The Girls from Ames (7 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

At first, Dr. McCormack had great trouble coping with his son’s death. He asked that all photos of Billy be removed from the family room of their house; it hurt too much for him to look at them every day. He couldn’t bring himself to talk about Billy, either, and it upset him when well-intentioned people asked questions about his son or shared a memory of him. Years later, he’d become known in Iowa medical circles for his comforting bedside manner and his pioneering efforts to help people accept and live with loss. His hard journey to that role began with Billy’s death.

All grieving families struggle to find relief from their pain, and at some point in the months after the accident, Dr. and Mrs. McCormack developed a sense of what might help them. Their family felt so terribly out of balance. Maybe their three surviving children needed another sibling. Maybe they needed another child to love. Dr. McCormack, then thirty-five years old, decided he would try to reverse his vasectomy.

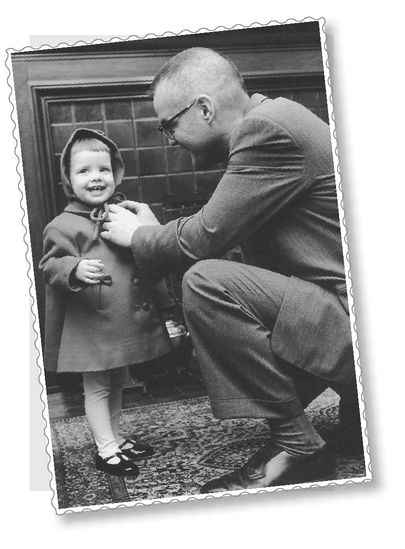

Marilyn and her father, Dr. McCormack

Back then, such operations were primitive and usually didn’t work, but the decision to try gave Dr. McCormack a sense of purpose. In the summer of 1961, he flew to Rochester, New York, to have his first operation. It failed. In the spring of 1962, he flew to Eureka, California, to meet another surgeon, who was then doing experimental work in vasectomy reversals. Dr. and Mrs. McCormack told no friends or loved ones what they were trying to accomplish. They explained the out-of-town trips as business meetings.

That 1962 operation seemed to work. The couple waited. That summer, Mrs. McCormack became pregnant.

On April 8, 1963, Marilyn was born.

M

arilyn knows well that she was brought into this world to deliver life to a family still grieving death. From childhood on, she saw this as both a responsibility and a gift. And today, as she looks back, she realizes that the gripping circumstances of her birth helped shape her friendships.

arilyn knows well that she was brought into this world to deliver life to a family still grieving death. From childhood on, she saw this as both a responsibility and a gift. And today, as she looks back, she realizes that the gripping circumstances of her birth helped shape her friendships.

It’s understandable that she often thought of herself as an outsider among the Ames girls. When the others were making questionable decisions—about drinking or having secret parties or ignoring schoolwork—she’d sometimes feel too guilty to participate. She never wanted to disappoint her parents or lie to them. How could she? Before she was born, they had wanted her so badly. She’d have to be an ingrate not to honor that.

At times, that made her seem prissy and subdued. A prude in a pageboy haircut. Some of the other girls would roll their eyes when they talked about her. But she stood firm. “I feel lucky to be alive,” she’d tell herself, “and so I need to take life seriously.”

In the diary she kept all through junior high and high school, she sometimes wondered why she was even part of that group of eleven girls. Some of them were too wild. Their behavior with boys and alcohol didn’t always feel right to her. On too many weekends, the Ames girls were hanging out with guys who seemed to have nothing intelligent to say. She got tired of sitting around, listening to boys brag about drinking too much and throwing up; they called it “the Technicolor yawn,” and thought they were so clever. Marilyn briefly dated one boy who set out to prove how macho he was by cutting the seat belts out of his car. He figured girls were turned on by guys who lived dangerously. Actually, Marilyn thought he was cute for sure, but after too many remarks like that, she knew he was a loser. And that made her question her friendships, too: Why did some of the other Ames girls seem so happy hanging out with dim bulbs like that?

Marilyn also was unhappy that the other Ames girls weren’t being inclusive socially. Other girls at school didn’t like it. She’d vent about the Ames girls’ cliquishness in her diary. “I hate being identified with them!” she wrote at one point.

