The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (83 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

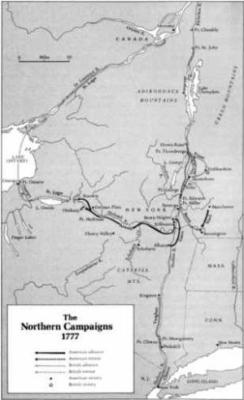

Flight approached rout in the next week. Burgoyne, who sailed up the lake to Skenesboro, almost caught the bateaux that had carried the sick from Ticonderoga. Ashore the British took Fort Anne, but no army could keep up with St. Clair, who reached Fort Edward on the Hudson on July 12. The worst of the campaign -- though not the fighting -- was now over for the Americans. For the British it was really just beginning.

Burgoyne's problem in July was how to move from Skenesboro near the head of Champlain to Fort Edward on the Hudson. The best method, one which Burgoyne himself had approved while still in England, was to return to Ticonderoga, shift his boats into Lake George, and sail to the head of that lake. There he would find Fort George, a convenient base from which to follow a road already cut to the Hudson, a distance of about ten miles. Sensible though this plan was, Burgoyne discarded it; his reasons cannot be fathomed. Two years after the campaign he offered an explanation of sorts: the morale of his army concerned him, and morale would have been very much impaired by "a retrograde motion." Besides, had he pulled back, his enemy would have remained at Fort George, as their retreat could not have been cut off. The only way in that situation to dislodge the Americans would have been to

____________________

22 | John Burgoyne, |

23 | Hadden's Journal |

"open trenches" -- besiege them, in other words -- an operation which would have delayed his advance even more. Then, too, marching overland from Fort Anne to Fort Edward "improved" the troops in "wood service," a justification Burgoyne apparently presented with a straight face.

24

Whether or not the troops were "improved" in "wood service," they got their bellies full of it between Skenesboro and Fort Edward. Their way ran along Wood Creek, an aptly named stream, which twisted erratically down a valley covered with large hemlocks and even larger pines. The road crossed the stream in no fewer than forty places, many of them deep ravines spanned by long bridges. General Schuyler knew this country and saw his opportunity.

25

Burgoyne did not strike out from Skenesboro immediately. He was short of oxen and horses to draw his wagons, and he was not traveling light. He had brought his mistress; and Baron von Riedesel had allowed his wife and three daughters to accompany him. Nor had the officers of lesser rank stripped down excess baggage: a good deal of unessential weight was being carried. Part of this weight, of course, was in servants and the inevitable camp followers.

When the army did resume its advance, it faced formidable obstacles -the trees across the road, the ruins of bridges, boulders in Wood Creek, and rough ground made rougher by the Americans. There was, However, no American opposition, Schuyler having withdrawn "deliberately," as a British officer remarked, and with his 4500 intact. By August 3 Schuyler had reached Stillwater on the Hudson, twelve miles below Saratoga. And from there he moved another twelve miles, close to the mouth of the Mohawk River. On August 4 orders went out: Gates was to replace Schuyler as commander of the Northern Department. The army, its numbers dwindling as the soldiers indulged in the American propensity to desert, rejoiced in the change. No one knew it, but the days of retreat in the face of Burgoyne's expedition were over.

26

Just before the change in the American command, Burgoyne's advance party made its way on July 30 into Fort Edward. His men were not cheered by the ruins of the fort, though they had at last reached the Hudson. The drive from Skenesboro had consumed three weeks and exhausted them all, their animals, and their supplies.

Confronted by shortages of all sorts, except ammunition, Burgoyne

____________________

24 | Burgoyne, |

25 | Bradford, ed., "Napier's Journal", |

26 | Hadden's Journal |

listened to Riedesel's proposal to send an expedition as far east as the Connecticut River to forage for cattle and horses. Riedesel recommended that a large party be sent out in the expectation that it would return with meat for the troops and mounts for his horseless Brunswick dragoons. These Germans had found the march to Fort Edward a torture. Burgoyne probably did not feel much sympathy for the Brunswickers but he needed food, and he knew that bringing it from Ticonderoga would be almost impossible.

