The First 90 Days (52 page)

Authors: Michael Watkins

Tags: #Success in business, #Business & Economics, #Decision-Making & Problem Solving, #Management, #Leadership, #Executive ability, #Structural Adjustment, #Strategic planning

Sooner or later (probably sooner), though, you will need the support of people over whom you have no direct authority, within the company and externally. You may have little or no relationship capital with these people—no preexisting support and obligations on which to draw. Therefore, you will need to invest thought and energy in building a new base. Start early. It is never a good idea to approach people for the first time when you need something from them; you wouldn’t want to introduce yourself to your neighbors in the middle of the night when your house is burning down.

Discipline yourself to invest in building relationship capital with people you anticipate needing to work with later.

Think about how you have allocated your time to relationship building so far. Are there people you haven’t met yet who are likely to be critical to your success?

Identify the Key Players

How can you figure out who will be important for your success? To a degree, it will become obvious as you get to know the organization better. But you can accelerate that process. Start by

identifying the key interfaces

between your unit or group and others. Customers and suppliers, within the business and outside, are natural focal points for relationship building.

Another strategy is to

get your boss to connect you

. Request a list of ten key people outside your group whom he or she thinks you should get to know. Then set up early meetings with them. In the spirit of the golden rule of transitions, consider proactively doing the same when you have new direct reports coming on board: Create priority relationship lists for them and help them to make contact.

Another productive approach is to

diagnose informal networks of influence,

or what has been called “the shadow

[1]

organization” and “the company behind the organization chart.”

Every organization has such networks, and they

usually matter both in making change happen and in blocking change. These networks exist because people tend to defer to others whose opinions they respect on a given set of issues.

As a first step in coalition building, analyze patterns of deference and the sources of power that underlie them. How?

Watch carefully in meetings and other interactions to see who defers to whom on crucial issues. Try to trace alliances.

Notice to whom people go for advice and insight, and who shares what information and news. Figure out who marshals resources, who is known for taking pains to help friends, and who owes favors to whom.

At the same time, try to identify the sources of power that give particular people influence in the organization. The usual sources of power in an organization are

Expertise

Access to information

Status

Control of resources, such as budgets and rewards

Personal loyalty

You can use some of the techniques described in

chapter 2

on accelerating learning to gain insight into these political dynamics. Talk to former employees and people who did business with the organization in the past. Seek out the natural historians.

This document was created by an unregistered ChmMagic, please go to http://www.bisenter.com to register it. Thanks

.

Eventually you will be able to pick out the

opinion leaders:

people who exert disproportionate influence through formal authority, special expertise, or sheer force of personality. If you can convince these vital individuals that your A-item priorities and other goals have merit, broader acceptance of your ideas is likely to follow. By the same token, resistance from them could galvanize broader opposition.

You will also eventually recognize

power coalitions:

groups of people who explicitly or implicitly cooperate to pursue particular goals or protect particular privileges. If these power coalitions support your agenda, you will gain leverage. If they decide to oppose you, you may have no choice but to break them up and build new ones.

Draw an Influence Map

It can be instructive to summarize what you learn about patterns of influence by drawing an

influence map

like the one illustrated in

figure 8-1

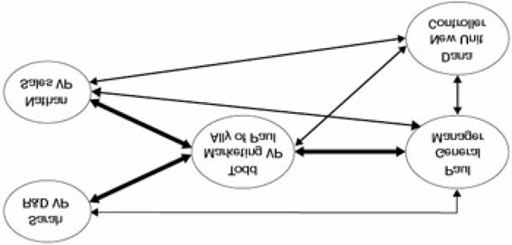

. It depicts both the flow and the extent of influence among members of a hypothetical business unit. Paul is the general manager of the unit. Todd is the VP of marketing and a long-time ally of Paul’s. Nathan and Sarah are VPs of sales and R&D, respectively. Dana, the new unit controller, has created this influence map in an effort to figure out how to advance some key initiatives.

Figure 8-1:

An Influence Map

The direction of a given arrow indicates who influences whom. An arrow’s width indicates the relative strength with which one individual influences another. Note that influence can flow both ways, depending on the issue. For example, Paul may influence Todd to set certain budgetary goals for marketing. Todd, in turn, may persuade Paul to authorize hiring new personnel.

Identify Supporters, Opponents, and Convincibles

The point of doing influence mapping is to help you identify supporters, opponents, and “convincibles”—people who can be persuaded with the right influence strategy.

Supporters

will approve of your agenda because it advances their own interests, because they respect you, or because they see merit in your ideas. To identify your potential supporters, look for the following: People who share your vision for the future. If you see a need for thoroughgoing change, look for others who have pushed for changes like those you are promoting.

People who have been quietly working for change on a small scale, such as a plant engineer who has found an innovative way to significantly reduce waste.

People new to the company who have not yet become acculturated to its mode of operation.

Whatever supporters’ reasons for backing you, do not take their support for granted. It is never enough merely to identify support; you have to solidify and nurture it.

Opponents

will oppose you no matter what you do. They may believe that you are wrong. Or they may have other

reasons for resistance to your agenda, such as the following:

Comfort with the status quo.

They resist changes that might undermine their positions or alter established relationships.

Fear of looking incompetent.

They fear seeming or feeling incompetent if they have trouble adapting to the changes you are proposing and perform inadequately afterward.

Threat to values.

They believe you are promoting a culture that spurns traditional definitions of value or rewards inappropriate behavior.

Threat to power.

They fear that the change you are proposing (such as a shift from team-leader decision making to team consensus decision making) would deprive them of power.

Negative consequences for key allies.

They fear that your agenda will have negative consequences for others they care about or feel responsible for.

When you meet resistance, try to grasp the reasons behind it before labeling people as implacable opponents.

Understanding resisters’ motives will equip you to counter the arguments your opponents will marshal. You may find that you can convert some early opponents. For example, you may be able to address fears of incompetence by helping people develop new skills. At the same time, it is essential not to waste valuable time and energy trying to win over staunch opponents.

Finally,

convincibles

are the swing voters: people who are undecided about or indifferent to change, and people you think you could persuade once you understand and appeal to their interests. Once you have identified convincibles, look into what motivates them. People are motivated by different things, such as status, financial security or wealth, job security, positive social and professional relationships with colleagues, and opportunities to tackle new and stimulating challenges. So take the time to try to figure out what

they

perceive their interests to be. Start by putting yourself in their shoes: If you were them, what would you care about? If it is possible to engage them directly in dialogue, then ask questions about how they see the situation, and engage in active listening. If you have connections to other people in their organization, then you should use them to learn. If you don’t, you might think about judiciously cultivating them.

Meanwhile, ask yourself whether there are competing forces that might tip convincibles toward resisting you. For example, making them see that their interests are compatible with yours would prompt them to support you, but the threat of losing a comfortable status quo might trigger resistance. Interests and competing forces should be part of what you undertake to learn about the politics of your organization through conversations, exploration of past decisions, and observation of group interactions.

[1]See D. Krackhardt and J. R. Hanson, “Informal Networks: The Company Behind the Chart,”

Harvard Business

Review,

July–August 1993.