And yet at the same time, she saw something she admired in each of the girls—an open heart or a sense of playfulness or a contagious urge for adventure. She had an ability to notice people’s positive traits. In that respect she was like her dad, who would say he could find the good in anyone. And so she remained with the group, even though at times she’d hold herself off to the side.

It’s not surprising that she felt closest to Jane Gradwohl, who in her own way, as the only Jewish girl in the group, knew what it felt like to be a bit of an outsider. Jane and Marilyn were part of the eleven, but also in their own two-person orbit. They had met as ten-year-olds in a local theater production of

Hansel and Gretel

. Jane was cast as Gretel, and Marilyn was jealous and annoyed. She got over it.

Hansel and Gretel

. Jane was cast as Gretel, and Marilyn was jealous and annoyed. She got over it.

By eighth grade, Marilyn and Jane were confidants. They were a good match, too: Both were a little slower than the other girls socially, a little nerdier, more academic. Like others among the Ames girls, they came from families where matters of culture and the arts were regular dinner-table conversation. ( Jane’s father, the anthropology professor, got his Ph.D. from Harvard; her mom was a social worker.) So Marilyn and Jane, especially, felt comfortable talking to each other about classical music or ancient Greek architecture or silent movies. They sometimes felt like black-and-white throwbacks in a town teeming with Technicolor yawns.

As their friendship blossomed, they both felt the need to mark their connection. Early in high school, they bought each other a matching star sapphire necklace. One necklace was engraved: “MM Love, JG.” The other read: “JG Love, MM.” They were always trading notes in which they gushed about their feelings for each other. Looking back at it now, they find the mushiness almost embarrassing. Jane has a scrapbook from high school, and glued into it is a Hallmark card Marilyn had picked out for her. Hallmark had written: “Our relationship is so strong because we are completely truthful with each other in every word and thought, and because we trust each other as equals in every aspect of life.”

They had their own playlist of background music by Cat Stevens, Dan Fogelberg, Hall and Oates, Bread—each song reminding them of a shared laugh or an unrequited crush.

Marilyn told Jane about the first boy to kiss her on her ear and her neck. “It felt so warm and tingly,” she explained. “I could fall asleep holding him. I really could.” Later, when the boy told her, “I don’t like you sexually, but we can be friends,” she cried to Jane.

Jane and Marilyn, t hen and now

There were times when the phone rang and Marilyn’s heart would jump; maybe it was the boy she was hoping to hear from. Invariably it turned out to be Jane on the other end, but Marilyn’s disappointment lasted just a moment before she’d perk up, because hey, it was Jane.

The trust between them was total. Well, almost total. In one of Marilyn’s diary entries junior year, after she had scribbled on and on about how “I just can’t figure out guys,” she suddenly added an aside: “Jane, you’re probably reading this. Let me tell you. I DON’T GET ALL THE GUYS! Believe me! They don’t like me more than you!”

Marilyn confided in Jane about Billy, the brother she never knew, but she didn’t talk much about him to the other girls. A part of her felt uncomfortable with the topic. She remembered what happened one day in elementary school. There had been a girl outside their group who knew the whole story of the car accident and the meaning of the pregnancy that followed. One day, the girl got angry at Marilyn for reasons no one can recall, and blurted out: “I wish your brother had never died, because if he were alive, then you wouldn’t be here!”

Marilyn’s father was the sort of man who could explain what made kids say such things and why they needed to be forgiven for it. He was pediatrician to several of the girls in Marilyn’s group, and he served as a wise counselor to them. “When I was a kid, he was the smartest person I had ever met,” says Jane, “just a total renaissance man.”

When Karla, Jane, Jenny and Karen were newborns, making their first office visits to Dr. McCormack, he talked about how mothers often held babies as if they were delicate objects. Then they would hand their babies over to Dr. McCormack, who flopped the girls from back to front, front to back, as if they were pancakes on the griddle. “Don’t worry,” he said. “It’s fine. They’re not as fragile as you think.” Some mothers were startled, but also relieved by his words. He enjoyed dispensing advice any way he could. Jenny’s mother was taken with the signs he’d post in his examining rooms. “Ant poison is dangerous,” read one. “Better to have ants than poisoned children.” She thought of Dr. McCormack one day when she discovered Jenny’s brother had eaten a cracker with ants on it.