27

Lt. Colonel Baum was detached to lead the raid and given some 600 soldiers. Baum, who spoke no English, was instructed to enlist the support of the citizens he encountered. Burgoyne's orders contained references to Baum's expedition as "secret," and it was given a German band to, in the historian Christopher Ward's sardonic phrase, "help preserve its secrecy." This expedition departed on August 11. On the 15th near Bennington Baum's party was surrounded by a force twice its size, led by Brig. General John Stark, and virtually destroyed. Later a relief party, which had been dispatched on August 14, was also chewed up in a day by Stark's militia.

28

News of this "disaster," as one of Burgoyne's officers called it, reached the main army on the night of August 17. Burgoyne reacted with uncharacteristic speed and had the troops instructed at 2:00 A.M. to be "in readiness to turn out at a moment's warning." Not quite two weeks later, more unhappy news arrived. Lt. Colonel Barry St. Leger had given up the siege of Fort Stanwix. Commanders who had been feeling lonely now began to sense just how isolated the expedition was.

29

The British were not isolated, whatever else they felt about their situation. But they were at a critical juncture and Burgoyne knew it. He had about a month's supply of food and his troops were in fairly good shape. They were far from the magazine on Lake Champlain, However, and with rather short supplies and lacking winter quarters they could not remain where they were -- on the east side of the Hudson far from Champlain and not close to Albany. Burgoyne might have pulled back to Ticonderoga, but he was averse to withdrawal, which everyone would have considered an admission of defeat. So he boldly and bravely decided to continue his drive to Albany.

30

____________________

27 | Ward, I, 421-22. |

28 | Ibid., |

29 | Hadden's Journal |

30 | Ward, II, 501. |

Burgoyne decided at the same time that he must cross the Hudson to the west side. He might have remained on the east side and marched virtually unopposed to a point across the river from Albany. Crossing the Hudson at Albany would have been immensely difficult, However, for not only was the river wider there but the Americans would have concentrated their forces to oppose his crossing. Therefore he threw a bridge of bateaux across to Saratoga and on September 13 began sending his troops to the west bank. Two days later his army was safely over.

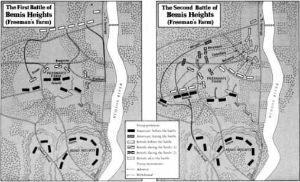

The American enemy had not been inactive while this movement took place. Gates had reached the army at Albany almost four weeks before, on August 19, and he had moved his forces northward. Gates's command had grown in this period to 6000 or 7000 men. The day before Burgoyne began to put his troops over to the west side, Gates undertook to fortify Bemis Heights, three miles north of Stillwater.

This stretch of the Hudson saw the river forced through a narrow defile by high bluffs 200 to 300 feet above its surface. Bemis Heights, around 200 feet above the water, was separated from nearby slopes by ravines cut by creeks which flowed into the Hudson. Much of the ground from the river to the slopes was covered by thick stands of oak, pine, and maple.

Gates's brilliant subordinate, Benedict Arnold, may have chosen Bemis Heights as the position for defense. Arnold and Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, the Polish engineer, drew the lines of fortification, which extended from Bemis's Tavern near the river up the bluff to the top of the Heights. There a three-sided breastworks of earth and logs, each side about three-fourths of a mile in length, was put up. The south side, presumably the farthest from the advancing British, was left unprotected, though a ravine there afforded some protection. At the midpoint of each side of the breastworks the Americans dug a redoubt where they emplaced artillery. In most respects the Americans had built wisely, but they had left virtually unoccupied a high slope less than a mile to the west. Should the British drag artillery to this height they would command Bemis Heights.

31

Burgoyne had crossed the Hudson about ten miles above Bemis Heights and spent the next two days crawling southward groping for his enemy. On that march with three loose columns, Riedesel on the left along the river, Brig. General James Hamilton in the center on the road (hardly more than wagon ruts), and Fraser on the right to

____________________

31 | Ibid., |