The Girls from Ames (11 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

To his friends on the football team, Kurt could be just plain cool. He had this swaggering self-confidence and a slick way with words. He was always coming up with funny catchphrases that other boys would adopt. Years before it became famous in a Budweiser commercial, he’d walk around asking other guys, “Whazupp????” They’d repeat the phrase back to him, and there’d be laughs all around. “Whazuppp?!?!!” When the beer commercials first came out, those who’d lost track of Kurt wondered if somehow he’d gone into advertising.

Male friendships are often born on athletic fields, and in Kurt’s case, his bonds with other boys sometimes grew out of visceral physical confrontations. At one football practice, there was a scrimmage in which tailback Jim Cornette was pitched the football. Steamrolling right toward him at that moment was Kurt, playing defensive back. It was an almost maniacal charge. “We knew it would be a monster wreck,” Jim recalls. The two boys got within a couple of feet of each other and the coach blew the whistle. Both boys stopped. No contact was made. But for two decades after that, as their friendship grew, they’d kid each other. “I would have kicked your ass!” Kurt liked to say. And Jim would answer: “Yeah, right, I’d have flattened you and kept running!”

Jeff Sturdivant, the quarterback, was Kurt’s best friend starting in junior high. They were always comparing biceps or challenging each other to foot races. Jeff knew Kurt had a temper, ever since that party in eighth grade when a girl broke up with him and he put his fist straight through a wall. But when it came to Kurt, it was all part of the package. “He was very intense, but you were just drawn to him,” says Sturdivant.

A lot of boys idolized Kurt, and not just for his cockiness, his physicality and his sense of humor. They also were impressed that he had been able to woo Karla. By high school, boys were recognizing that she had grown into a beauty, and that she had this loving sweetness within her. Seeing her growing devotion to Kurt, they figured, maybe he also had something special inside of him, something he couldn’t easily reveal or articulate.

There were, however, people who thought otherwise. Some girls outside the jock sphere described him as arrogant. As for the ten other Ames girls, they certainly recognized Kurt’s charm and charisma, but they didn’t tell Karla everything they saw or thought.

Jane, for instance, had a story she chose not to share with Karla. Even though there were few Jews in Ames, Jane never really felt blatant anti-Semitism except once, from Kurt. It happened when she was in fourth grade and a bunch of kids had gathered after school to play kickball. They were picking sides when Kurt announced to everyone, “I don’t want that Jew on my team!” Jane never forgot the incident and never told Karla until they were adults.

In eleventh grade, Marilyn wrote in her journal that she felt uneasy watching Kurt lay into his younger brother “for taking some of his munchies.” That same day he spilled a beer on his brother for unknown reasons; Marilyn had to take out a hair dryer to dry the boy off. Though Kurt could be great fun, a part of him seemed out of control. Marilyn chose not to articulate any of this to Karla.

Angela knew something about Kurt, too. While he was dating Karla, he wasn’t always faithful. Once, even Angela made out with Kurt. They snuck into a bathroom at a party, and it happened. She didn’t feel right about it, of course, but she sensed that he probably fooled around with a lot of different girls. All the Ames girls had concerns about Kurt. But at least early on, no one believed Karla would stick with him.

Kurt had other issues, too. He was often mad at someone; there was always a reason. And because he took such pride in his toughness, other boys noticed that he’d often go looking for trouble. Once, after a football game, he got onto the bus filled with players from the opposing high school and started kicking and swinging at them. It was a dangerous decision. To bystanders, it was a surreal scene, as if one crazy guy had decided to declare an unprovoked war on an entire broad-shouldered army. Luckily, he wasn’t injured.

Jeff Sturdivant became a more devout Christian later in high school, and his friendship with Kurt ended. Still, even though the two boys were taking sharply different paths, he continued to admire Kurt from afar.

Boys in Ames couldn’t quite explain their feelings for Kurt or their need to impress him. “For some reason, we all just cared about him,” says Sturdivant, who ended up becoming an orthodontist in West Des Moines. “I guess it was because we loved him. That’s what it was. Even though I never saw him again after high school, as an adult I’d sometimes feel like I was reaching out to him, still trying to get his attention in some way. That’s a funny thing, but it’s the truth.”

A

s Karla became more involved with Kurt, she began spending all her time with him, which caused tension with the other Ames girls. It’s an old story, of course. A girl finally gets a boyfriend and puts him first. In Karla’s case, she still wanted to be with her friends, but she wanted Kurt there, too. So the Ames girls found themselves spending more time with him than they otherwise would have liked.

s Karla became more involved with Kurt, she began spending all her time with him, which caused tension with the other Ames girls. It’s an old story, of course. A girl finally gets a boyfriend and puts him first. In Karla’s case, she still wanted to be with her friends, but she wanted Kurt there, too. So the Ames girls found themselves spending more time with him than they otherwise would have liked.