The girls went to Dr. McCormack all through their childhoods, and they have sweet memories of checkups with him. Karen appreciated the time he told her mother that kids needn’t eat all the food on their plates. Dr. McCormack was amused by the clean-plate-club fixation of parents in the 1960s. “Relax,” he told Karen’s mom. “Most kids end up getting the proper nutrition to stay healthy. Their bodies just know what they need. Offer them three square meals a day, but you don’t have to force-feed them.” When Karla went to see Dr. McCormack, her mother would marvel at how he never seemed rushed. He calmly answered every question. It was as if Karla were the only patient he’d see all day.

He also made a point of being honest. In those days, many doctors believed that if they didn’t mention or acknowledge pain, kids wouldn’t feel it or focus on it. But Dr. McCormack gave it to kids straight: “This shot is going to hurt.” It was refreshing to find an adult who cared enough not to sugarcoat things and talk down to children.

As a kid, Jane loved to play doctor. But unlike girls today, she never thought to give herself the role of the doctor. Instead, she’d always assign herself the part of “Dr. McCormack’s nurse.” She spent countless hours in her fantasy world of a pediatrician’s office, saying things like, “Yes, Dr. McCormack, I’ll take the baby’s temperature for you.”

Some of the girls understood that Dr. McCormack was more than just a neighborhood pediatrician, but except for Jane, most didn’t know the full extent of his accomplishments. In the 1960s, he had invented a respirator that helped premature babies with underdeveloped lungs survive. Later, he invented a warming blanket used to transport sick infants between hospitals.

He was way ahead of his time on social issues, too. He passionately advocated the idea of bringing sex education into Iowa school districts and even into preschools. He felt that kids at the youngest ages should be given information about their bodies and their feelings for the opposite sex. “Don’t teach children to feel shame over their genitalia,” he’d say, “or they’ll harbor that shame as they grow older.” He used words that made Iowans blush, but even those who disagreed with him, and there were many, would say they respected his passion. (The Ames girls’ parents tended to be pretty enlightened and never took issue with him.)

Dr. McCormack was described by others as a “people collector,” because he was so engaged in learning about people, asking them to share the details of their lives. He looked for what was special in everyone, including Marilyn’s friends. He’d ask for their opinions about the hostages in Iran or about feminism, and he’d look at them like their answers really mattered to him. He also was good at offering advice that made the girls think. “When you grow up and have kids of your own,” he’d say, “always try to treat them a couple of years older than they are. They’ll rise to the occasion.” Marilyn once had a party and Diana decided to smoke a cigar. No one had told her not to inhale, and soon enough, she was wheezing and sick to her stomach. Marilyn ran up to her parents’ bedroom and got her dad, who grabbed his stethoscope and helped Diana through it. Whether Marilyn’s friends spent too much time in the sun or had too much to drink or had questions about menstruation—whatever—Marilyn’s dad was someone to turn to, and he was there for them without being condescending or judgmental.

Maybe that’s why Marilyn, of all the Ames girls, was often the most willing to confess her sins to her parents. Her father just seemed able to put things in perspective. Once, during a Christmas vacation, Marilyn’s parents weren’t home and Marilyn had some of the girls over. Boys came, too, and soon it was a full-fledged party, with drinking and making out and too many kids coming and going. When it was over, Marilyn cleaned up perfectly. She made sure the Christmas tree and decorations were exactly right. The place was spotless. And that’s when she noticed: There was a large ugly crack in the plate-glass window of the family room.

Other books

Ten Little Bloodhounds by Virginia Lanier

Occasion of Revenge by Marcia Talley

Rite of Exile: The Silent Tempest, Book 1 by E. J. Godwin

Virginia Hamilton by Anthony Burns: The Defeat, Triumph of a Fugitive Slave

Resurrection by Barker,Ashe

Dolled Up for Murder by Jane K. Cleland

Targets Entangled by Layne, Kennedy

Gracie by Suzanne Weyn

Midnight Fire by Lisa Marie Rice