many were dusty or discoloured by sunlight, while others, including E.M. Forster’s

Where Angels Fear to Tread, The Complete Poems of Hart Crane

and

The Life of P.T. Barnum, Written by Himself

, were library books with white Dewey decimals and Due Date cards from the forties.

Shrivelled houseplants and crumbs of soil were scattered over a red and white Persian carpet. A cat or some other animal had clawed the plants out of their pots. From behind a Salvation Army armchair, its arms savaged by cat claws, gleamed two pairs of masked eyes. Raccoons. When I

approached them they ran out the door with that humpbacked lope of theirs, claws clicking in the hallway. I listened as they scurried down the stairs and into the kitchen. Must lock that doggy door …

On the other wall, across from the bookcase, was a stone fireplace with an atlas cradled in mahogany where the grate should have been, and an Anglican Church of Canada flag above it: the red cross of St. George on a white background with four green maple leaves in the quarters. Next to this was a large wooden desk covered with papers and books and diverse objects, including ivory chessmen on an inlaid board, a Telefunken short-wave, very nearly Edison era, and a manual typewriter, a Smith Corona primed with paper and carbon. Before making typewriters, my grandfather told me, L.C. Smith was known for his shotguns.

On the discordantly papered wall above the desk, which cracked and curled at the cornices, was a local newspaper article about Céleste, about a college entrance exam she passed at the age of twelve. There was also a photograph of her and a woman with long grey hair sitting in a small aircraft, with Céleste at the throttle. The plane, which had metal plates on its wheels, was parked on a frozen lake. I looked closer at the older person, the grandmother presumably. Her face was craggy but finely boned. Both of them were beaming. I’d never seen Céleste smile like that, never seen her smile at all.

Down the hall, after opening two closet doors, I reached Céleste’s bedroom, which was an odd L-shape, a chess knight move. There were unaccountable cold spots in the room, as in a spring-fed lake, and its pine floor was filthy, covered with large mud footprints and traces of cloth swipes.

Like the rest of the rectory, the room contained more books than furniture. The house was a library. On the

top shelf of a long bookcase, a homemade affair made of bricks and particle board, were miniature animals in plaster or pewter. At least thirty of them, many of which I could identify: Tyrannosaur, Brontosaur, Titanosaur, Stegosaur, Hadrosaur, Albertosaur, Pterodactyl, Eohippus, Triceratops, Megalodon, Mastodon, Smilodon … We had something in common, Céleste and I.

On the sagging shelves below was an overflowing ashtray atop a stack of magazines, not those normally read by teenage girls—

The Philosophical Review, The New Atheist, Wildlife Forensics

—together with such books as

The God Delusion, Animal Farm, Dominion, The Ethical Assassin

…

On a high grey desk, whose top looked like a mortuary slab, was an opened copy of

North American Wildlife

with an ad circled in red:

BECOME A WILDLIFE DETECTIVE

Don’t be chained to a desk, computer or McCounter.

This easy home-study plan prepares you for an

exciting career in conservation and ecology!

Wildlife detectives find endangered species,

parachute from planes to help marooned animals,

catch poachers red-handed.

Live the outdoor life. Sleep under pines and stars.

Live and look like a million!

Live like a million?

What would that mean? I continued to snoop around. On the wall beside the desk was a note that said “World’s Most Dangerous Creature,” with an arrow pointing down, toward a full-length mirror. Next to this was a cartoon: in frame one, a hunter is aiming his rifle at a bear as it peacefully laps water from a pond; in frame two, the

stuffed bear is in the guy’s living room, ferociously baring fang and claw.

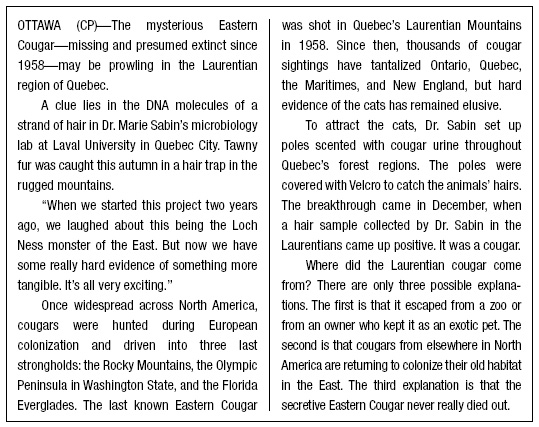

Thumb-tacked onto a bulletin board was a map of Paris, much used, along with overlapping newspaper clippings, at least a dozen of them, including this one from the

St. Madeleine Star

, December 1958. It was yellow with age and encased in plastic:

And this more recent one on the same subject:

With the smallest of the three keys I opened the bottom drawer of Céleste’s dresser, and promptly got a shock. A face looked back at me, from a ripped and blurred photograph of … the veterinarian. It was unmistakably her. I set this aside, thoughts whirling, and sifted through various sculpting implements—modelling tools, chisels, wire-loops, rods, dowels, netting—until finding a pair of glasses, the utopian communard model with small round lenses and frames of the thinnest wire. No doubt a spare, judging by their scratched lenses. Underneath all this was a blue sketchbook with tiny black letters on the cover. I had to put on Céleste’s glasses to read what they said:

NOT TO BE READ UNTIL I’M DEAD

.