Kelly considered Kurt to be braver, brasher and more confrontational than almost anyone she’d ever met, and she believed that’s what made him a good athlete. But she couldn’t figure him out. “He’ll try or do anything. He’s afraid of no one,” she’d say to the other girls. “Where does that come from?”

Karla had promised Kelly that after high school, they’d go together to the University of Iowa. They dreamed of establishing residency in California after that and finishing school together out there. Instead, at the last minute, without consulting the other girls, Karla decided to follow Kurt to the University of Dubuque, where he’d be playing football.

Kelly felt betrayed. She was also upset that her friend seemed to be choosing a boy over a chance for the best possible education. Just before leaving for the University of Iowa in Iowa City, Kelly went to an all-night party and, afterward, stopped in front of Karla’s house.

She sat in her car, scribbling a long, angry note. It was 6 A.M. when she finally placed it on Karla’s doorstep. Her basic message, as she recalls it, was this: “You’re giving up everything for a guy. You’ve bailed out on me. And you’ve bailed out on yourself. It’s a big mistake. You’re going to regret this decision.”

Kelly was right. Karla would go on to marry Kurt, and they would have a daughter, Christie, born in 1990. But Kurt wasn’t ready to be a parent or a loyal husband. Karla ended up leaving him when Christie was three months old.

T

wenty-seven years later, at the reunion at Angela’s, Karla isn’t thrilled that Kelly is psychoanalyzing her crankiness. When Karla says she isn’t feeling well—she has slight flu symptoms—Kelly’s diagnosis is that she’s homesick. “She’s really conflicted about being here,” Kelly insists. “She cannot bear to be away from her family. She hates it. And the minute she starts thinking about it, she wants to go home. She gets crabbier and crabbier.”

wenty-seven years later, at the reunion at Angela’s, Karla isn’t thrilled that Kelly is psychoanalyzing her crankiness. When Karla says she isn’t feeling well—she has slight flu symptoms—Kelly’s diagnosis is that she’s homesick. “She’s really conflicted about being here,” Kelly insists. “She cannot bear to be away from her family. She hates it. And the minute she starts thinking about it, she wants to go home. She gets crabbier and crabbier.”

“Kelly is full of it!” Karla later complains to Jane. “She says I’m sick because I’m homesick.”

“Don’t listen to her,” Jane advises.

And yet Kelly and Karla, despite this surface friction, have opted to be roommates. As the conversation between all the girls reaches deeper into the night, Karla can no longer keep her eyes open. She’d rather not be alone in the back bedroom. She wants her friend to join her. “Come on, Kelly,” she says, taking her by the hand. “It’s time to get some sleep.”

4

Sheila

O

n the second morning of the reunion, Jenny opens her suitcase and pulls out a shopping bag filled with old photos and letters, neatly tied in ribbons to differentiate each decade. There’s one photo in particular that she can’t wait to show the other girls.

n the second morning of the reunion, Jenny opens her suitcase and pulls out a shopping bag filled with old photos and letters, neatly tied in ribbons to differentiate each decade. There’s one photo in particular that she can’t wait to show the other girls.

She came upon it a few nights earlier in a closet at her home in Maryland, and at first, she was completely confused. It’s a five-by-seven portrait of her and a handsome football player named Dan, taken at the 1980 Ames High Christmas formal. The photo was still in the flimsy brown cardboard frame provided by that night’s photographer, who posed every couple in the exact same position.

Jenny had an unrequited crush on Dan for two full years. He’d never shown much interest in her, yet here he was, standing tightly against her in his white tuxedo and ruffled lime-green shirt, his hands in hers, smiling like she was his girl. “Wait a second,” Jenny thought. “I never went to any dance with Dan. What is this?”

When she looked more closely at the photo, she figured it out: Dan’s full body had been cut out of another formal photo and had been perfectly attached over the head and body of the boy who was Jenny’s actual date at that Christmas dance. To the naked eye, it was all incredibly seamless, as good as any mouse-clicking Photoshop user could produce today. Jenny held the photo in her hands for a couple of minutes, trying to do some mental detective work. And then she remembered.

“Sheila,” she said to herself, and couldn’t resist smiling.

One day back in 1980, Sheila had somehow gotten her hands on the photo of Dan and his real date, sliced Dan out of the picture, snuck into Jenny’s room at her house, found her Christmas formal photo, and done some fantasy editing. It wasn’t anything malicious; she wasn’t making fun of Jenny. As Jenny now recalls: “It was an act of love. It was just her way of saying, ‘Here you go. Here’s that picture of the two of you that you always wanted.’ ”

At the reunion, the other girls pass around the photo, laughing about Jenny’s oversized corsage and Dan’s oversized bow tie. They peek underneath to get a look at Jenny’s actual date in his gray suit. And they think about sweet, scheming Sheila with those scissors in her hand.

All the girls wish Sheila was here with them. It would be so fantastic to hear her recollections of how she doctored that photo. They’d have so much to ask her: What would she remember about the early years of their friendship that the rest of them don’t? What would be her take on all of their middle-aged issues?

“Remember how she laughed?” asks Cathy. “It was so great. It was never a put-on, either. When she found something funny, I mean, her laugh was just unaudited.”

The girls remember her childhood smile, too. “Sheila always smiled like she had a secret,” says Jenny.

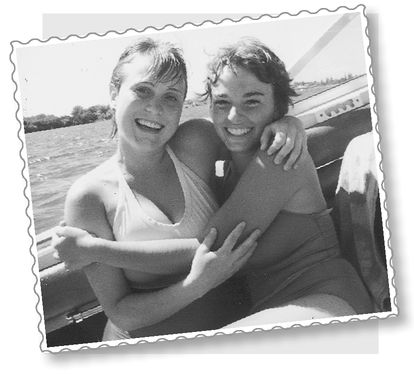

Angela and Sheila

In their heads, all the girls hold on to an image of Sheila, smiling away. The old photos help. But that laugh of hers, that’s harder to summon up, and they long to hear it again. It’s funny, they say, what you miss most about a person.

I

n the summer of 1979, Jenny and Karla went on vacation together to California, and Sheila sent them a letter. Almost all of it was devoted to bringing them up-to-date on her boy situation back in Iowa.

n the summer of 1979, Jenny and Karla went on vacation together to California, and Sheila sent them a letter. Almost all of it was devoted to bringing them up-to-date on her boy situation back in Iowa.

First, Sheila wrote, she went for a drive with their classmate Darwin, and though she was really excited to be with him, “we said absolutely nothing to each other.” Later she went to Doug’s house with Sally, Cathy and Angela. Darwin was there. “He was being weird and so was I (I was nervous),” so that ended up without much conversation, too. The next day, she talked to “Beeb, Joe and Wally,” a three-some whom she described, in order and very precisely, as “new, not cute, and sweet.”

The next night, Sheila went to a disco where she “tried to get rid of Steve.” Once he was out of the way, she danced with Joe, Dave, Randy and then Charlie. It was a fun night at the disco until one of the guys “got pissed at another guy”—over a girl, of course—and started pounding his fists into a wall until they were bleeding. “It was terrible,” Sheila wrote, before jumping to a new topic in her next sentence: “Oh, I found someone else to be in love with. His name is Jeff, but he’s only gonna be here a few more days.”

Sheila apologized that she wasn’t able to flesh out all the details of her adventures in this particular letter. To do that, she explained, “I’d have to write a book. Maybe I’ll do that when I’m old and lonely, but now I’m young and happy, so I’ll just write a chapter.”

When Jenny came upon Sheila’s letter in her closet, those last sentences jumped out at her because, of course, Sheila never got to live the full book. She was the Ames girl who never became a woman. When her friends think of her and speak of her, she’s always age seven or fifteen or nineteen—never more than twenty-two, the age she was when she died mysteriously. In their minds, she remains the carefree, boy-crazy teen they were.

“As we get older, I find myself thinking more and more about how much she missed out on,” says Angela. “What sort of man would she have married? What would she be telling us about her kids? Would she have worked? How would she look in her forties?”

The girls recall Sheila Walsh as vivacious, flirty, bubbly and busty. She had curly reddish-brown hair and got a kick out of experimenting with it; at one point she had this impossible-to-manage afro-like permanent. “Sheila was a little tiny thing, and just adorable,” says Sally. “She had these big brown eyes. And her family, they were the ‘Wow’ family—five kids, each of them gorgeous.”

Other books

Murder on High by Stefanie Matteson

Covenant's End by Ari Marmell

Singled Out by Simon Brett

Sins of Eden by SM Reine

To Reign in Hell: A Novel by Steven Brust

A Painted Goddess by Victor Gischler

A Duke Deceived by Cheryl Bolen

Angel Arias by de Pierres, Marianne

Dead Weight by Susan Rogers Cooper

Mad Max: Unintended Consequences by Ashton, Betsy